At the National Gallery I take a detour to the Sixteenth-Century paintings to indulge my soft spot for Titian, now I feel I have an Italian connection with him. En route I am impressed by El Greco’s The Adoration of the Name of Jesus (1578) – a small canvas packed with detail and symbolism.

Joachim Beuckelaer also seems to know a thing or two about symbolism, with his Four Elements series (1569) which represents said elements with seductive images of market produce. A small scene from the life and teachings of Christ lurks in the background of each picture – he is considered one of the earliest and most accomplished masters of the fusion of the New Testament narrative with everyday life (Beuckelaer that is, not Jesus - although he could probably stake a claim too). These pictures were made quickly with bold and broad brushstrokes. Beuckelaer reveals himself as a skilled colourist – repeating and echoing colours and patterns in order to guide the viewer’s eye across his compositions.

Water features the stallholders with seafood, while Christ in the background appears to the disciples and fills their empty nets with fish. In Earth vegetables tumble from a basket and cascade towards the viewer – the holy family cross a bridge in the background.

Poultry and other skinned haunches of meat are the foreground focus of Fire – a still life with a dramatic construction. Christ is seated with Mary and Martha in the background. The background image in Air is of the prodigal son parable, while the market scene is one of fowl and rabbits (both dead and alive) framed by piles of eggs and stacks of cheeses.

Titian’s An Allegory of Prudence (1565-70) has three faces which represent the past, present and future. Apparently the triple-headed wolf lion and dog stood for prudence in sixteenth-century art and literature – ‘learning from yesterday, today acts prudently, lest by his action he spoil tomorrow’. In his Portrait of a Man (1510-20) the man in question appears to have just turned to face the viewer. His elaborate blue sleeve dominates the picture, protruding over the parapet to enhance the 3D quality of the image. Bacchus and Ariadne (1520-3) is a celebrated work of classical mythology, but I can’t get over the fact that Bacchus looks like he’s bowling down the wicket.

My brain is now full of images, light, perspective and composition. Placement and framing is of utmost importance in these paintings but also, I realise in my photography and, even as I am sated with culture, I am refreshed with themes and ideas.

Moving on to ‘Painting Out of Doors’ at The National Gallery, the room is lined with panels by Jean Baptiste-Camille Corot depicting changing light through the trees and sky over the space of a day, with small figures for emphasis and perspective. The next room is ‘Manet, Monet and Impressionism’, and now we are into more familiar territory. We have Renoirs and Berthe Morisot’s Summer’s Day (1879) where two women relax in a boat on a river. Edouard Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian (1867-8) is a reconstructed canvas. It’s pretty big and shows the firing squad preparing for their mission – all we see of the victim himself is his hand.

Claude-Oscar Monet’s The Beach at Trouville (1870) proves his open-air style. In the sketch of his wife and a friend, grains of sand and shell are embedded in the paint surface. There is also one of his Gare St-Lazare (1877) paintings – of which there are twelve painted from the same spot, capturing the light at different times of the day.

A woman delivers beer to men watching a dancer on stage in Edouard Manet’s Corner of a Café-Concert (1877-80). Her attention is diverted by something off to the side of the canvas and she is looking in completely the opposite direction from everyone else – we wonder what has caught her eye.

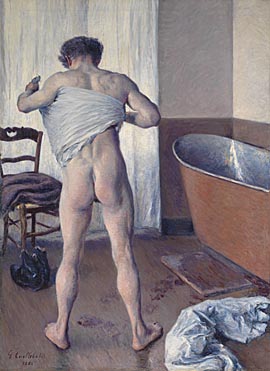

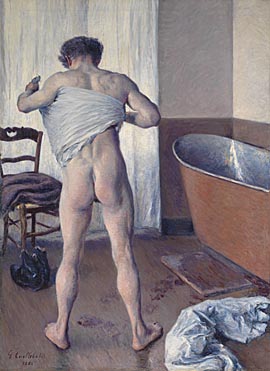

Gustave Caillebotte’s A Man at His Bath (1884) is a fascinating study, as I realise there aren’t so many paintings of the male figure – it was considered not as acceptable as images of naked women. Interestingly, when I try to buy a postcard of this painting, there are none for sale. Plus ça change... The catalogue notes explain, ‘The male nude is a relatively infrequent subject in late nineteenth-century painting. The matter-of-fact presentation of the figure here, drying himself after emerging from the bath and leaving wet footprints on the floor of his Parisian apartment is particularly rare. Also unexpected is the painting’s larger-than-life scale.’

