Tanamera by Noel Barber

Corgi

Pp. 736

Tanamera (from the

Malay meaning ‘red earth’) is the saga of the eponymous house and all who live

in her, namely the Dexter family. It is a tale of a dynasty, narrated by John

Dexter, and, by extension, a novel of Singapore. Of course it is a white

colonialist’s view of Singapore and contains all the inherent classism, racism

and sexism one would expect to find in a novel written in 1981. It claims to be

both a witness to the change in the country before and after the Second World

War, and a love story, but it is so partisan that it can barely be either,

especially as the women are very poorly drawn caricatures.

The descriptions of Singapore are as viewed by an ex-pat; there are

tennis clubs and gin and tonic on the veranda. And it is hot, and full of

insects. The Dexter dynasty, and the house, was established by Grandpa Jack who

made his money through rubber (Dunlop), railways, shares in tin mines, and

setting up Raffles. The novel condenses the history of rubber and those who

control the price and the export of it. The colonialist attitudes are jarring

but not unusual: the casual racism and exploitation of the local people is

hugely unpalatable but typical of the time. This attitude of superiority extends

to gender and sexuality, as the narrator says of his brother, “even though

Tim’s sickness manifested itself in his trousers, it was the head that needed

attention.” He also refers to Tim, as “that fairy” and “a bugger boy”.

The narrator cannot write a credible female character. Julie, his love

interest, is docile, compliant and beautiful, like an ex-pat’s colonial dream

of an Asian woman. She is happy for him to take her virginity and does not mind

that she is not allowed in his tennis club or at his parties, saying demurely,

“I’ll always be yours if you want me.” Her looks and desirability to other men

raise her value in his eyes and he admits to a “fierce feeling of possession

and intimate knowledge of showing Julie off. Of course Johnnie marries and has

children with someone else, while claiming to retain undying love for Julie. He

tries to justify his actions as Julie forgives him for sleeping around and

marrying someone else because there is licence to cheat during the war,

apparently. She is light-hearted and never remonstrates with him but quotes

poetry instead in a parody of the accommodating oriental mistress.

It is unlikely that he appreciates a woman’s ability to enjoy herself

sexually; he has sex with a friend, Vicki, when they are both married to other

people and she tells him, “Every married woman secretly dreams of being raped –

by a friend of course.” Later, Julie repeats this nonsense, with the exact same

words. This dangerous fantasy of his displays a complete lack of respect and understanding.

Dramatic scenes later in the novel linger on the prurience of a gang-rape of

his wife and sister, Natasha.

|

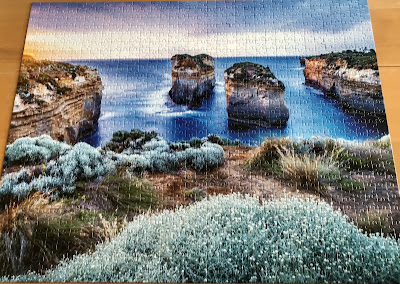

| Action at Parit Sulong, January 1942 by Murray Griffin |

There is some merit within the book, however, and it is in the description

of war and how it affects Singapore (as seen through a colonialist’s eyes). There

is a strong ‘end of an era’ atmosphere as can be expressed when viewing it in

hindsight. War, when it comes, is initially just another reason for exploitation

and profiteering, as it is seen from a distance as capitalists prepare for its

approach. Eventually Singapore falls and the war comes directly to the Dexters,

as John fights in the jungle, and there are detailed descriptions of making

bamboo bombs and the sadistic torture methods and general savagery of the

Japanese. As Barber’s reflections become more political and less personal, he

includes footnotes to historians’ writing as if to back up his fiction with

fact. He is better at understanding the big picture than individual

motivations.

As

a rambling novel of a family saga with Singapore as a backdrop, this is an

ambitious work. One is reminded of James A Michener’s Tales of the South Pacific. He couldn’t write women either and

approached the situation from a white male colonialist viewpoint, but it won

him a Pulitzer Prize in 1948 when that was the only perspective that mattered. Hopefully

times are changing.