In Memoriam by Alice Winn

Viking (2023)

Pp. 375

In Memoriam

is reminiscent of Atonement and Testament of

Youth as it covers the doomed generation of young men who went to war and

never returned, either because they were killed or changed irrevocably. Also

discernible are elements of Pat Barker’s Ghost Road novel, wherein, like

the WWI poetry we all studied in school with the benefit of hindsight and

distance, we can plot the way innocence, ideology and excitement turned to

disgust, betrayal, anger and frustration. Our characters transform from

schoolboys worried about their families and duty to wounded and embittered

cynics whose promise was destroyed by a class system into which they had no

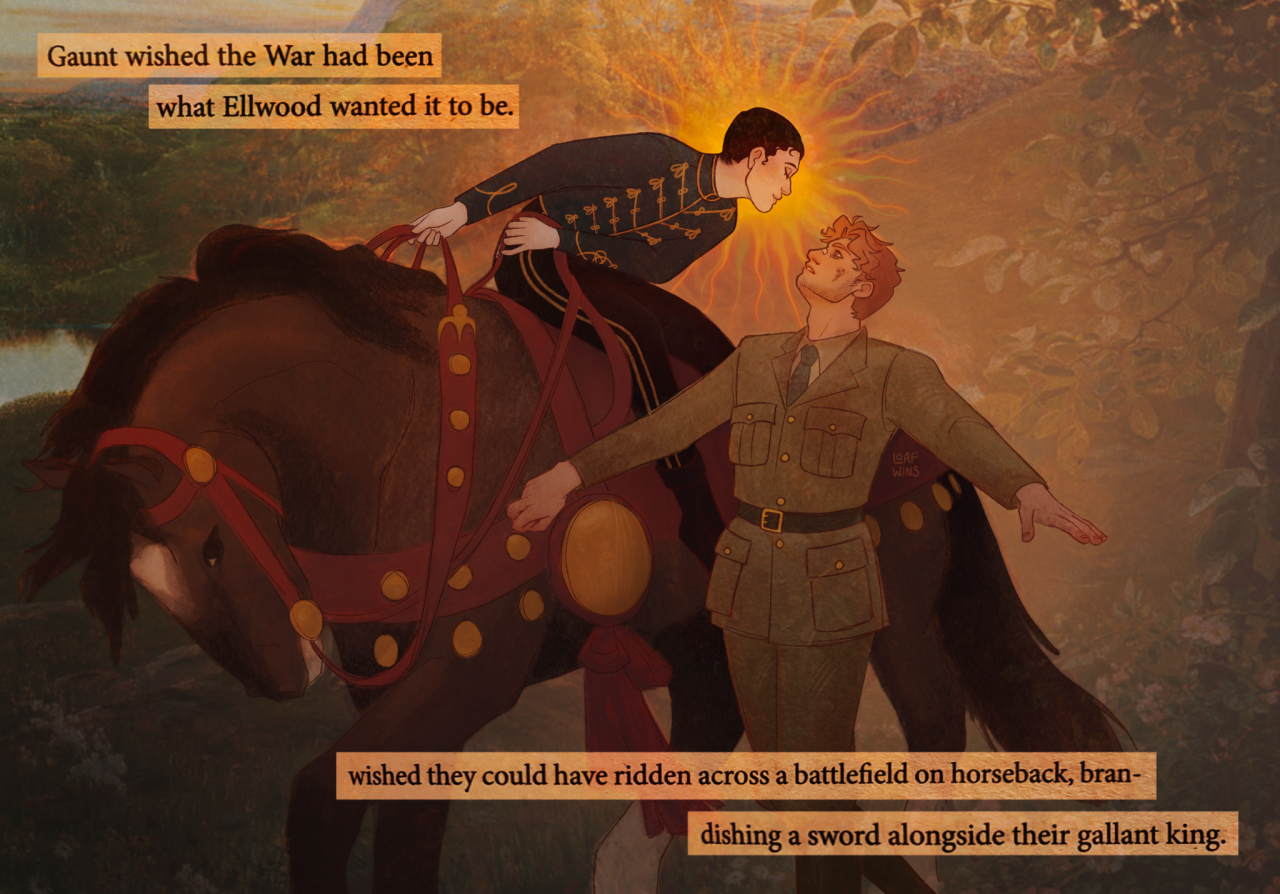

input. And at its heart it is a love story between Gaunt and Ellwood, two young

men coming of age in a time when homosexuality was still illegal.

