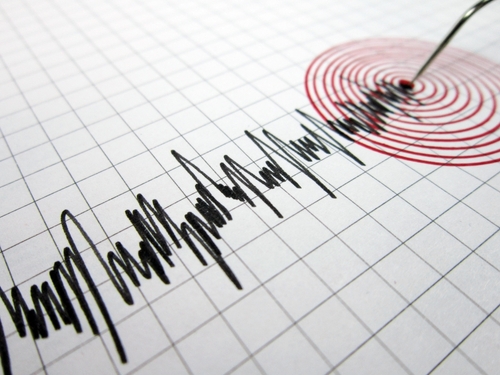

- The Richter Scale: According to Britannica.com, the Richter Scale is a quantitative measure of an earthquake's magnitude, determined using the logarithm of the amplitude (height) of the largest seismic wave calibrated to a scale by a seismograph. Originally devised to measure the magnitude of earthquakes of moderate size (magnitude 3 to magnitude 7), theoretically, the Richter scale has no upper limit, although in practice no earthquake has ever been registered on the scale above magnitude 8.6 (the Valdivia earthquake of 1960). Each increase of one unit on the scale represents a 10-fold increase in the magnitude of an earthquake. In other words, numbers on the Richter scale are proportional to the common (base 10) logarithms of maximum wave amplitudes. Each increase of one unit also represents the release of about 31 times more energy than that represented by the previous whole number on the scale (That is, an earthquake measuring 5.0 releases 31 times more energy than an earthquake measuring 4.0). Confused? Me too - that's why I leave it to the seismologists.

- British Board of Film Classification: This one seems relatively straightforward. The focus is 'to help children and families choose well by providing them with the guidance they need to help them choose what's right for them and avoid what's not'. The classifications are - U (suitable for all or 'universal'); PG (Parental Guidance); 12A (Cinema release suitable for 12 years and over); 12 (Video release suitable for 12 years and over); 15 (suitable only for 15 years and over); 18 (suitable only for 18 years and over); R18 (Adults works for licensed premises only). The classification board states on its website that it takes into consideration 'bad language, dangerous behaviour, discrimination, drugs, horror, nudity, sex, violence and sexual violence, when making recommendations. They also consider context, tone and impact - how it makes the audience feel - and even the release format - for example, as DVDs, Blu-rays and VoD content are generally watched at home, there is a higher risk of under-age viewing'. This is not just an organisation designed to spoil your fun, but one which takes seriously its responsibility to prevent the viewing public from experiencing unnecessary trauma. The problems arise because different classification boards have different standards and measures. For example, the Motion Picture Association of film rating system has several different bands (with different age recommendations depending on state) and Americans tend to censor 'bad language' much more heavily than violence.

- Magna Carta - Clause 35: Since 1215 it has been enshrined in British law that beer is served in pints (568ml equivalent) and half pints (284ml equivalent). The actual wording is, 'There shall be standard measures of wine, ale, and corn (the London quarter), throughout the kingdom.' This makes perfect sense: you know what you're getting and can compare prices with total transparency. Unlike the system in Australia of pints (which may or may not be the same size as a UK pint), pots, midis, schooners, glasses, handles, schmiddies, butchers, ponies, bobbies and sevens. These are different names and sizes depending on which state is serving your beer. It's annoying and frustrating. Beer should not be messed about like this.

- Climbing: This is so that wispy-bearded climbers can hang out in cafes drinking mugs of tea and impressing each other with their tales of derring-do and how they plan to conquer the HVD, when it stops raining. As with many areas of specific lingo, they all know what they're talking about and form a club that deliberatly excludes those who don't. The adjective grades attempt to give a sense of the overall difficulty of the climb. This will be influenced by many aspects, including 'seriousness, sustaindness, technical difficulty, exposure, strenousness, rock quality, and any other less tangible aspects which lend difficulty to a pitch.' Apparently it is an open system, which the guidebooks smugly indicate runs from 'Easy, which is barely climbing, to E11, which has been barely climbed'. Along the way we have Moderate (M), Very Difficult (VD), Hard Very Difficult (HVD), Mild Severe (MS), Severe (S), Hard Severe (HS), Mild Very Severe (MVS), Very Severe (VS), Hard Very Severe (HVS), and Extremely Severe. The last category is further broken down into sub-grades from E1 to E11, with the numerical technical grading describing the hardest (crux) move on the climb. You're welcome.

- The Beaufort Wind Scale: The Shipping Forecast is many people's favourite part of the news, sport and weather radio bulletin. As well as providing a litany of fantastically poetic names (disappointingly many of them are just lumps of rock in the sea), it also enlists the Beaufort wind force scale to deliver weather warnings. The scale ranges from 1.Calm (wind speed <1km/h; probable wave height 0m) to 11.Hurricane (wind speed 118+ km/h; probable wave height 14+m), which is highly scientific with all wind speeds measured at 10 metres above ground using meterological instruments. What is more lyrical are the specifications, which relate descriptions of likely observations on land or at sea. For example, the specification for 5.Fresh Breeze (wind speed 29-38 km/h; probable wave height 2m) is 'Small trees in leaf begin to sway; crested wavelets form on inland waters. Moderate waves, many white horses', while a 9.Strong Gale (wind speed 75-88km/h; probable wave height 7m) is described as, 'Slight structural damage (chimney pots and slates removed). Wave crests topple over, and spray affects visibility'. In case you are wondering about that previously-mentioned hurricane, it is, quite simply, 'Devastation. Air filled with foam and spray, very poor visibility.'

Friday, 29 March 2024

Friday Five: Io'll Give it Foive: Rating Systems

Tuesday, 26 March 2024

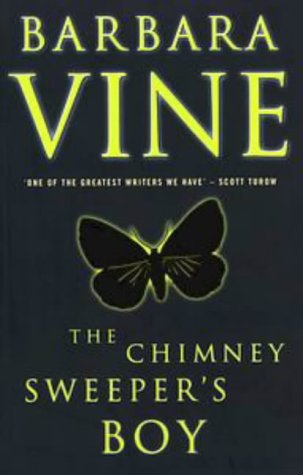

Separating Fact from Fiction: The Chimney Sweeper's Boy

As with many Barbara Vine novels, the timeframe

switches back and forth between past and present, and all the family members

are affected by the consequences of one man’s actions. Each chapter begins with

a ‘quote’ from one of Gerald Candless’ novels, allowing the author to play with

her story-within-a-story motif, as Sarah plays amateur sleuth and attempts to mine

fact from fiction. The moth on the spines of Gerald Candless’ books (and the

jacket of this novel) proves to be a ‘clue’ in the manner of an old-fashioned

detective novel, and simultaneously represents a subtle homage by Barbara Vine

to the art of cover design.

The

secrets are often to cover historic scandals, such as illegitimacy, unwed

mothers, class distinctions and homosexuality, which would not raise an eyebrow

today. She writes with sadness that such issues could lead to misunderstanding

and even murder. Another familiar trope

is the notion of blood being a metaphor for generational inheritance (both

positive and negative), while also being a vital fluid.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-626974567-defc9220866c4e679c8d244dfbb997bb.jpg)