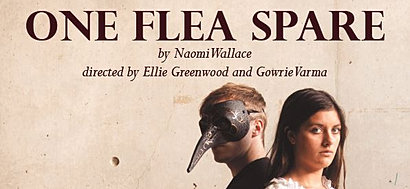

One Flea Spare

NUTS

ANU

Arts Centre, May 14-17

If

this play doesn’t win awards and accolades for the fabulous set (designed by

Gowrie Varma and Ellie Greenwood), there is no justice in this world. The

jumble of furniture and picture frames hanging from the ceiling and hammered to

the walls screams chaos. This is a world where social, sexual, political and

cultural mores are turned upside down and we are immediately plunged into this moral

morass.

If, however,

there is no justice; that would also be fitting, as inequality is one of the

major themes the play examines. In 1665 when the plague stalks the streets of London,

the wealthy couple William and Darcy Snelgrave (Andrew Eddey and Sarah Heywood)

are quarantined in their house for four weeks. On the last day of their

confinement, the house is broken into by Bunce (Lewis McDonald), a sailor, and

Morse (Cheski Walker), a strange adolescent who turns out to be the serving

girl of their neighbours. Once the guard, Kabe (George Mitton) detects their

presence, the house is sealed up for another 28 days, forcing the unlikely foursome

to live together in less than perfect harmony.

The

isolation is stifling and the silences are admirably awkward as the unwelcome house-guests

begin to learn about each other. The members of the confined quartet all give

solid performances as they tease out information and back-stories from their

characters. As in previous NUTS productions, the age of the available actors

limits the possible range of expression, but the actors playing the fifty-something

Snelgraves gave pretty fine performances considering. Darcy Snelgrave has been

physically, sexually and emotionally repressed for over thirty years, and

although Heywood plays this as more grumpy irritation than subdued longing, her

thawing is persuasive as she rediscovers the pleasure of touch and intimacy.

Her

husband is caught between trying to be the boss and wanting to explore the worlds

that Bunce has seen. Eddey portrays this dichotomy with sincerity and his

interrogation scenes are a masterpiece of cautious curiosity. McDonald,

meanwhile, imbues Bunce with authority and awareness, whether instructing

William and Darcy on physical intimacy or regaling the company with tales of

wanderlust. He adds just the right hint of intimidation when he dresses in

another man’s clothes and literally assumes the mantle of power.

As

Morse, Cheski Walker luxuriates in a childlike limpidity and her movements around

the stage are fluid and compelling. She might benefit from more variety of

tone, however, as the depiction of fey spirit child becomes a little tiresome,

and renders the screaming passion unconvincing. Similarly, Mitton could bring

more menace to the role of Kabe. His jovial cheek adds a light comic touch, but

a man who has been handed control over his past masters would surely take a more

spiteful advantage of his new-found promotion.

There

are some pacing issues in the play, which may be due to the co-direction of

Gowrie Varma and Ellie Greenwood. Perhaps having two directors rather than one

muddles the focus and prevents continuity. At times it feels as though everyone

thought someone else was providing the vision and it all gets a little lost. At

the interval, I heard several people wondering if it was actually the end, and

only the fact that they hadn’t seen the actors bow persuaded them to return to

the auditorium. Parts of the second half also flagged as though the actors were

unsure how to combine the separate movements into a cohesive symphony.

Naomi

Wallace took the title of her play from a John Donne poem in which a man exalts

in the thought of a flea mingling the blood of a pair of lovers. Of course the flea’s

ability to cross borders of sanguinity has darker consequences in terms of

disease. In the enforced isolation the characters are simultaneously saved and

damned by proximity and contact. The important moments all come through

physical transfer: transmitting gin from one mouth to another; the caress of a

body that has not been touched for 37 years; the placing of a finger into an

open wound; the angel’s breath of a child or death; the strangely seductive

handling of an orange; the thrilling fetish of toe-sucking.

This

plague affects all – the rich and poor alike – and has no respect of place,

persons nor time. Donne was a metaphysical poet; a term coined by Samuel

Johnson to describe a loose bunch of poets concerned with conceits and speculation

on themes such as politics and religion. The play’s treatment of class

disparity is apt in this context and the poetic surface belies a blunt sub-text

of growing concern over inequality as exemplified by recent riots and Occupy

movements.

Of

course, as every English school-child knows, the 1665 epidemic of the Bubonic

Plague in London was swept away by the Great Fire of 1666. The notion of purity

is strong on this stage; from the white outfits the characters wear, all the

better to show up the blood and the dirt, to the constant washing of the

floorboards with vinegar to prevent infection. The compulsory propinquity may

lead not only to epidemic outbreaks of disease, but social revolution. Wallace

seems to suggest that our contemporary plague is greed and individualism, and

only through sharing and collectivism will we recover healthy community.