Never read about your heroes. Sir

Stanley Spencer may have been a brilliant and talented painter who created

works of magnificence, but it seems he was a very selfish and unpleasant

individual. His life, like his artwork, was unconventional and would have been

described at the time as Bohemian. At the time of the novel he is married to

Hilda (Carline) and they have two children, but he has an affair with a woman with whom

he thinks he shares a background, Patricia Preece. Patricia is in a relationship

with Dorothy Hepworth, which continues throughout her affair with Spencer. He divorces

Hilda and marries Patricia, who continues to live with Dorothy, and Stanley

returns to Hilda whom he cares for through cancer until her death. These are

facts and, therefore, not spoilers.

|

| Dorothy Hepworth, Patricia Preece, Stanley Spencer and Jas Wood at the wedding of Preece and Spencer (1937) |

The novel is narrated by Elsie,

who was the housekeeper and, at times, confidant to both Stanley and Hilda, and

she learns about and talks to the man in a manner that suggests her position is

obscure. She wonders how deeply to involve herself in the lives of these

people, about whom her parents have warned her, because artists are all a bit

odd. She claims to not want to cause difficulties, and yet she is keen to be a

part of the relationship. When Stanley paints her and calls the painting Country Girl, she is offended that he

sees her as a simple village girl, but he counters the painting is of “the girl

I’ve watched so closely, the girl whose neck I love, whose mouth, whose legs,

whose whole demeanour – not because I love them,

but because I love her. I called the

painting Country Girl because it

celebrates everything you and I have in common.” This is definitely not fact

but overt fiction. Supposedly the novel is more about Elsie than his wives,

Hilda and Patricia, but although Elsie narrates, we don’t learn much about her.

Maybe she just isn’t a very interesting character.

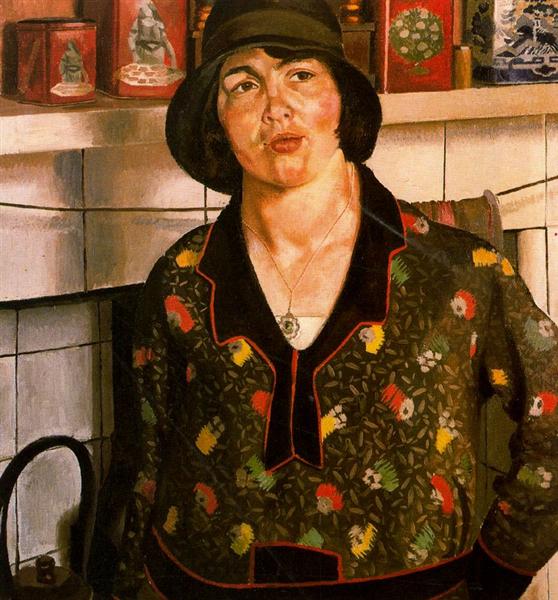

|

| Country Girl by Stanley Spencer (1929) |

Stanley makes all the women in

his life desperately unhappy, but Patricia seems to want him for his networks

and his introductions to galleries. She is very glamorous, but not as good a

painter as Dorothy, whose works she passes off as her own (with Dorothy’s

consent). After the breakdown of Stanley and Hilda’s marriage, Patricia wonders

whether to marry him or not, knowing she will be damned either way. “I’d rather

be a money-grabbing bitch than a penniless whore.” Dorothy warns her, “People

will take Stanley’s side. He has a talent for rousing sympathy, and the man is

never at fault when there’s a woman to blame.”

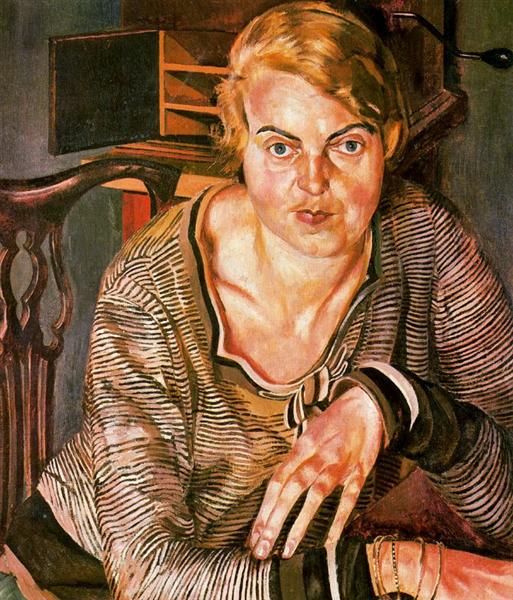

|

| Portrait of Patricia Preece (1933) by Stanley Spencer |

Hilda loves the garden and

growing things; it is holistic and she is skilled at it, although Spencer

dismisses it. On one occasion she brings in some snowdrops from the garden and

when Patricia visits with some exotic blooms she has bought, he dumps the

snowdrops out of the vase to replace them with the showy blooms, in an

obviously symbolic gesture. Metaphors are stretched a bit thin to cover Stanley’s

attitude to relationships and other people, as Hilda tells him, “Life’s one big

picture as far as you’re concerned. You put yourself at the centre of it and

paint the rest of us around you, hoping we’ll stay where you want us to. But

real people are different. Real people live and breathe and change, and not

only at the stroke of a brush.”

|

| Hilda with Bluebells (1955) by Stanley Spencer |

Spencer was skilled at organising multi-figure compositions such as in his large paintings for the Sandham Memorial Chapel, dedicated to the fallen of the First World War. He himself suffered from PTSD after the war, and tried to highlight and celebrate the mundanity of the army, including figures of men washing uniforms, cleaning tackle, studying maps, eating breakfast or making tea in his images. Spencer also has a complicated relationship with religion and, besides painting the artwork for the chapel, he paints Jesus into many of his pictures, often doing simple tasks as one of a group, not as the principle figure in the image, but as one of the crowd. He keeps a copy of St Augustine’s Confessions by his side while at work as inspiration. “There’s a passage about serving God through ordinary things. ‘Ever busy, yet ever at rest. Gathering yet never needing, bearing, filling, guarding, creating, nourishing, perfecting, seeking though thou hast no lack.’ As soon as I read that, I knew why I was there. It was all a service to God, even if I wasn’t fighting.”

|

| Paintings at Sandham Memorial Chapel |

Through his art, Spencer is intrinsically linked to Cookham, the village on the River Thames where he was born and spent many years of his life. He referred to Cookham as ‘a village in heaven’ and in his biblical scenes, fellow-villagers are shown as their Gospel counterparts, expressing both his unconventional faith and the compassion that he felt for his fellow residents. I know the area well, and I can picture the streets Nicola Upson writes about in the novel, and the train journey into London, which Elsie takes when visiting Patricia in the city.

|

| Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta: Dinner on the Hotel Lawn (1957) by Stanley Spencer |

No comments:

Post a Comment