Friday, 20 December 2024

Wednesday, 18 December 2024

My Newest Favourite Thing: The Percivals, Perc Tucker Regional Gallery

While we were in Townsville, I popped into the Perc Tucker Regional Gallery, mainly because it had air conditioning and was cool, but enjoyed the bonus of The Percivals exhibition.

Described as North Queensland's own biennial portrait exhibition, the competition, began in 2007, is open to all Australian artists to showcase their talents. There are prizes for paining and photographic portraits, and also one for animal portraits. How could I resist?

I have included the comments from the artists in quotes below each picture.

|

| Immigration - Annunciation 2023 by Nazila Janangir |

"The original inspiration for my work is a famous theme from Italian Renaissance paintings. The actual composition emerged from da Vinci's portrayal of the Annunciation. Revisiting the scenario, I tried to re-enact the event to tell the story of my immigration to Australia."Borrowing from the distant master, I depicted my subjects in an outdoor space, however, more contemporary, liberated, and alive. The double portrait of Gabriel and Mary also morphed into a double self-portrait; a metaphor for the announcement of the incarnation of a new persona.

"The depicted scene is one of the gardens at the University of Western Australia in which soaring pine trees embrace an elegant white elephant palm. This robust, fleshy palm with its ray-shaped leaves symbolises what the ancient rock has offered me since I reached Australia: an exotic life experience full of drama, passion and emotion saturated with huge everyday light.""My middle-aged husband, a loyal devoted family man and the sole income earner of a family of five, sat at our dining table, forlorn, weary from a three-month hunt for work, His sombre manner and downturned face contrasted sharply with the bright world outside. In that moment, he preferred the shadow of our family room to the promise of a bright day. This painting was designed to evidence his mood in colour and expression, to emphasise his age in form and posture, and to reveal his circumstances in choice of clothing and his placement within the domestic scene. I also wanted to contrast the interior gloom with a bright lit exterior (which he ignores), to signal how fully he is affected by the relentless burden of providing for our family, and how deeply he shoulders the heavy responsibility. He is pensive, weary in contemplation."

In-between Jobs 2024, by Karlalise Horstmans

Selves 2023 by Sarah Hickey "This portrait explores Gabriel Garcia Marquez's assertion that 'Human beings are not born once and for all on the day their mothers give birth to them, but life obliges them over and over again to give birth to themselves'."Inspired by Matryoshka dolls, the image represents the concept of duality: a higher self and inner critic, a mother self and a child-like persona, the internal vs the external. I wanted these personas to coexist, interconnect and harmonise with one another."In this piece a larger self protectively cradles a smaller version. Two avian guardians sit on my shoulders - a connect to spirit - while we both hold a sword-like paintbrush. Granny squared blankets and Suzani motifs symbolise life's cyclic nature, the knitting of time, and the enduring importance of change and growth."

Reverie 2024 by Marco Pennacchia

"In my painting Reverie, I aim to capture the profound emotional depth hidden within my inner self, serving as a manifesto for personal freedom often suppressed in today's society. Emerging from a culturally restrictive background, I grapple with expressing my inner femininity, a predominant theme in this oil artwork. Delicately veiled by linen fabric, the subject's forms and facial expressions subtly emerge, symbolising the complex emotions concealed within."Reverie portrays my vulnerability confronting fears and insecurities while revealing my true self to the world. It explores the dichotomy between external appearance as a visual facade and the intrinsic essence that defines our humanity. Through this introspective piece, I challenge viewers to contemplate the depths of their own inner selves and the courage required to embrace authenticity in a society that often demands conformity."

How the Light Gets In 2023 by Seabastion Toast

"Over two decades ago, Karlee Rawkins and I embarked on our undergraduate life together. While life led us down different roads, fate has brought us back to the same community once more.

"In creating this portrait, I sought to capture the essence of Karlee's world - a world illuminated by the winter light streaming through the windows of her home. This play of light and nature serves as a symbolic representation of her work, which delves into the profound connections between wildlife, nature, and the human psyche.

"Amid the chaos of family life, she radiates a meditative serenity, an unwavering devotion to her craft always at the forefront of her mind. Her life and art are inseparable, a testament to her enduring commitment.

