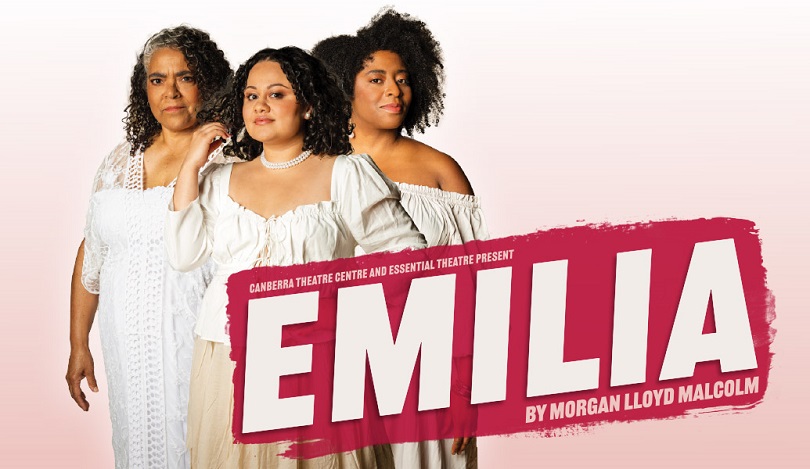

- Emilia - Essential Theatre, The Playhouse, Canberra Theatre Centre: When I read this play, I fell in love with it; it has feminism and Shakespeare intertwined with a glorious delight of language and heritage. It purports that the 17th-century poet Emilia Bassano is not only the 'dark lady' of the sonnets and his sometime lover, but the original writer of many of the works, whose words Shakespeare shamelessly stole to heighten the drama of his plays. Naturally, I was really excited to see this Australian touring version directed by Petra Caliva. Three women play Emilia at different stages of her life - one for her childhood and youth (Manali Datar); one for her young adulthood (Cessalee Stovall); and the third for her as an older woman (Lisa Maza). As each woman tells her story, the other two listen, react, encourage, cajole and reflect from the sidelines. The acting is of a high quality and the dialogue is delivered clearly and with passion. The characters are all played by women with the cowardly, grandiloquent and ultimately pathetic Shakespeare - played by Heidi Arena - getting the best lines and the biggest laughs. The set is minimal, comprising a revolving staircase which represents a multitude of scenes; the costuming brings the modern to the Jacobean (the brightly-colored Converse are a nice touch); and the choreography is eclectic with some snazzy contemporary moves. And yet, it just felt like there was something missing. Perhaps the haranguing and brow-beating tone left no room for nuance or relief so that the final speech, which should be incendiary - "The stakes we have been tied to will not survive if our flames burn bright. And if they try to burn you, may your fire be stronger than theirs so you can burn the whole fucking house down." - felt more like a damp squib, leaving the audience with nowhere to go and no way to react.

- The Tempest - Sydney Theatre Company, Roslyn Packer Theatre: I love the way certain directors interpret Shakespeare to suit their own ends - and why not? In this version of The Tempest (directed by Kip Williams), however, the attempt to force it to fit the 'they stole it from us' colonialist narrative, means Caliban has been made into the good guy by excising all references to his brutal rape of Miranda, Prospero's daughter. Rather than Prospero enslaving him due to fear of his bestial physicality, it becomes purely a white-man-subjugates-a-black-man narrative, and while the white man (Richard Roxburgh) and the black man (Guy Simon) in question are exquisite in their roles, and deliver the bard's blistering words with passionate sincerity, it removes much-needed nuance from the original drama. The set of a big central rock (Uluru anyone?) is inspired as it provides levels, hiding places and dramatic hierarchy, and the lighting effects are spectacular. The rest of the cast are all perfectly cast - Peter Carroll is a waspish and world-weary Ariel; Claude Scott-Mitchell as Miranda gets to speak some of Juliet and Jessica's lines (Shakespeare's other works have been plundered for their poetry), which she does with affecting flair; Susie Youssef is an unexpected boorish delight as Trinculo. Of course, some critics have taken issue with the gender-blind casting, but if they are concerned with straying from 'traditional' portrayals, I would have thought that would be the least of their worries.

- The Importance of Being Earnest - ACT Hub, ACT Hub: Determined to be different, Jarrad West's direction is more cabaret than theatre, including bursts of song (Louiza Blomfield does a lot of heavy lifting as the chanteuse) and outstandingly vibrant costumes designed by Fiona Leach - Lainie Hart as a stylish Lady Braknell presents as a steam-punk-ringleader. Many of the lines have been cut (including the one about never travelling without one's diary so as to always have something sensational to read on the train) and characters' roles trimmed down; Miss Prism (Victoria Dixon in a seething passive-aggressive turn heightened by inebriation) really only serves to be hoodwinked by Cecily (Holly Ross in a wheedling doll-like performance) and for the famous misplaced handbag denouement. The setting is the Bunburry Club, and we are part of the action, with scenes taking place at tables often after audience members have been asked to move to make way for the performers. There is a lot of food and slapstick comedy involved in eating - Cecily and Gwendoline (Shae Kelly making a deliberate mockery of affectation) have a food fight over cake, and Steph Roberts delights in the gluttonous Algernon Moncrieff as she stuffs her face with muffins and refuses to take anything seriously. Joel Horwood has perhaps the hardest role of all as he plays the straight man, Jack Worthing, and with the delightfully gender-blind casting, this is no mean feat. Painting with such broad and colourful strokes, many of the British class nuances are missed but that doesn't seem to matter in this riotous production, which is more of a madcap comedy than a comedy of manners.

