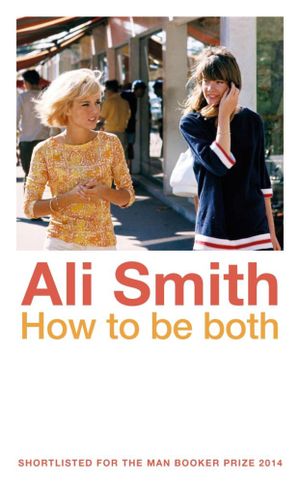

How to Be Both by Ali Smith

(Hamish Hamilton)

Pp. 371

This ambitious novel twists strands of tales together like the DNA

double helix molecule that symbolises the story. The first half concerns

Francesco del Cossa in an out of body experience – she may be dead, but she

doesn’t remember dying; perhaps this is purgatory? She is drawn to a girl who

is looking at her painting in an art gallery. The second half concerns George,

the girl from the gallery, trying to cope with the death of her mother, Carol,

who became obsessed with the unknown painter of frescoes in Ferrara, Italy and

took her daughter there to see them in situ.

The halves of the novel are both numbered One; half of the books are

printed with George’s story first and Francesco’s second. They can be read in

either order because everything is connected, and all things overlap. Sitting

in an Italian piazza and discussing the prevalence of over-painting images,

George’s mother asks her, “Which came first? The

chicken or the egg? The picture underneath or the picture on the surface?”

George says the picture underneath, of course. “But the first thing we see, her

mother said, and most times the only thing we see, is the one on the surface.

So does that mean it comes first after all? And does that mean the other

picture, if we don’t know about it, may as well not exist?”

These

palimpsests become a metaphor for life. Francesco is really a girl, but

disguised as a boy so that she can have a career as an artist. Pictures record

things past their death; they capture immortality. Carol was an art activist, “It

was her job to subvert political things with art things, and to subvert art

things with political things.”

After her mother’s death, George feels as though her

life has been split into two entirely separate halves. “That before and after

thing is about mourning, is what people keep saying.” She discovers a woman

with whom Carol had a relationship, and George stalks and photographs her every

day. She recalls how her mother used to think she was being spied upon and

‘Minotaur-ed’; was she just being paranoid? Or is this the self-enveloping

effect of time’s continuum? Both art and surveillance involve watching and

being watched, and there is always more going on than meets the eye. Carol

taught George, “Nothing’s not connected. And we don’t live on a flat surface.”

History is ever-present and the weight of all this connectivity can be

oppressive.

The novel is a complex work of meaning and metaphor: a

classic story of love and loss, told in a fresh and modern way. Both genre and

gender bending, this is a work of parallel universes, palimpsests, fluid time

and space, paranoia and mystery – almost too clever by half, and certainly

challenging, but definitely memorable.