"In the distant doorway, you'll find her son's silhouette, a powerful symbol of her transformation from a solitary studio artist to a loving mother, disability-rights advocate and artist."

|

| The Man Under the Hat 2024 by Barbara Cheshire |

"Prior to interviewing Bob Katter, the only knowledge I had of this man was the negative comments the media printed and that perhaps he was a man of the land. However, talking to the folk from Northern and Western Queensland and with the man himself for a considerable time, a different and intriguing picture emerged. This active hands-on helper who looks out for Queensland has a wicked sense of humour and is smart as whip. You only need to flip through the book he has written to appreciate his knowledge. Although Bob tells it like it is despite the possible backlash, he is the longest-serving member of Parliament and an interesting subject to paint."

Self Portrait with Purple Gove 2023 by Christine Wrest-Smith

"This painting reflects the level of concentration I adopt when painting a self-portrait, requiring the scrutiny and objectivity needed to study one's image."I was drawn to the idea and risk of wearing a white shirt while working - the medium and process of oil paint being the natural enemy of the clean and crisp shirt."Many artists wear gloves when painting for health reasons; the skin is porous and some pigments need to be used with care. But the wearing of gloves has potential narratives on offer."As I initially considered the inclusion and colour of my gloves for this work, a meaning and purpose sprang to mind."The colour purple symbolised the Suffragettes women's movement at the beginning of the 20th century, so for me, the very appropriate context for my purple gloves is to represent the strength of women in every aspect."

Bereavement (Dad's death mask on his death bed) 2023 by Lisa Ashcroft

"My father died last year. I arrived just an hour after his passing due to a flight delay."As I stood by his bedside, his body still retained warmth, but his once gentle and serene face was now contorted and twisted, his body bent and buckled by the ravages of dementia. He was no longer the man I knew, stripped of his geniality and senses."In that surreal moment, time seemed to slow down, enveloping us in a scene reminiscent of a Caravaggio painting. The room closed in around us, every detail magnified."The pattern on the bedspread resembled a tide of crucifixes, reminding me of his upbringing in a Catholic orphanage. memories of his life achievements and accolades flooded my mind, mingling with the raw onset of grief."My father, Philip Ashcroft, was immortalised in my mind's eye as I witnessed his final moments. This painting captures the essence of his passing - a raw, honest portrayal that was emotionally wrenching to create.

|

| Rise 2003 by Christine Baker |

"The work is about playing it safe and keeping a regular job. The raincoat symbolises protection from the weather but also protection from taking a step into the unknown. The older figure at the top always wanted to be an artist but worked a regular job for security. the young adventurous soul always remained within and finally the older soul took the step to become an artist."

"I have been experimenting with using various liquids as a means of creating spontaneous gestures within my work. This purposeful, distorted self-portrait is a challenge to myself on what a photograph can be. The refracted and reflected light playing off the peaks and troughs of the water project a familiar image of reflection. Yet, during this suspension of movement, the water reveals a distorted and often grotesque image of self. The way in which the image appears is also reminiscent of agitating a developer tray and revealing a black-and-white darkroom print."

|

| A Portrait Within Art 2023 by Christine Hall |

"I selected Pam Walpole, a highly regarded contemporary landscape artist, to be part of my book titled 'Artists in Studios'. She has won many awards, more recently the Pamela Whitlock Prize. I am endeavouring to portray Pam as part of the work - leaving a fraction of herself immersed in the art. Capturing an inner portrait of Pam with her expressive brushstrokes - her face mesmerised and hands give an insight into the passionate depths the artist can transport us to."The process of an artist remains unique and individual. the symbiotic relationship between the art of photography and the artists' work complement each other."

"The sharp lines of his black suit speak of professionalism, yet their sombre hue betrays a deeper truth. The weight of expectation, the pressure to provide, and the expectation to succeed plague his mind. This is a portrait not just of an individual but of a system that demands conformity, leaving countless others navigating its labyrinthine paths in search of a place to belong."

"The Rocketgirl's journey started as a stress response to the pandemic restrictions, but lasted way beyond that, as the little astronaut kept exploring her surroundings, feeding the child's curiosity, learning about the universe and looking for her place in it."This image is one of the memories from small but magical worlds discovered in our backyard at the strangest of times. Looking at the world through the eyes of a child reminds us of one special power we all have but often forget after becoming grown-ups: the power to imagine."

