Di

Morrissey sets place extremely well. In her dozens of novels, the scenery and

landscape are immediate and infinitely better drawn than her characters or

plotlines. The Opal Desert is,

unsurprisingly, set in Lightning Ridge, Broken Hill, Opal Lake, and White

Cliffs, where most people are exceptionally friendly and we learn about the

precious stones and the community who mine them. The three women around whom

Morrissey tells her tale, Kerrie, Shirley and Anna, are all fairly predictable

stereotypes who overcome their personal obstacles in life-affirming ways, which

may not be realistic, but are heart-warming.

Kerrie

is our main character who realises, after her sculptor husband dies, how much

he absorbed her life into his, and that she doesn’t get on with his children.

For spurious reasons (a recommendation from a friend’s lawyer), she decides to

head to opal country to find herself and reconnect with her own artistic side. She

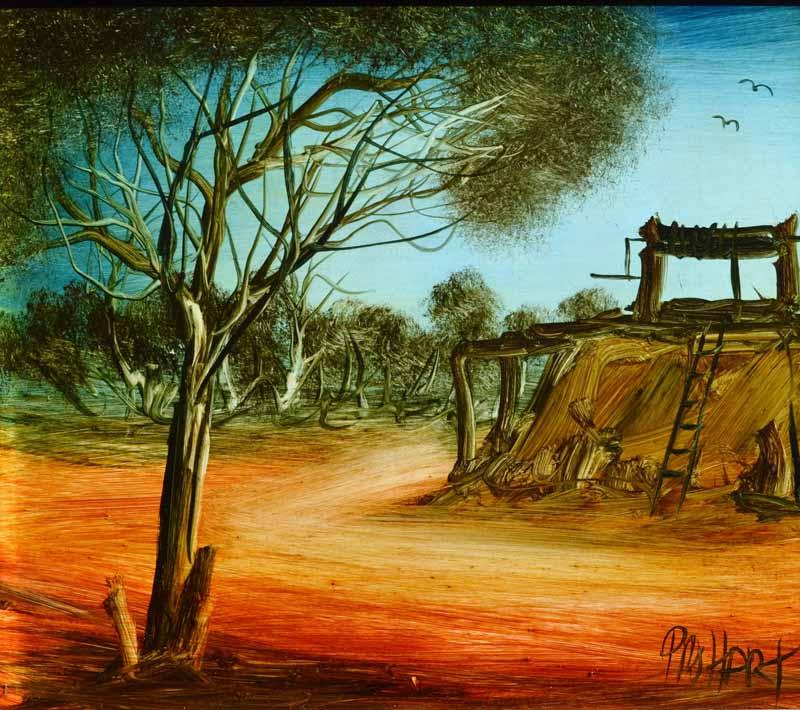

encounters a land rich with visual treasures, art galleries and bush art,

inspired by painters such as Pro Hart and Jack Absalom. She admires the light

and bright colours.

|

| The Windlass by Kevin Charles (Pro) Hart |

Naturally,

Kerrie also learns about the flash of opals – white, fire, black – and their

addictive appeal. She appreciates the act of opal mining because it is

“relatively small-time… unlikely to ever become a huge and invasive industry

like gas, oil and iron ore.” As well as the beautiful stones, she learns,

“Sometimes miners dig up fossils of shells and sea creatures, even dinosaurs.”

She is told that, “Australia is the only place in the world which has opalised

animal fossils. They’re not only beautiful, but important scientifically.”

There is some friction between those who want to collect the fossils for their

historical value, and those who want to break them up and create unique pieces

of jewellery for sale. This is an interesting aspect of the book and even

non-geologists will appreciate the basic descriptions of which rock formations

lead to which varieties of opals.

Our

next character is Shirley, an elderly woman who lives in a dugout she rarely

leaves (due to a mysterious past event), but she socialises with everyone.

“Shirley’s just Shirley, but she knows a bit about everything. She’s our local

historian, sort of. Lovely, lovely lady.” Shirley decides to record the stories

of the old miners so they might pay testament to a way of life that was fast

disappearing. “The mantle of keeper of the stories, the one who held remnants

of a life that might otherwise be forgotten, settled gently and easily on

Shirley’s shoulders.” Di Morrissey’s evocation of time and place make her a

type of archivist too.

People

who mine (and live underground) are often a little odd; they live on the

fringes and have personal reasons for being there. One character states, “I

like going out to the opal fields. Special people out there, too. There’re some

gems, some oddballs, some creative types and those with opal fever. It’s a

place that affects everyone. There are friendly people, and most don’t ask

questions, but there are also shady characters and blatant sexism. When the

young woman, Anna, is introduced, she has justifiable concerns about the

tactile and intrusive nature of some men she encounters. Others become

paranoid, afraid of gangs coming to steal their stones. “It’s not always

sunshine and glittering opals… the dark underbelly of the opal fields… murders,

mystery, ratters and ratbags.”

Beneath

the rose-tinted idealism, lies hidden bias and unconscious racism. Young

Shirley tells her partner, Stefan, “Our history comes from the continent

itself, the landscape, and the opportunities for people to carve their own

paths, using their skills and knowledge.” This becomes complicated when she ignores

Aboriginal history, “It must be stultifying being lumbered with thousands of

years of history. Here, in Australia, you have the opportunity to be creative

and original without the burden of the past. This country is like a clean

slate.” Clearly this was written before the words ‘young and free’ in the

Australian national anthem were changed to ‘one and free’ in an attempt to

‘foster a spirit of unity’, acknowledge ‘the fact that we have the oldest

continuous civilisation on the planet right here with First Nations people’ and

‘honouring the foundations upon which our

nation has been built and the aspirations we share for the future.’

No comments:

Post a Comment