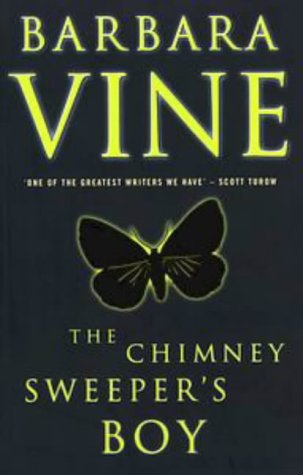

How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones

Tinder Press

Pp. 308

The

title refers to a cautionary tale parents tell their daughters not to be willful, as the child in the narrative loses an arm due to curiosity when she enters

a tunnel despite dire warnings. The message misfires when Lala (she who is told

the tale by her grandmother, Wilma) wonders whether the girl could cope without

the limb, swapped for following passion. She is cautioned, ‘but how will she

sweep the house with only one arm’? She questions whether a woman’s worth is judged

by her housekeeping, and maybe she would rather lead an adventurous life.

Unfortunately,

her adventures do not lead to happiness. The novel is set in Barbados on a

beach straight from the brochures of paradise. White folk live in tall, gated

houses, while violence, prostitution, drug smuggling, murder and other criminal

activities exist beyond their gardens, and everyone carries a gun. The police

turn a blind eye to the abuse (particularly of women) until it enters those

houses of those who go to embassies and ruin the tourist trade.

The

community is steeped in intergenerational violence and abuse. Mothers beat

their children because they do not want them to go bad and need to whip the

devil out of them; they fear that sparing the rod is the cause of the child’s

failings. Lala marries Adan, who regularly beats and rapes her, even while she

is recovering from a traumatic birth. He commits robberies to pay for his

lifestyle, which escalate to drug smuggling and murder in a sort of subplot to

the novel. His cruelty leads to a tug of war with their newborn (known only as

Baby because they have not yet decided on a name), which results in the death

of the child as she is dropped on the floor.

Girls

are routinely raped by their male relatives: Lala is the child of her mother,

Esme, and her grandfather, Carter. The young women are sent away to remove the

temptation, while the man is not considered to be at fault. Lala is made to sleep

in the outhouse to avoid her grandfather’s attentions, or how else can he

resist? Women are pursued by men. The policeman who investigates the Baby’s death

pursues Sheba and refuses to accept that she doesn’t want his protection; Adan fixates

on his ‘outside woman’ despite being married to Lala.

"A grown man cannot

help himself, she explains, in the presence of a young Wilkinson girl. This is

the way it has been for generations. It is not the man’s fault, says Wilma,

there is nothing he can do about it. It was this way with her mother before

her, her daughter and granddaughter after her. It was this way with her."

In some ways, the novel,

full of descriptive scenes and local patois, is reminiscent of those by Alice

Walker, Toni Morrison or Alan Duff. Characters struggle to connect with

community and lash out at those who seek to reinforce their culture without

understanding the roots of reggae or Rasta, merely turning gangsta. When Wilma

holds a funeral for Baby, Adan does not attend because he is wary of her

connection to culture, although he tells his friends that she is a bitch and

“he not going anywhere around her or her house.” He is alone and left behind in

the world where he has lost his local bonds.

Even

Lala is infused in her beliefs, although they may not support her – her grief,

trauma and post-partum depression are explained in superstition. “She is

convinced also that supernatural beings are conspiring on her daughter’s behalf

to make her understand that she will pay for her part in her death.” She fears a

“wicked duppy” is playing tricks on her, putting cans of formula in the

cupboard, although she knows she has thrown them all out, sprinkling the scent

of baby powder in the house, and “It is this duppy, or another, equally

malevolent, who infuses the peculiar sound the paper bag of flour makes when

she is making dumplings and it hits the floor with the same sound she heard

when Baby was dropped.”

Reviewers

have called the book unflinching, claustrophobic, pitiless, and relentless. Focussing

on murder, abuse, a violent marriage and the death of a baby, it is certainly

no light-hearted tale, but there is a slight glimmer of hope towards the end,

and it is ultimately compelling. It is exquisitely constructed, with flashbacks

to flesh out the characters and the pathways that have led them to this Barbadian

beach, and it is a great achievement for a debut novel.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-626974567-defc9220866c4e679c8d244dfbb997bb.jpg)