These two ceramic works were part of a different exhibition entirely, but I really like their colour, boldness and sense of fun.

|

| Ceramic Head II (Cat Lady) 1990 by Robert Burton |

|

Gaia 2015 by Nadja Burke |

Friday, 13 December 2024

Friday Five: Festive Flamingos

Are flamingos festive? Who knows. I do know however, that the group name for flamingos is a flamboyance, and that sounds wonderful to me. And because I know there are only four cross-stitch designs and I'd hate for you to feel shortchanged on your Friday Five, here are a couple of bonus facts.

- There are six species of flamingo, four of which are found in the Americas, and two of which are native to Afro-Eurasia.

- The flamingo is the national bird of the Bahamas.

- The word flamingo is thought to derive from the Portuguese or Spanish flamengo, meaning flame-coloured.

- Flamingos are not born pink (hatchlings are a cute fluffy grey), but they obtain their hue through their diet of aqueous bacteria and beta-carotene. A well-fed, healthy flamingo is more brightly coloured (and, therefore a more desirable mate), whereas a pale flamingo is usually unhealthy or undernourished.

- The middle joint of a flamingo's leg is the ankle, not the knee, which can give the impression of their legs bending backwards while walking.

Friday, 6 December 2024

Friday Five: Books Read in November (Yes, it's actually just four)

- The Scent Keeper by Erica Bauermeister (St Martin's Griffin) - This novel blends whimsy, magic realism, coming-of-age self-discovery, fairy tale archetypes and young adult fiction. Emmeline is raised by her father, alone on an island which can only be reached once a month when the tide is right. He has a machine, which can capture scents and print them onto slips of paper, like a Polaroid camera for images. He puts these scent papers into small glass bottles, stoppered with different-coloured wax. The scents do not last forever, and he begins to burn them individually to release memories, until a tragic accident forces Emmeline to leave the island and return to the mainland. Emmeline’s father has educated her through stories, foraging and fishing, sitting her down for a lesson every morning. There is an element of Miranda and Prospero, and her awakening to the brave new world enables the author to indulge in the trope of an ‘alien identity’ discovering and describing technology. She learns to read people through their scent, like a dog does. When rescued and taken to school, Emmeline is bullied for being different and for her intense sense of smell and her natural style – she doesn’t understand falsity and masking. Later, her mother, Victoria takes her to a make-up counter and buys all the products after the ‘transformation’. Emmeline goes to work for her mother creating scents to make people spend money. Often she omits a significant element, to force the body to fill that absence. "And what if that missing thing could make a person need to buy the things around them?” Of course, the skill is used for capitalist gain, but the sentiment is true for art – visual, performance and written – the best leaves something for the audience to do; to provoke a response rather than telling them exactly how they should think and feel. Many aspects of the novel are unconvincing, and it is not enough to pass this off as magical realism when they relate to plot points. Neither is it satisfactory to suggest they don't matter as this is a coming-of-age young adult fairytale, with Emmeline learning to 'be her own person'. Who else would she be?

- In Memoiram by Alice Winn (Viking) - In Memoriam is reminiscent of Atonement and Testament of Youth as it covers the doomed generation of young men who went to war and never returned, either because they were killed or changed irrevocably. Also discernible are elements of Pat Barker’s Ghost Road novel, wherein, like the WWI poetry we all studied in school with the benefit of hindsight and distance, we can plot the way innocence, ideology and excitement turned to disgust, betrayal, anger and frustration. Our characters transform from schoolboys worried about their families and duty to wounded and embittered cynics whose promise was destroyed by a class system into which they had no input. And at its heart it is a love story between Gaunt and Ellwood, two young men coming of age in a time when homosexuality was still illegal. Winn writes in linear style, with sharp, clear sentences, avoiding excessive adjectives, but with a profoundly moving poetry. There are echoes of Blackadder Goes Forth in the trench talk, where there is resentment of the upper class automatically being made officers and promoted to captains, having authority over men much older and more experienced than them. Meanwhile the men are falling without class distinction in a horrifically mundane manner. “At nine, they went over the top. West’s head was shot off before they had gone two feet. Elwood paused to look at his brains. Pritchard had always said he didn’t have any, but there they were, grey and throbbing and clotted with blood.” The section set in a prisoner of war camp is almost a comic diversion. “It’s astonishing how well an English boarding school prepares one for prison.” All the prisoners are bored, chatty and trying to escape, while the guards are generally good-natured and long-suffering. In Memoriam is Alice Winn’s debut novel. It may not be an original topic, but it is excellently written. She writes captivatingly about things of which she can have no first-hand experience: life in the trenches, male sex, and English public schools with a ring of authenticity. I look forward to her next offering.

