The underworld itself - sometimes known as Hades, after its patron god - is described as being either at the outer bounds of the ocean or beneath the depths or ends of the earth. It is considered the dark counterpart to the brightness of Mount Olympus with the kingdom of the dead corresponding to the kingdom of the gods. The Underworld is a realm invisible to the living, made solely for the dead.

|

| Landscape with Charon crossing the Styx by Joachim Patinir |

The Greeks had a definite belief that

there was a journey to the afterlife or another world. They believed that death

was not a complete end to life or human existence.

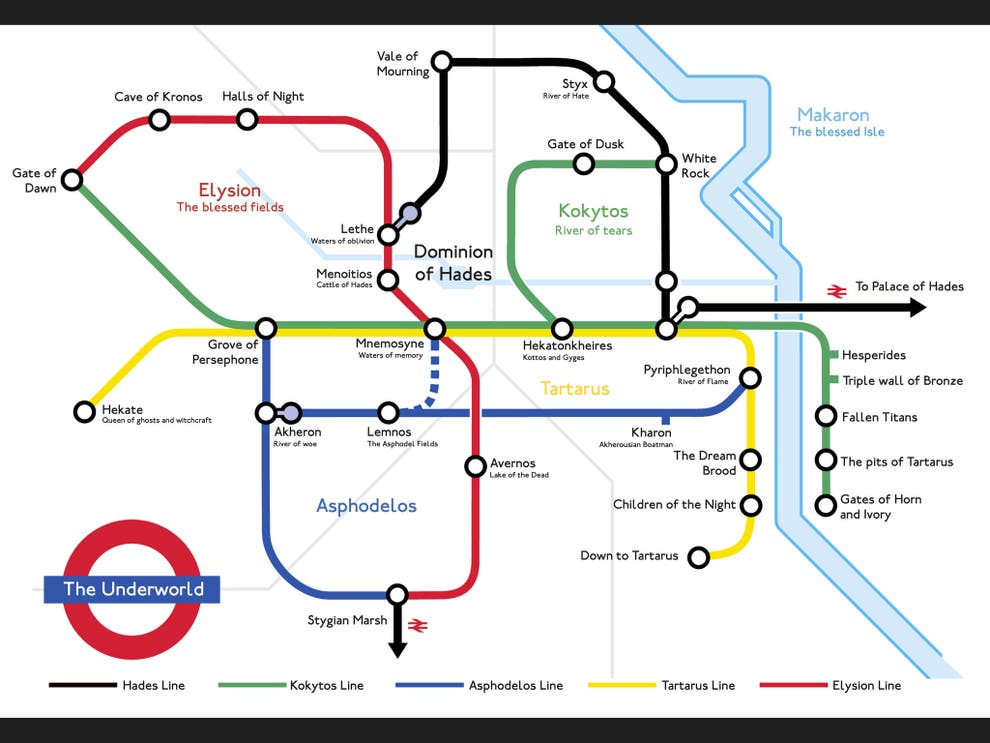

Generally speaking, the Greek Underworld can be thought of as being made up of three different regions; Tartarus, the Asphodel Meadows and Elysium.

While Tartarus is not considered to be directly a part of the underworld, it is described as being as far beneath the underworld as the earth is beneath the sky. It was thought to be the deepest region of the Underworld, ad a place where it would take an anvil nine days to reach if allowed to fall from the rest of the Underworld. It is so dark that the “night is poured around it in three rows like a collar round the neck, while above it grows the roots of the earth and of the unharvested sea.” – Robert Garland, The Greek Way of Death

Tartarus is the region of the Underworld normally associated with hell, and was the area where imprisonment and punishment was undertaken; as such it was the normal location of the imprisoned Titans, Tantalus, Ixion and Sisyphus. Zeus cast the Titans along with his father Cronus into Tartarus after defeating them. Homer wrote that Cronus then became the king of Tartarus. While Odysseus does not see the Titans himself, he mentions some of the people within the underworld who are experiencing punishment for their sins. |

| Fields of Asphodel by Brian Doers |

|

| The Waters of Lethe by the Plains of Elysium by John Rodham Spencer-Stanhope |

The idea of progress did not exist in the Greek underworld – at the moment of death, the psyche was frozen, in experience and appearance. The souls in the underworld did not age or really change in any sense. They did not lead any sort of active life in the underworld – they were exactly the same as they were in life. Therefore, those who had died in battle were eternally blood-spattered in the underworld and those who had died peacefully were able to remain that way.

Overall, the Greek dead were considered to be irritable and unpleasant, but not dangerous or malevolent. They grew angry if they felt a hostile presence near their graves and drink offerings were given in order to appease them so as not to anger the dead. Mostly, blood offerings were given, because they needed the essence of life to become communicative and conscious again. This is shown in Homer's Odyssey, where Odysseus had to give blood in order for the souls to interact with him.Hades itself was free from the concept of time. The dead are aware of both the past and the future, and in poems describing Greek heroes, the dead helped move the plot of the story by prophesying and telling truths unknown to the hero. The only way for humans to communicate with the dead was to suspend time and their normal life to reach Hades, the place beyond immediate perception and human time.