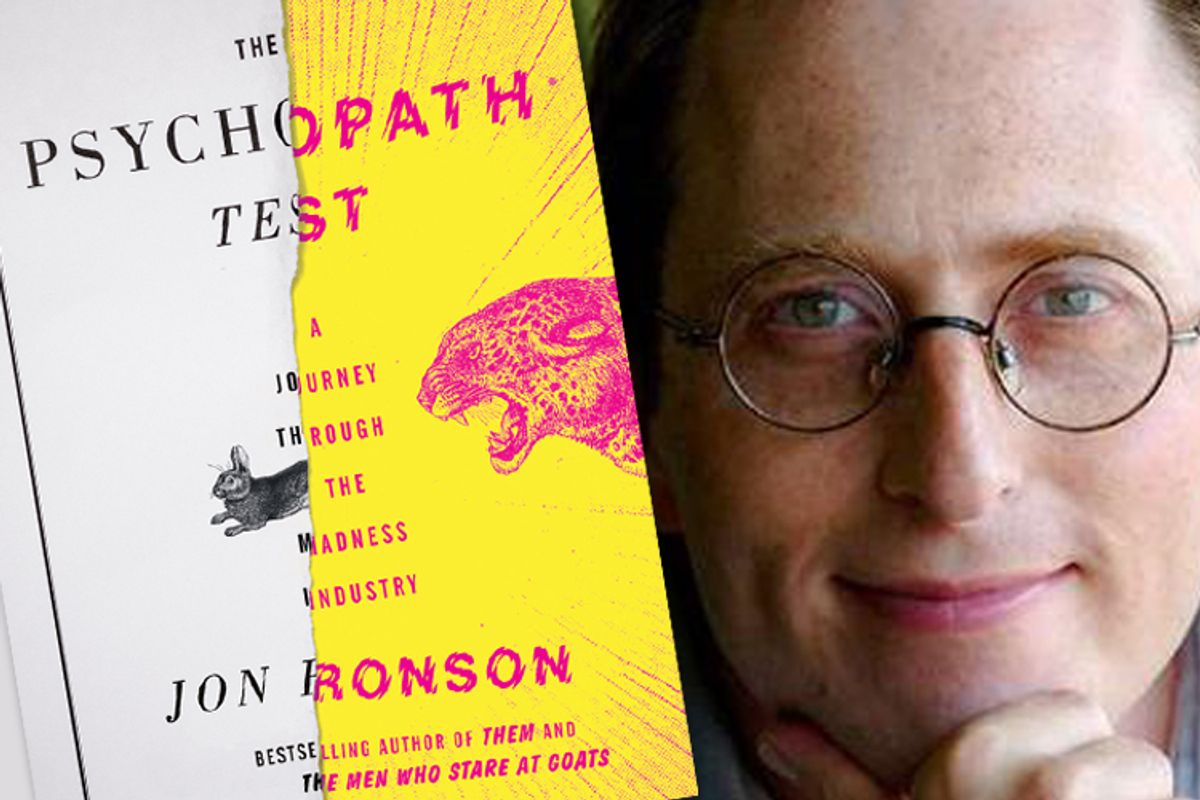

The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry by Jon Ronson

Riverhead Books

Pp. 272

We have a lot of examples in

popular culture of what it looks like to be ‘mad’. The mental health industry

has become increasingly prevalent and topical. Journalist Jon Ronson explored

this phenomenon through a series of interviews and other research methods to

publish this highly accessible study in 2011. While many people now

self-diagnose, due to the availability of tests and checklists, others exhibit

psychopathic behaviour almost undetected, and often end up running companies or

countries.

He begins with the premise that

it can be harder to persuade people you are ‘sane’ than it is to convince them

you are ‘mad’. Ronson is allowed access to one of the most notorious

psychopaths, incarcerated in Broadmoor Clinical Lunatic Asylum, Tony, who is

allowed to read his own medical files and pass them on to Ronson. Tony claims

that he faked madness and now no one believes he is sane when he tries to deny

it. “Tony said faking madness was the easy part, especially when you’re

seventeen and you take drugs and watch a lot of scary movies. You don’t need to

know how authentically crazy people behave. You just plagiarize the character

Dennis Hopper played in the movie Blue

Velvet.”

Often psychopaths can present as

totally charming, which makes it difficult to detect. Ronson says, “The moment

I’d first seen Tony, he had strolled purposefully across the Broadmoor Wellness

Centre in a pin-striped suit, like someone from The Apprentice, his arm outstretched.” (That particular TV

reference is unintentionally relevant). Dressing smartly and being personable

(“Glibness/ Superficial Charm”) is the first indication on the most available

test; the twenty-point Hare Checklist, devised by Canadian psychologist Bob

Hare, “the gold standard for diagnosing psychopaths.” The checklist is included

in the book , so that readers can take it for themselves. Find it here: http://www.clintools.com/victims/resources/assessment/personality/psychopathy_checklist.html

It is common to redefine the psychopathic

traits on the checklist as Leadership Qualities and the crossover can be a very

fine line. In examining ‘lack of remorse or guilt’ and ‘callous/ lack of

empathy’, Ronson highlights CEO Al Dunlap, formerly of Sunbeam. It is evident

that if this book had been published ten years later, Donald Trump and Jeff

Bezos would have been prime case studies. Ronson wonders whether highly driven

and successful people are actually insane, and if what makes psychopaths so

scary – no fear, filter, no conscience – also makes them good executives. Hedge

funds, pension funds and investment banks advise their clients which companies

to invest in, and they rejoice in job cuts and applaud as research facilities,

tech areas and training centres get destroyed. Psychopathic behaviour is on

prominent display on Wall Street.

Mental health disorders are

listed in the DSM (Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), which lists mental disorders. It is

used by clinicians, researchers, psychiatric drug regulation agencies, health

insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, the legal system and

policymakers. Robert Spitzer, who worked on DSM-III

explained that the idea was to list potential new mental disorders and a

checklist of their overt characteristics. “It seemed a foolproof plan. He would

eradicate from psychiatry all that crass sleuthing around the unconscious.

There’d be no more silly polemicizing… Instead it would be like science. Any

psychiatrist could pick up the manual they were creating – DSM-III – and if the patient’s overt symptoms tallied with the

checklist, they’d get the diagnosis.”

DSM-III sold more than

a million copies, mainly to civilians rather than professional psychiatrists. “All

over the western world people began using the checklists to diagnose

themselves. For many of them it was a godsend. Something was categorically

wrong with them and finally their suffering had a name. It was truly a

revolution in psychiatry, and a gold rush for drug companies, who suddenly had

hundreds of new disorders they could invent medications for, millions of new

patients they could treat.” As one psychiatrist Ronson interviewed confirmed, “A

surfeit of checklists, coupled with unscrupulous drug reps is a dreadful

combination.”

Ronson

can’t help but test himself and starts to worry that, as a journalist, he might

meet some of the criteria. One of his interview subjects tells him, “Finding

patterns is how intelligence works. It’s how research works. It’s how

journalism works. The search for patterns.” He also considers that in the very

act of researching and writing this book, he might be contributing to the way

that madness is packaged and presented for entertainment. “I was writing a book

about the madness industry and only just realizing that I was a part of the

industry.” He probably doesn’t think about the paradox too deeply. After all,

that way madness lies.