- Dancing Cockatoos and the Dead Man Test by Marlene Zuk (W.W. Norton & Company) - Subtitled, How Behaviour Evolves and Why It Matters, this book answers that question immediately. “If we assume that intelligence is predetermined, we are less likely to think interventions, say in the form of social programs to improve learning in children, will be effective. On the other hand, if we assume everything can be altered by our actions, we may blame the victim, as is sometimes seen in the suggestion that those with cancer or other serious diseases could have avoided their plight by diet or exercise, or that people can just think their way out of depression.” The nature/ nurture question is repeatedly addressed as a 'zombie idea' - one that keeps springing back to life no matter how many times it has been disproved. Most recently (in 2017) a New York Times article titled ‘The Unexamined Brutality of the Male Libido’ argued that we are simply stuck with brutish men who can't or won't examine their destructive sexuality because it's just basic male behaviour. The book also questions the theory of exceptionalism, which puts humans above other species and supposes that other species are intelligent or sophisticated the more they are like us. “It doesn’t make sense to simply pick on an animal, no matter how beloved, and try to rank it according to a scale that only works in a single dimension or on humancentric traits… In other words, dogs are good at things that make sense for dogs to be good at.” The idea of lizard brain is popular because it allows us to classify less-desirable behaviours and dismiss instincts as a holdover from the past. It is simple to understand, doesn't require complicated scientific explanations, and is completely untrue. What is true is that environment and genes interact to produce behaviour; as illustrated in a fairly devastating section on animals kept in captivity, or in the chapter on gender. This book is full of explanations, stories and science, and it is fascinating reading.

- Orphia and Eurydicius by Elsie John (Harper Collins) - In this adaptation of the Greek myth, the sex of Orpheus and Eurydice are switched, but it also concerns the story of a true love of equals without society's gender-ascribed roles. Orphia learns fighting from her brother (Apollo) and poetry from the muses; her poems make flowers bloom and waters move. As Calliope, the muse with responsibility for epic poetry, instructs, "No riches on earth compare to the arts. Tell me - what is it to feel, to express, to take delight, to see oneself reflected, to experience the stories of others?" Many of the stories Orphia learns are different from the male-centric myths that have been handed down: Hera, Medea, Atalanta and others all have greater agency. The gods use mortals as playthings and their assistance - like the advice of the Oracle - is to be treated with caution. Orphia plays games with Eurydicius and they converse as equals, as she notes, "He was gentle, and sweet; thoughtful and quietly kind. They were not the qualities that men prized, but I thought they were among the greatest qualities a man could have." When Eurydicius dies, Orphia uses her poetry as a challenge and a weapon in her desire to return to him, and when she goes to the Underworld she refuses to go gentle into that good night. "I will speak the two of us into legend, if I have to draw each letter from my own marrow. I will become poetry as I die." This is a beautiful retelling of a classic myth incorportaing poetry, creativity, unconventional love, and the courage of women who refuse to be silenced.

