The Muse by Jessie Burton

Ecco

Pp. 390

The parallel stories in this

novel lead the reader to wonder just exactly who is whose muse? It begins in

London in 1967 when aspiring Caribbean writer, Odelle Bastien, finds employment

at an art gallery, falls under the tutelage of the enigmatic co-director Marjorie

Quick, and is seduced by the charms of Lawrie Scott who appears to have a

valuable painting to assess. Interwoven chapters focus on the story of Olive

Schloss, daughter of Harold and Sarah, who becomes involved with wannabe

artist, Isaac Robles, while in Arazuelo in Spain, 1936. Isaac also dreams of

being a revolutionary much to the chagrin of his half-sister Teresa who works

as a housekeeper for the Schloss family and just wants to avoid trouble.

Of course the

names and dates recall the Windrush generation, the Spanish Civil War and the

treatment of Jews leading up to WWII. Meanwhile, there are themes of unrequited

love, parent-child relationships, and the difficulties of creative women

wanting their art to be taken seriously. Lots of people are manipulating each

other and hiding secrets in order to score points. It all becomes somewhat

messy and incoherent as the author tries to pack too much detail into her story

(there is a bibliography at the back to prove she has done her research) and it

doesn’t tie together very well. Although the descriptive passages are fantastically

evocative, the characters are all one-dimensional and the story itself is

unengaging and predictable. In both stories

there is a sense of dislocation, privilege and misunderstanding, the notion of

shared responsibility and mutual history, and overwhelmingly, the dangerous man

trope.

|

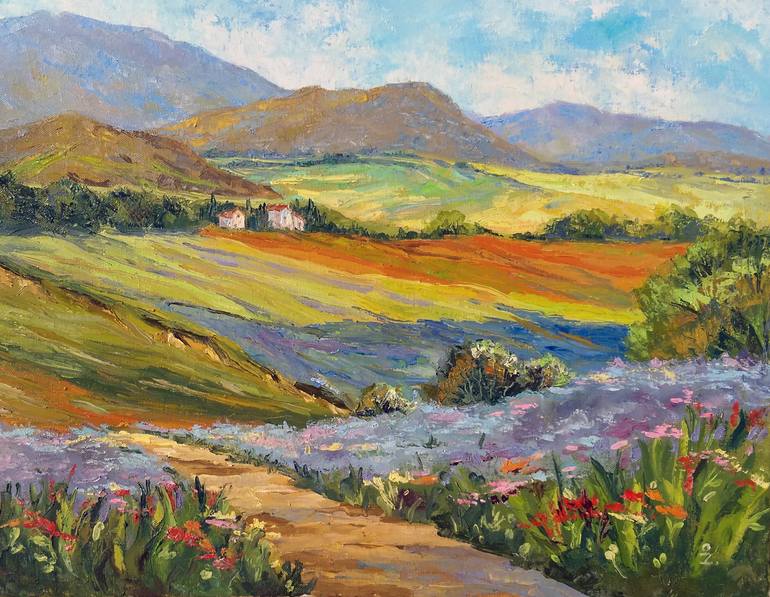

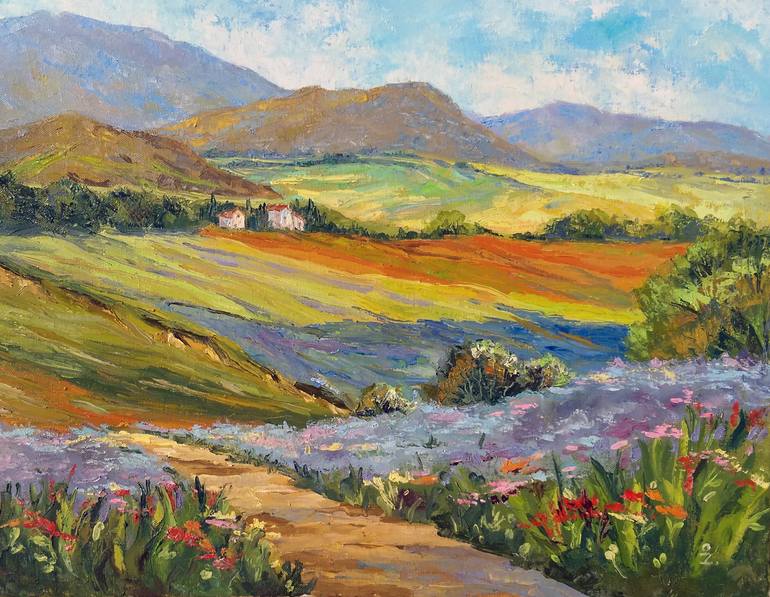

| Spanish landscape by Olga Zaitseva |

Olive paints pictures

and asks Isaac to take the credit for it, aware that her art-dealing father

won’t admire it if he knows the true artist. When Isaac protests she should own

the paintings, she rejoinders, “Do you know how many artists my father sells?

Twenty-six last time I counted. Do you know how many of them are women, Isaac?

None. Not one. Women can’t do it, you

see. They haven’t got the vision, although

last time I checked they had eyes, and hands, and hearts and souls. I’d have

lost before I even had a chance.” Of course, this is the provenance of the

painting that falls into Lawrie’s hands – there is no mystery to this novel.

Olive argues, “They believe it’s Isaac’s painting, and that’s all that matters

isn’t it? What people believe. It doesn’t matter what’s the truth; what people

believe becomes the truth.”

The

attempt at post modernism and attitudes to post-truth are as lazy as the themes

of stolen art in Nazi times and the blatant dramatic irony of the impending

Kristallnacht. Other descriptive aspects of the prose, however, are a highlight

of the novel making the evocative images of Arazuelo in July seem like a

painting. “From the hills came the dull music of bells as the goats overtook

these smaller sounds descending the scree through the gauze of heat. Bees,

drowsing on the fat flower heads, farmers’ voices calling, birdsong arpeggios

spritzing from trees. A summer’s day will make so many sounds, when you

yourself remain completely silent.” The novel is competent but the craftsmanship

is on clear display.