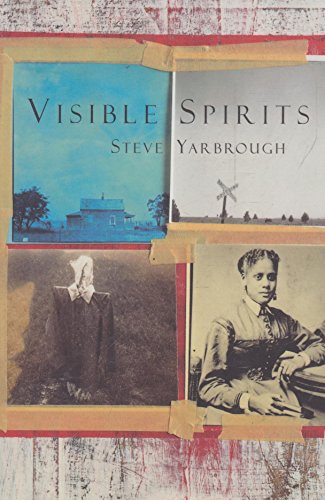

Visible Spirits by Steve

Yarbrough

(Picador)

Pp. 273

In this novel of post-reconstruction

Mississippi (Loring, 1902), although slavery is illegal, racism is rife and respected

by many, blacks and whites alike. Leighton is mayor and runs the local

newspaper, using it as a platform for moderation; his younger brother Tandy

returns after losing his money gambling and whoring in New Orleans. The two

brothers have opposing outlooks, especially over the issue of the black postmistress,

Loda, in this bleak view of passion, politics and race.

Tandy is trouble, and not in an

attractive romantic way. He wants to stir things up in his old home town, and

agitates Sarah, Leighton’s wife, with whom he clearly had a previous

relationship. He is the embodiment of white male entitlement. “Until now, he’d

never done any real work, because he’d always felt he was destined for

something bigger. Of that he was no longer certain, but he could see one thing

for sure: work was work, and he’d been wise to avoid it as long as he could.” Tandy

and Leighton inherited half of the proceeds of the farm each when their father

died and they sold it, Tandy to gamble it away and Leighton to invest it. Now

Tandy wants to reverse fate, but without any exertion on his part.

Tandy claims that Loda encouraged

a black man, Blueford, to behave insolently to him, and requests her dismissal

from the post office, as he covets her job. After he brutalises Blueford, Loda

tenders her resignation to avoid further conflict, but Theodore Roosevelt's

administration decides to make a civil rights stand by refusing to accept it.

In the escalating dispute,

Leighton becomes a pariah for siding with Loda, and Sarah despises him for

putting her into a controversial position. She doesn’t share his views but

knows that she is judged for them, asking, “What am I but an extension of my

husband?” One of the strengths of the novel is the multiple viewpoints;

different perspectives are raised and the reader is asked to take sides. We may

not agree with Sarah’s racial stance, but we may react more sympathetically to

her gender impotence.

Tandy continues to incite unrest

with half-truths, slander, misinformation and downright lies. Preying on the

people’s need for nostalgia and heroic pasts, he twists terrible events to suit

his own ends, making his deeds fit a principle that he never held. “He’d work

his way backwards from the action to the reason, discarding all the garbage in

between.” Having lit the powder keg, he stands back and watches the spark

ignite.

Many reviewers have criticised

the novel for its lack of a definitive ending, suggesting that the author never

really resolves the crisis, or creates a lasting peace. Surely, however, this

perfectly represents contemporary social politics, where outsiders guide communities

to make snap decisions with lasting consequences, and then hold up their hands

and walk away. Who can really claim to be blameless? This is a disturbingly

bleak novel with an elegant style and a deceptively straight-forward plot.

No comments:

Post a Comment