- Amadeus - Sydney Opera House, Red Line Productions and The Metropolitan Orchestra, Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House: Let's face it, Michael Sheen is the draw-card here. Peter Shaffer's play is full of words and wit, interspersed with snatches of music and spectacle, and it requires a triumphant actor to bring the bombast and pathos in equal measure. As he looks back on the rumours concerning his part in the untimely death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Rahel Romain), Salieri (Sheen) interprets events with a satirical detachment and studied indifference, barely concealing his passionate envy and desperate ambition. It is a masterly performance, and his voice and presence command our attention. This is important, because there a few occasions in the second act where the script becomes burdensome and the audience begins to realise that three hours is an awful long run time. Director Craig Ilott revels in the flamboyance and offers plenty of distraction. The costumes are sumptuous (Anna Cordingley and Romance Was Born) with the rich fabrics, sensational colours and flamboyant designs appearing particularly striking on the austere set (designed by Michael Scott-Mitchell). The black steps and folding doors hint at a keyboard, a ladder and an amphitheatre reflecting the action back to us as if we are witnessing our own foibles and Faustian pacts played out before us. Nick Schlieper's lighting design - heavy on the back-lit scenes - creates intriguing shapes, silhouettes and shadows, although some bits of staging can only be fully appreciated if seated in the middle seats as the sight lines from the sides would cut off a lot of the visuals. Besides the brilliant pairing of Romain and Sheen, other stand-out performances come from Toby Schmitz as an endearingly foppish Emperor Joseph II, Belinda Giblin and Josh Quong Tart as the frenetic Venticelli who buzz about the stage transporting news and gossip, and the musicians of the Metropolitan Orchestra who supply Mozart's sublime music which, despite Salieri's best (and indeed, worst) efforts, we all know and love.

- Grapes of Mirth - Contentious Character, Canberra: Merrick Watts hosted an afternoon of comedy at a winery: the more we drink; the funnier they get. The acts were Frankie McNair (who gets funnier at every performance - proving that comedy is hard work), Peter Helliar (telling comfortable and amusing stories like a favourite uncle), Nath Valvo (very energetic and forthright), Dilruk Jayasinha (probably the best of the line-up), and Geraldine Hickey who was not in a good mood and was clearly thrown by the drunken heckling. Although it was baking hot and there was insufficient shade, it was a good, fun day out; not side-splittingly funny, but with plenty of entertaining stories.

Friday, 19 May 2023

Friday Five: Spanning the year of theatre

Wednesday, 17 May 2023

Debunking the Myths: Inferior

Darwin in his The Descent of Man believed that women were

inferior because he couldn’t see any women doing the same intellectual things.

“The evidence appeared to be all around him. Leading writers, artists and

scientists were almost all men. He assumed that this inequality reflected a biological

fact.” In evolutionary terms, drawing assumptions about women’s abilities from

the way they happened to be treated by society at the moment is narrow-minded

and dangerous.

Those ‘Men are from Mars; Women from Venus’ type ‘theories’ remain

popular because anything that claims to explore sex differences is highly

sought-after by media outlets looking for clickbait articles. People who counter

that differences are not wholly due to genetics are often labelled sex

difference deniers, in a way that would never be introduced in debates about race

or colour; not since the 1950s, anyway. Sexual selection theories which were

proven to be incorrect and unscientific, however, are making a popular

comeback.

People are messy and come with preconceptions and prejudices. Saini

argues that it is impossible not to politicise scientific data and that neuroscience

has profound repercussions for how people see themselves. Humans are bound to

pick up attitudes and adopt behaviours based on societal expectations rather

than independent biological factors or sex chromosomes. We are also able to

change and adapt as recent research into neuroplasticity confirms that the

brain isn’t set in stone in childhood but is in fact mouldable throughout life.

Saini also debunks several myths, such as the one that women are better

at multi-tasking than men. The paper that was published on this subject,

actually never reported this claim, but the cultural and gender stereotypes

were stressed in the press release. A further belief is that in previous

cultures men went hunting while women gathered, making the males dominant.

Research by Bion Griffin and Agnes Estioko-Griffin into the Nanadukan Agta

refutes this assumption, suggesting that males did some tasks and females did

others. “By and large people did whatever they wanted to do. There was no

sphere of work that was exclusively male or female – except perhaps the killing

of other people. Women would stay back

when groups of men went out on raids of their enemies”.

Hunting was not the primary source of nutrition anyway, so the group

that hunted did not have the most crucial task. While studying the !Kung

hunter-gatherers in southern Africa in 1979, Richard Borshay Lee noted that women’s

gathering provided as much as two-thirds of food in the group’s diet, so gathering

was arguably a more important source of calories than hunting. It is also

likely that the first tools were digging sticks and containers for the food, which,

being made from wood, skin or fibre, would break down and disappear over time

leaving no record, unlike the hard-wearing

stone tools that archaeologists have assumed were used for hunting. “This is

one reason that women’s invention, and consequently women themselves, have been

neglected by evolutionary researchers.” Many of these myths began

because they fitted the dominant – male – narrative that positioned women as

inferior.

Humans are not automatically the same as other animals, and much of our

behaviour is more likely due to societal pressure than biological expression. Women

are not inferior, and the science that seeks to suggest this is the case is

inevitably flawed. It is time for this to be recognised and stopped. Sarah Hrdy

argues, “A feminist is just someone who advocates for equal opportunities for

both sexes. In other words, it’s being democratic. And we’re all feminists, or

you should be ashamed not to be.” This is the science we should all follow.