- Quichotte by Salman Rushdie - Shortlisted for the 2019, Quichotte, is a breathtakingly sophisticated novel of postmodern genius, featuring a picaresque style and a desperately ordinary protagonist. Sam DuChamp is an Indian-born writer living in America, who has written a number of unsuccessful spy thrillers. Hoping to write a book "radically unlike any other he had ever attempted", he creates the character of Ismail Smile, a travelling pharmaceutical salesman. Having worked for unscrupulous companies and suffered a stroke in old age, Smile begins obsessively watching reality television and becomes infatuated with 'celebrity' and former Bollywood star, Salma R. Despite having never met her, Smile sends her love letters under the pen name of Quichotte and begins a quest for her across America with his imaginary son, Sancho. It is a spectacular piece of literary satire, which confounds simple synopses, as it is impossible to separate what is 'real' and what is not. That is clearly no accident in this post-truth society in which we find ourselves.

- The Opal Desert by Di Morrisey - Di Morrissey sets place extremely well. In her dozens of novels, the scenery and landscape are immediate and infinitely better drawn than her characters or plotlines. The Opal Desert is, unsurprisingly, set in Lightning Ridge, Broken Hill, Opal Lake, and White Cliffs, where most people are exceptionally friendly and we learn about the precious stones and the community who mine them. The three women around whom Morrissey tells her tale, Kerrie, Shirley and Anna, are all fairly predictable stereotypes who overcome their personal obstacles in life-affirming ways, which may not be realistic, but are heart-warming. Many people head to the opal fields for a change of pace, which is admirable. One character states, “We all need time out, as they say, on occasion. But that’s all it should be, a space between decisions. It becomes very easy to drift. You see it happen out here and before you know it, you’ve lost a great chunk of your productive life.” This begs the question, why must you be productive; what is the definition of produce – is it capitalist growth, and is that why Indigenous culture is ignored because it doesn’t visibly contribute to the GDP? What is wrong with “drifting”? Perhaps it has to do with the nature of Morrissey’s storytelling, in which all is tied up neatly at the end. It seems easy to get to be a curator, train for world athletic events or have an exhibition of paintings. Other character’s mysterious circumstances are cleared up in a page or two and everyone gets closure. This makes the people instantly forgettable (so much for recording their stories) but the landscape lingers in the mind.

- Bewilderment by Richard Powers - Shortlisted for the 2021 Booker Prize, Bewilderment is a deeply moving and powerful novel, set in the near future. It concerns the degradation of the planet in tandem with a father's love for his neuro-divergent son. In an interview for the Booker Prize, Powers said, "It is, in part, a novel about the anxiety of family life on a damaged planet, and for that, I'm indebted to writers as varied as Margaret Atwood, Barbara Kingsolver, Evan Dara, Don Delillo, and Lauren Groff." It is a rich novel full of connections as, grieving for the loss of the wife and mother, the two embark on a camping trip in the wilderness to heal through nature. When they return to the 'real' world of work and school - competition, conformity and bullying - they are introduced to AI technology which can help connect to memories of others and suggest life in parallel universes. Some reviewers have considered it didactic and claustrophobic. Perhaps this is intentional as, if we continue to ignore the environmental portents, are we endangering our own species as the world closes in on us?

- Shit, Actually by Lindy West - Lindy West is a New York Times opinion writer and best-selling author who used to be the in-house movie critic for Seattle’s alternative newsweekly The Stranger – with a genuine adoration for nostalgic trash. In this humorous feminist revisionism re-evaluation of cult and classic films (re-watched during lock-down), she ranks all films against The Fugitive, which she thinks is the perfect film – Love Actually is the worst (why don’t any of the women actually talk?). Featuring rants, all-capital letters and italics, slang, swearing, and erratic punctuation, it reads like a teenager’s texts, complete with hashtags and initialisms such as YOLO and BTW. Other than Love Actually and Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (called Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone here), all the films are American blockbusters. As West writes, “I’m sorry but if there’s a British guy in a suit who talks in the first five minutes of your movie, he’s the villain! If it’s Tom Wilkinson, you’re fucked.”

- Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus - I have read this for not one but two book clubs, for which it is the perfect fare. Although a brilliant chemist, Elizabeth Zott is not taken seriously because she is a woman in the 1950s and, “When it came to equality, 1952 was a real disappointment.” Because she is beautiful and intelligent, the only thing the men can think of to do with her is either mock her when she spurns their sexual advances, or suggest she present a cookery show. In scenes familiar from Julia Childs' biographies, Elizabeth teaches women about self-worth as much as cooking. She focusses on the chemical aspects of cooking as she continues to refute social norms and expectations. There are some tough, hard-hitting moments, but it feels overall uplifting, and the bright primary colour scheme of the mid-century domestic sphere will look enchanting on the small screen in the inevitable TV adaptation. As she defends the importance and influence of women, Elizabeth points out, "Chemistry is inseparable from life – by its very definition, chemistry is life. But like your pie, life requires a strong base. In your home, you are that base. It is an enormous responsibility, the most undervalued job in the world that, nonetheless, holds everything together.”

- After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz - Mostly what we have of Sappho’s work is of fragments of writing, and this novel emulates that style with short vignettes that feel like excerpts of longer works, all relating to great female creative artists; their work, loves and lives. They work together even if they have never met in a style of sisterhood. It includes snippets of laws passed against women and miniature biographies, which lead to further exploration. Men have been cut from the stories, as women have historically been, and their absence is no great loss, as they have dominated the narrative for too long. As the author writes, “What was a man’s life but the inalienable right to verbs of action? What might Vita [Sackville-West] have become, given the transitive and a pair of sturdy boots?”

Friday, 28 July 2023

Friday Five: Books Read in July

Tuesday, 25 July 2023

You Keep It All In: A Clear Conscience

The writing style

is almost breathless, and grammar seems optional as the prose gathers pace

along with the narrative. The author constantly switches point of view so it

appears to be third-person omniscient but we are always in the mind of the subject,

blurring the lines between reality and perception. Helen’s friend Emily employs

Cath as a cleaner; Cath’s brother Damien is the murder victim of a case

investigated by Bailey, Helen’s partner; Damien was killed after a night at the

pub where Joe, Cath’s abusive husband works. There are no easy answers or

definitive source of truth; law and justice are explicitly not the same thing.

Everyone lies to a certain extent,

and no one tells the whole truth to anyone, even themselves. “We are all at

cross purposes, he thought, every one of us a little mad, each of us with a

piece of puzzle in our hands, while the truth floats up there like that big,

black raincloud.” In an attempt to feel better about one’s self-image,

characters believe their own narrative and don’t examine their motives too

closely. Helen is obsessed with home decorating, Cath smells of bleach, Emily dismisses

Cath for suspected theft of perfume – the interior renovation metaphor alludes

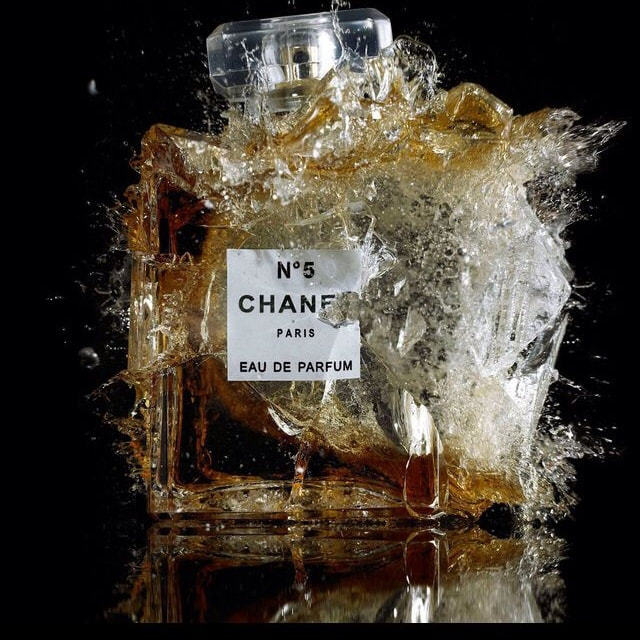

to the patina of gloss that covers cracks but doesn’t mend them. Perfume serves

a similar masking purpose. “What a terrible gift was perfume, always given by a

man to make you wear it and please him, while you stank of blackmail.”

Written

in 1994, the novel has an end-of-the-century feminism feel as the author

questions women’s roles and their need to validate themselves in society. Helen

claims to be determinedly independent and happily childfree. “I’d hate to be a megalomaniac

wife and mother. Mothers run a closed book. They shut the world out, close off anything

inconvenient, as if being mum in charge of a family is so self-satisfying, so

sanctifying, they never need have a conscience about anything else.” And yet,

she is yearning for something intangible. “It was useless pretending she was

not influenced by what she saw and read; she was not immune to the contagion of

the romantic or the desire for security purveyed by mothers and magazines…but

she did not quite know how to not want it either, or how to close her ears to

the blandishments of marriage propaganda.”