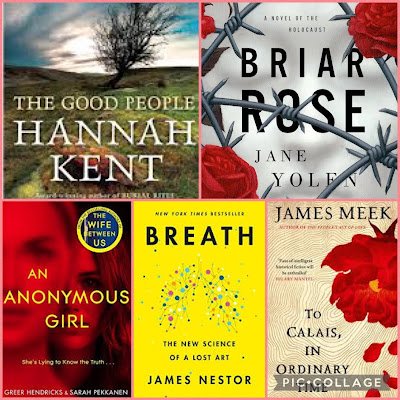

By sheer coincidence it appears that I have read five books in July, and that red features quite prominently in the covers. Here, then, are brief overviews (full reviews to follow later).

5 Books Read in July:

- To Calais in Ordinary Time by James Meek (Canongate) - Mixing elements of The Canterbury Tales and Shakespearean comedy, this story takes place in South-West England in 1348 as a group of bowmen travel through the country from Outen Green in Gloucestershire to Calais to fight the French, while the plague is advancing steadily towards them. As the novel was published in 2019 all the reviewers drew contemporary parallels with Brexit and the existentialist threat of the climate crisis, but anyone now would automatically think of the Covid pandemic. The novel is narrated from three different people’s perspectives, and the voices are clearly different - there is much merit in juxtaposing the courtly language and behaviour of French romance with the idioms and earthy attitudes of the English soldiers, and the novel was unsurprisingly on many newspapers' 'Books of the year' lists.

- An Anonymous Girl by Greer Hendricks & Sarah Pekkanen (Picador) - this is one of those currently fashionable psychological thrillers about women behaving badly. New York psychologist, Dr Shields conducts an experiment on morality and ethics which make-up artist, Jessica wangles her way onto - fraudulently taking the place of the 'real' subject. It soon transpires that all is not as it seems (surprise!) and that everyone is manipulating each other. The two characters are meant to be written individually but they sound exactly the same, apart from one of them refers to 'you' throughout, which soon becomes intensely irritating. We are meant to find the vapid minutiae of their existence fascinating - from how they dress to what they eat - and it won't be long before someone snaps up the rights and makes another tediously glib and glossy film.

- Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art by James Nestor (Riverhead Books) - Every living body breathes, but it turns out that half of us are doing it wrongly. Ancient humans and Eastern mystics knew the correct methods, but modern lifestyles have ignored them leading to multiple health issues including tooth decay, sleep apnoea, anxiety, asthma, and the preponderance of choking. It may be skewed towards anecdotes and storytelling rather than academia and science (think popular American documentary podcast) but there's enough insight to challenge conventional wisdom and make the case for nasal breathing over mouth breathing.

- The Good People by Hannah Kent (Picador) - Set in 1825 in South-West rural Ireland, this novel explores liminal spaces and inexplicable things: “The strange hinges of the world, the thresholds between what was known and all that lay beyond”. In this world many follow the ‘old’ beliefs that children (and adults) could be stolen (swept) by the fairies to be replaced by changelings. It is dripping with pathetic fallacy as the female power (herbs and agricultural lore represented by the Wise Woman) is challenged by that of the male (a priest with punishments and preaching of sin). A great one for book clubs, it gives rise to much discussion, but - as to be expected - things are pretty grim.

- Briar Rose: A Novel of the Holocaust by Jane Yolen (Tor) - Jane Yolen has form for taking mythical legends and fairy stories, and twisting them into contemporary tales with relevance and meaning. In this YA novel of a young woman, Becca, trying to find out more about her grandmother's mysterious past; the castle is a concentration camp; the sleeping beauty is gassed; and the prince's kiss is the breath of life. That's not a spoiler, because all of that is obvious from the title, but Yolen believes it is not the past that makes us who we are, but the way we tell our histories. Every other chapter returns to the recounting of the familiar fairy tale interspersed by Becca's explorations into the unknown; a way in which ritual can help us comprehend the horrific and inexplicable truth.