I like Alfred Sisley’s View of the Thames: Charring Cross Bridge (1874), with the boats on the water framed by the city sky-line, all rendered with his short stroke technique and ‘nervy brushwork’. Camille Pissarro’s Portrait of Felix Pissarro (1881) is a portrait of his third son when he was seven years old (the son, not the artist) wearing a red beret against a green background – it’s a great colour contrast.

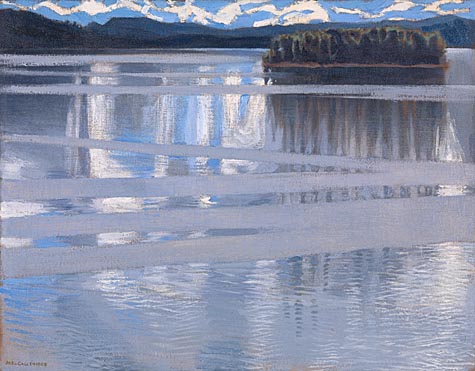

We have now move on to ‘Beyond Impressionism’ apparently, with Pissarro, Seurat and others who adopted the pointillist style – notably Alfred William Finch who paints an austere scene in The Channel at Nieuport (1889) in which the water and sky meld almost imperceptibly into one to exude an atmosphere of emptiness and silence. Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Lake Keitele (1905) is a more naturalistic painting of a lake just north of Helsinki.

Theo van Rysselberghe uses simple colours to big effect in his pointillist homage, A Coastal Scene (1898). George Seurat’s Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp (1885) is a study of a promontory with birds and boats in the background. Even the borders are done in his dotty discipline.

I am reunited with Pierre Auguste Renoir’s At the Theatre (1876-7). I love this painting – the isolation of the young girl and her chaperone in the theatre box are the focus rather than the action on stage. Camille Pissarro’s shimmering brushwork and eclectic use of colour are evident in The Little Country Maid (1882) and The Pork Butcher (1883).

Paul Cezanne is also a master of colour and he broke away from the Impressionists with his use of colour rather than light to convey form. Examples include An Old Woman with a Rosary (1895-6); The Painter’s Father, Louis Auguste Cezanne (1862); The Store in the Studio (late 1860s) and Self Portrait (1880) in which he experiments with geometric structure and blocks of colour. Bathers (1888-1905) is outlined in blue to accentuate the serenity of the scene.

This room also contains work by Edouard Vuillard – The Earthenware Pot (1895) contains dots and dashes and such deep reds and bright flowers that the image of women sewing is like a lacquered vase itself.

Naturally Van Gogh is represented here, by Van Gogh’s Chair (1888) and Sunflowers (1888), but also by the less familiar Long Grass with Butterflies (1890), A Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889) and – a new favourite of mine – Two Crabs (1889).

I hear people with their banal comments on art appreciation: ‘I just love pointillism; it’s so aggravating’; ‘She must have sat still for hours’; ‘Fantastico!’; ‘That’s amazing, but where would you put it in your house?’; Parent to child – ‘His paintings are worth millions.’ Child – ‘Really?’ Another parent to another child – ‘Can you see the sunflowers?’

In the ‘Degas and Art around 1900’ room there are (obviously) pastels by Degas of dancers, ballerinas and peasants. I particularly like Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando (1879) as she spins from her teeth, high in the air, unsupported by anything but a rope. We also have Klimt, more from Edouard Vuillard, and Surprised! (1891) by Henri Rousseau. By placing the trees along a diagonal axis he has conveyed a sense of wind in spite of the painting’s static and naive style. (‘See the tiger?’)