Friday, 29 November 2024

Friday Five: Bits of Theatre Reviews

- Away - Canberra Repertory Society, Theatre 3: This is considered an Australian classic, and it is treated as such, with weighty moments and dragging pauses. It tells the story of three internally conflicted families holidaying on the coast for Christmas, 1968 and, according to Wikipedia, is one of the most widely produced Australian plays of all time, being on the school curriculum in many states. It incorporates several moments of Shakespeare which don't so much subtley enhance the story but profoundly crash into it to try and suggest merit. This production doesn't hang well together, with some self-indulgent drama school moments (the storm at the end of the first act is enacted by cast practicing physical theatre in the way that non-theatre people is typical am-dram), but the sound (Neville Pye) and lighting (Nathan Sciberras) are excellent with a multitude of notes, techniques and colour to enhance the production. A variety of acting styles speak of a lack of cohesion - Callum Doherty excudes a flamboyant melodrama as Tom, a teenager with leukemia trying to experience all he can while he is well enough, while Andrea Close as Coral portrays the ups and downs of someone medictating through grief with great sincerity. The stage is not used to its full extent and scene changes are uneven - some of the cast remain in character to perform them; others don't. The play-within-a-play is appropriately intimate, and the half-painted scene for the 'beach' in the second act is evocative, although some of the kodak screen images are poorly projected and detract from the overall ambience. A stronger vision from director Lainie Hart communicated more clearly to all cast and crew might have helped this play find an even keel.

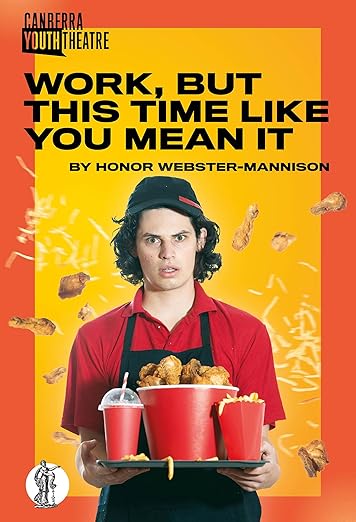

- Work But This Time Like You Mean It - Canberra Youth Theatre, Courtyard Theatre: A play about young people's first experiences in the workplace explores subjects such as trying to survive and have a good time on a minimum wage, dealing with demanding customers and irritating colleagues, and the realisation that this might be all there is for the endlessly foreseeable future. Written by Honor Webster-Mannison, the script won the 2022 Emerging Playwright Commission, and this production is really not as bleak as that might sound. Working in a fast food outlet (no names but it is red and yellow and the actors dress in chicken suits at one point), the characters are simply called after their positions, such as Shift Manager, Drive, Deep Fryer, Kiosk, etc. and perform repetive gestures, throwing and catching balls in synchronised movements. The young actors are mainly self-satisfied and have little rapport with their fellow cast members, with the possible exception of Kathleen Dunkerley as Register 1 (good range of pace and emotion) and Sterling Notley as Food Prep (measured and generous performance providing a foil to other actors). The set (Kathleen Kershaw) is the highlight of the piece, marking the transition between childhood (a soft play centre) and the slippery slope of post adolescence with a bright and obvious visual metaphor of a ballpit. Multiple overlapping voices, recorded speech, video games projections and dance breaks all add to the anarchic feeling, as directed by Luke Rogers, but each one of these elements could have been explored more thoroughly, instead of too many ideas appearing under-realised. The play has interesting moments and deliberately descends into chaos, but the unstructured disorder soon becomes tedious and looses the audience engagement.

- Play Me Something - Green Oak Theatre, Belconnen Community Centre: Four short plays with no apparent direction (although Shaylie Gillies is credited) or cohesion. INT.THEATRE by Amelia Chittick is a play about actors preparing to do a play, while Sir Harry vs, The University by Bart Meehan is a well-written comedy about a disgraced actor who applies for a job at a university only to sue for discrimination when they don't get the role. I was surprised to see that Blame by Shaylie Gillies is about the effect on the community of the Aberfan disaster, until I was told that the event featured heavily in the TV hit show, The Crown, which would explain why people in Australia suddenly know about it. The last play on the bill is The Bridge, also by Bart Meehan, which deals with family loss, grief, difficult relationships and distorted memories. Due to the changing sets required, these were necessarily perfunctory, although the use of sheets in Blame is interesting, and the Greek chorus effect adds a much-needed diversion. I also admire the decision not to make the cast attempt Welsh accents. Actors performing in different pieces are at best competent and have clear favourites, interpreting these and mumbling inaudibly through others. For example Chazelle Cromhot plays Professor Turner with solid gestures in Sir Harry, obviously relishing the role, while leaving unnecessary pauses and being almost completely uncommitted to the role of Daughter in The Bridge. While I applaud the motivation to bring short plays to the stage in search of a wider audience, the performance feels under-rehearsed and could be considered a drama exercise, but not a finished product. The poster is a highlight.

