Normally, this post would cover my five favourite films of the year. But, as I think we can all agree, there is no such thing as 'normal' in 2021, so I'm having ten, even though it's a Friday Five. The films just have to have been released this year in Australia (where I live). So here they are, in alphabetical order:

- De Gaulle: Has a strong vibe of Darkest Hour for French people, and Tim Hudson plays a wonderful Winston Churchill.

- The Deep House: A couple exploring a haunted house with dark secrets is a familiar genre. He is controlling to the point of exploiting her fear and vulnerability for his own amusement. She craves his affection; he craves ‘likes’ on his social media pages (and we know that controversy generates more attention). Putting this claustrophobic setting and relationship underwater is inspired. The house is at the bottom of a lake and the couple dive deep into all sorts of metaphors and horror tropes as they run out of air, escape routes and plot credibility. The narrative holes and limited acting ability are mitigated by the underwater photography and the perspective-shifting concept. If you like budget horror that explores psychoses, then this is disturbingly good.

- Don’t Look Up: It's an American satire: neither of those things are noted for their subtlety, indeed exaggeration is one of the defining features of the genre - 'satire: artistic form, chiefly literary and dramatic, in which human or individual vices, follies, abuses, or shortcomings are held up to censure by means of ridicule, derision, burlesque, irony, parody, caricature, or other methods, sometimes with an intent to inspire social reform' - so I’m not sure why people are criticising it for that reason. In this story, a comet is hurtling towards earth and will wipe us out, but the conspiracy theorists think, 'That's what they want you to believe, sheeple'. Of course it's obvious, but like the man says, it's based on truly possible events. Oh, and it's got a star-studded cast playing up stereotypes to the max.

- Lapsis: Director, writer and editor, Noah Hutton, gives us an epic work about the exploitation of gig-economy workers and the evils of capitalism through a low-budget but high-concept sci-fi action thriller. Perhaps if we joined together and helped one another rather than constantly competing for individual success, we would all gain, rather than just the big bosses profiting from our labour. Oh, wait, that's socialism - it will never catch on; at least not in America.

- News of the World: Travelling the country and reading snippets from the newspapers to illiterate communities sounds like my ideal job. The ever-reliable Tom Hanks is the ideal person to do it. Oh, and he also takes it upon himself to return an 'abducted' child (Helena Zengel) to her aunt and uncle on the other side of Texas. Paul Greengrass directs a solid Western which is almost a love letter to the genre, with all the usual tropes viewed from a different angle. The contemporary politics are a touch too obvious as there is a lot of colonial guilt for which to atone, but it's a generally uplifting film which attempts to sow some seeds of hope for the future.

- Nobody: Incredibly violent and full of stylised toxic masculinity, but Bob Odenkirk is an extremely likable actor and his character is kind to a kitten in the first scene, so I've given him (and consequently the film) an extra star.

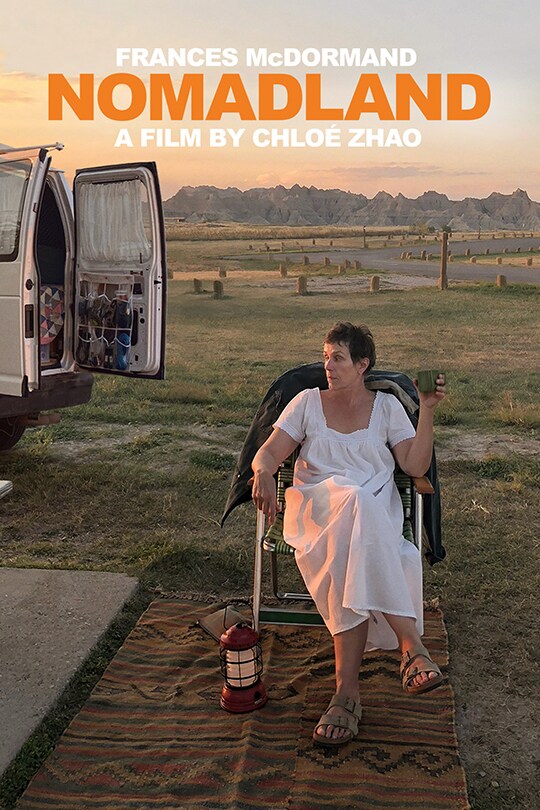

- Nomadland: Frances McDormand plays Fern, a woman who is 'not homeless but houseless' as she travels the United States looking for work as if in a modern version of The Grapes of Wrath. She is seen cleaning toilets in truck stops, boxing up goods in the soulless Amazon warehouse, or sorting beets in Hardy-esque scenes, but there are also wide sweeping vistas of the incredible scenery of this beautiful country. There is only a finite space for self-made millionaires, capitalist growth and rampant individualism - the rest of us have to share the planet, and the conversations held at a closed dinosaur park are laden with metaphor.

- The Power of the Dog: Excellent slow-burner with intense and toxic relationships against a stunning backdrop of Central Otago (standing in for Montana). Jane Campion knows how to bring out subtle nuances, which don’t stand out like dog’s balls, but reward the audience’s attention. It would be nice if women were given a little more agency (because Kisten Dunst deserves an equally dynamic role as Benedict Cumberbatch, Kodi Smit-McPhee and Jesse Plemons) but then I guess at least that’s probably true to life.

- Promising Young Woman: Carey Mulligan is amazing and the treatment of this horrendous material is well-handled by director, Emerald Fennell. At times it has a graphic novel/ raunchy thriller vibe, because, like, how else are you going to get the entitled would-be rapist frat-boys to watch it, right? These are the boys that whine, ‘Why do you have to ruin everything?’ when a woman dares to stop their 'fun' with an accusation of abuse. Yes, we’re f*#^ing angry!

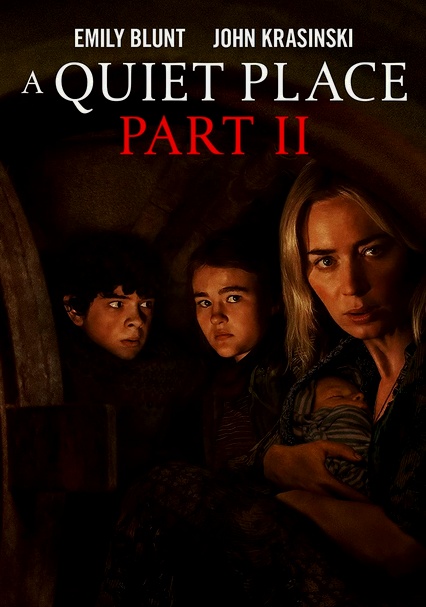

- A Quiet Place Part II: In which the younger generation step up, Cillian Murphy learns some essential sign language, and the sound editing deserves all the awards.