A Room Made of Leaves by Kate Grenville

Text Publishing

Pp. 319

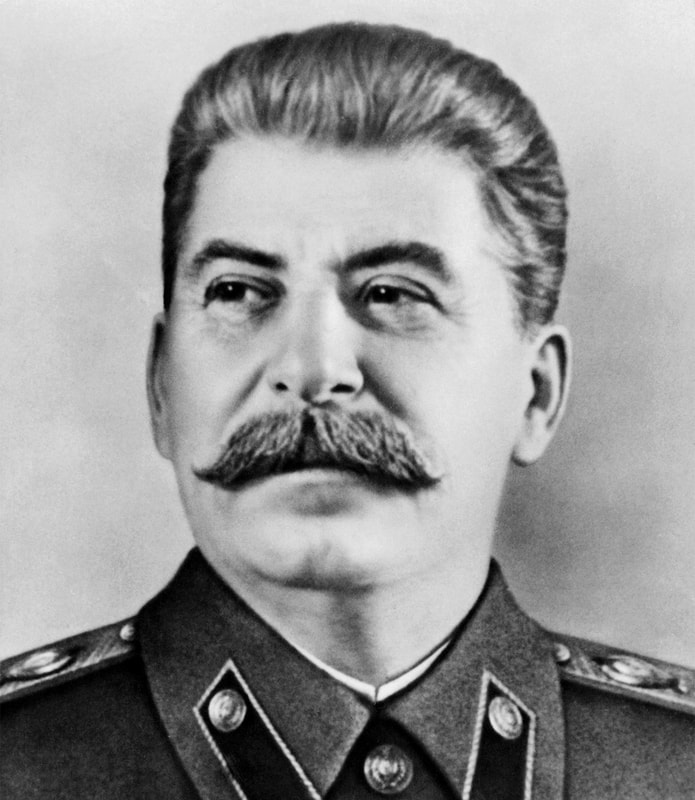

Supposedly this novel is a memoir by Elizabeth Macarthur, “wife of the

notorious John Macarthur, wool baron in the earliest days of Sydney”. It is

not, and we know it is not through a variety of fictional and literary devices,

not least of which is the opening admonishment to “do not believe too quickly”.

Kate Grenville has examined papers and letters written by Elizabeth Macarthur,

and she tries to suggest what may be hidden between the lines as she reflects

upon her sentence construction, and she peppers the memoir with speculation and

modern sensibilities in relation to her feelings about ‘the natives’ and gender

roles. Seen in this light it is a playful exercise in historical

representation.

There are echoes of Eleanor Dark’s Timeless Land trilogy, as the new

arrivals to Sydney Cove and Parramatta interact with the locals. Politics and

personalities are surmised in short sketches, such as the temperament of

Governor Arthur Phillip, and the conflict of struggling to acquire rights to

land, of which no one had rightful ownership, is a central theme in the novel.

The premise is that it is Elizabeth who knew about breeding

sheep, from her past life being raised on a sheep farm, and that she hid her

skills behind her husband’s bombast. It is Elizabeth who is at the centre of images

of wool and breeding combined with metaphors of tupping rams and protection of

lambs, rather than John Macarthur. Macarthur himself is portrayed less than

favourably, as “rash, impulsive, changeable, self-deceiving, cold, unreachable,

self-regarding.” His character, however, is also assessed with a modern medical

understanding of mental health. “My husband was someone whose judgement was

dangerously unbalanced. There was a wound so deep in his sense of himself that

all his cleverness, all his understanding of human nature, could be swept aside

in some blind butting frenzy of lunatic compulsion.”

|

| Australian $2 note featuring John Macarthur and a merino sheep (designed 1965) |

This contemporary approach is echoed in the

understanding of gender roles. Elizabeth reflects on the sexual experience with

a modern cognisance of rape within marriage. She succumbed to him back in a

hedge in Devon early in their courtship when she was flattered by his

attentions and interested in what she viewed as an agricultural procedure. The experience

left her pregnant and, with no rich protector, marriage was the best option she

could hope for. Later, when she sees the treatment of female convicts, she

feels compassion. “Mr Macarthur maintained that every one of these women was a

harlot who deserved nothing better, but I did not believe him. By now I had

learned enough about the narrowness of a woman’s choices to guess that they

were not all harlots, only less lucky than I had been.”