- The Inheritance Pts 1 & 2 - Everyman Theatre, ACT Hub: Seen over two nights (or for a solid six hours on a day with a matinee), this is a massive work of friendship and death, intended to be a re-imagining of E. M. Forster's Howard's End. It deals with homosexuality in the 1980s, so of course the promising young men are struck down by AIDS, in that decade's anthem for doomed youth. This is an intergenerational piece as the contemporary couple, Eric Glass (James McMahon) and Toby Darling (Joel Horwood) deal with the inherited trauma of that era through their privileged existence in Eric's family-owned apartment in New York. They are surrounded and embraced by a coterie of quasi-intellectuals, who shuffle bare foot across the boards, offering metaphorical foils if not rapier-like wit, and draping over each other to produce carefully posed tableaux. Self-referentially enough, Toby's semi-autobiographical novel is due to be adapted for Broadway, and he involves himself in the writing and the auditioning of himself through the character of Adam McDowell (Andrew Macmillan). It's full of in-jokes and meta-theatrical references, and it's actually quite hard to like these characters as they lounge about the stage reading and pontificating as though their every utterance holds weight. It doesn't. It's didactic and preachy and finishes with a monologue from Margaret (Karen Vickery), the only woman of the thumpingly male show, who loves all the rogues and scamps. And yet. Director, Jarrad West has done wonders with the material, not least in finding twelve men of solid acting ability. Joel Horwood's petulance is compelling, James McMahon's brooding presence is powerful, and Duncan Driver delivers an excellent commentary as the unfairly criticised E.M. Forster (why didn't he make his sexuality public?). There are simulations of sex and abuse, but the moment where an actor leapt into the arms of his acolytes who failed to catch him, leaving him crashing into the stage, was the one that really brought tears to my eyes.

- Bloody Murder - Canberra Repertory Society, Theatre 3: Canberra Repertory traditionally stages their final production of the year as a fun night out in which audience and actors main purpose is to have fun. This is achieved in Bloody Murder, written by Ed Sala and directed by Josh Wiseman. The premise is that the characters in a quintissential country house murder mystery get fed up with playing the same old roles and turn upon the author (and the audience) to forge new ground and subvert their sterotypes. Antonia Kitzel is the matriarch of the house, Lady Somerset; Glenn Brighenti is her nephew, Charles, waiting in the wings to inherit her fortune, Steph Roberts is the maid in the ridiculous sexy French maid outfit favoured of male directors while delivering a Sybil Fawlty-esque performance, Arran McKenna is the war bore, an uptight mayor from India via central casting, Stuart Roberts is Devon Tremaine, the alcoholic has-been actor, and Holly Ross is Emma and the Countess, with a variety of accents with which she has a lot of fun, although I would caution that self-satisfaction on stage doesn't always equate to enjoyment from the audience. This is an ensemble piece so there are not meant to be stand-outs, but Aaron McKenna and Stuart Roberts both excel in their commitment to harmonious performances, never pulling focus, remaining pitch perfect in vocal and physical delivery, and offering supportive presence demonstrating superior textual understanding. The technical details all serve the play well, particularly the sound where Neville Pye is in his element, heightening atmosphere in an ironic manner from creaking floors to sensuous foreboding mood music. When it remembers not to take itself too seriously, this play is a lot of fun.

Wednesday, 20 November 2024

Townsville’s Palmetum

When we learned a good friend had died, we had been expecting it, but were still devastated. We were in Townsville at the time and we went to the Palmetum to reflect. It's a botanic garden displaying one the largest and most diverse public collections of plams in the world. Botanic gardens make me feel calm - there is a reassuring sense of life, growth and continuity. It was what I needed to find peace.

I haven't really got words, so I will just share images.

|

| In the avenue of Bismarkia nobilis |

I find spirals and circles comforting as they return to their beginnings and intimate infinity.

Some of them remind me of corals and marine plants and animals - I suppose nature uses similar formations throughout all environments.

Labels:

avenue,

bantanic gardens,

cactus,

circles,

continuity,

death,

flowers,

gin,

green ants,

Him Outdoors,

insects,

life,

nature,

palm trees,

Palmetum,

peace,

spirals,

Townsville,

water,

Xerophytes

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg?format=2500w)