Winn writes in linear style, with sharp, clear

sentences, avoiding excessive adjectives, but with a profoundly moving poetry.

Beginning in a public school, the use of last names and lack of sentiment

suggests a world of staunch young classically educated men with notions of

empire and glory. Word of the deaths begins to reach the schoolboys back in

England – those who hadn’t lied about their age to sign up – and are reported

in their school newspaper, The Preshutian. The reports begin cheerily:

every man killed dies ‘gallantly in battle’ with a smile and a quip, proud to serve

his country. Later, after The Somme, there are just lists of the dead, and the

commentary becomes much more sombre. “After the calamity of the past four

years, we look to the future with hope, determined to make Cyril’s sacrifice,

and that of a thousand others, count towards a lasting harmony in Europe. Let

us, like the soldiers of Waterloo, have our century of peace and prosperity,

for we have paid for it in blood.”

The irony of hindsight brings poignancy to scenes and

situations. “Loos hung over them, a word he felt sure would someday have black

meaning, but now was only a whisper of dread in his stomach.” There are echoes of

Blackadder Goes Forth in the trench talk, where there is resentment of

the upper class automatically being made officers and promoted to captains,

having authority over men much older and more experienced than them. One

character exclaims bitterly, “My school didn’t train me to rule an empire”, and

when he is told they are more realistically losing an empire, another character

interjects, “What rot! Losing the empire – look at how the Gurkhas fight! They

love England just as much as we do, anyone can see that.” Meanwhile the men are

falling without class distinction in a horrifically mundane manner. “At nine,

they went over the top. West’s head was shot off before they had gone two feet.

Elwood paused to look at his brains. Pritchard had always said he didn’t have

any, but there they were, grey and throbbing and clotted with blood.”

Poetry is present in the straightforward descriptions

of the terrain, “The rain came down in ropes. They climbed quietly out of the

trenches and crawled through the poisonous, corpse-studded No Man’s Land. It

was usually silent, but tonight, the thousands of wounded groaned like a ship

in a storm.” The situation becomes so surreal that there is no equivalent

behaviour. “They did not even run, but plodded to their deaths, like – There

was no comparison. No animal on earth would have suffered it. No creature would

walk so knowingly, so hopelessly into the jaws of death.”

The section set in a prisoner of war camp is almost a

comic diversion. “It’s astonishing how well an English boarding school prepares

one for prison.” All the prisoners are bored, chatty and trying to escape,

while the guards are generally good-natured and long-suffering. “The men spent

their time galloping around the dining hall, antagonising the guards, reading

and rereading Adam Bede, and, most notably, plotting elaborate escapes.”

They are happy to assist each other, as Gaunt notes, “It was much easier to be

brave for your friends than for yourself.”

After years of erotically-charged friendship, Gaunt

and Ellwood finally admit their love for each other. “A sudden, dry bleakness spread

over Gaunt’s heart as he thought of Hercules and Hector, and all the heroes in

myth who found happiness briefly, only for it not to be the end of the story.” Gaunt

and Ellwood are subsequently separated and assume each other’s death, yet love

persists despite all, in a romance like that in The Bronze Horseman by

Paullina Simons. As in The Imitation Game, men who fought for their

country are not accepted there due to their sexuality, so many of them leave

and go to Brazil. “Gaunt thought of the darkling plain, of skating in the

winter, of crunching over frosted grass early in the morning, of bluebell

meadows in spring. There was nothing he wanted more than to spend the rest of

his life on Wiltshire country lanes, Elwood at his side. It was what he had

fought for, what his friends had died for.”

In Memoriam is Alice Winn’s debut novel. It may not be an

original topic, but it is excellently written. She writes captivatingly about

things of which she can have no first-hand experience: life in the trenches,

male sex, and English public schools with a ring of authenticity. I look forward

to her next offering.