Her morals are compromised when she has a liberating

sexual affair with William Dawes, the colony’s surveyor, astronomer and

mapmaker. This is entirely supposition on Greenville’s part and, although it serves

the narrative, one wonders what Macarthur’s descendants make of this fictional

fabrication. Dawes instructs Elizabeth in scientific adventure while conducting

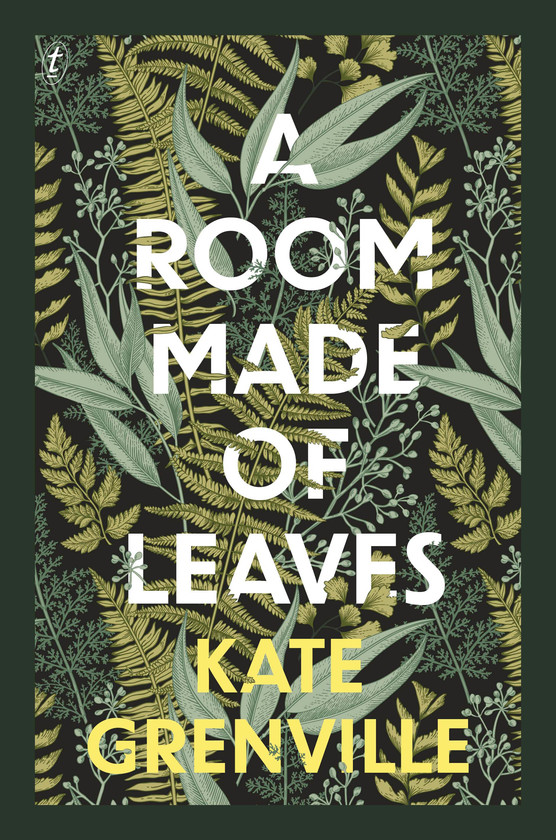

an erotic entanglement in a secret bower; the ‘room of the leaves’ of the title

and the exquisitely designed cover. The parlours and salons of this world are

stifling, while the outside world is wild and permissive, which is made

abundantly clear. Elizabeth abandons herself to pleasure with another man, and

also with herself, exclaiming, “How much better to have your own true self for

company than to be lost in the solitude of an unhappy marriage.”

In the midst of the affair, she considers her

connection to the particular part of the land on which she has experienced

happiness, even though she knows it is ephemeral. The tone is one of the

current reflection of reconciliation and understanding of the indigenous

ownership of land, which does not seem to be recorded at the time. She knows

that she is on Burramattagal land, and, although she takes it from them and

farms it for profit, she condemns others who do the same: “Every settler with a

deed in his pocket felt entitled to chase away the tribes from the land that he

thought now belonged to him by virtue of that piece of paper.” She considers

the fact that they “obstinately remained” with something reflective of settlers’

guilt.

The intricate weaving of the woodland copse is

reflected in the capricious construction of the narrative, as Grenville teases

out fancy from the few facts available. Elizabeth writes of her letters home, “I

composed a glorious romance about all this for my mother. I would not lie, not

outright. I set myself a more interesting path: to make sure that my lies occupied

the same space as the truth. I am reading over the copy now, decades later,

with admiration for my young self.” She twists apparently finding fun in this

obfuscation, as a demonstration of her wit and intellect, just as Grenville

does in her own interpretation.

She

addresses us directly as Elizabeth, warning us not to put too much faith in the

written word. “And, if I may tease you, my unknown reader, let me remind you

that you have only my word for any of this.” This is a novel rich in

imagination and confident in structure, which plays with the reader in a way

one may find charming or sly, or possibly both.

|

| Portrait of Elizabeth Macarthur by an unknown artist |