Fled is based on the

life of Mary (Dabby) Bryant, the woman behind one of history’s most daring

escapes. Sentenced to seven years transportation to Australia, she escaped from

the colony and sailed over 3,000 miles for 66 days in a stolen open boat with

her husband, two children and other companions to West Timor (Coepang as it was

then called). Here she was discovered, arrested and returned to Britain to be

incarcerated until she was taken up as a cause célèbre by James Boswell who set

her up in a house and sent her a stipend after she returned to Cornwall. In an

Author’s Note, Meg Keneally stresses that this is a work of fiction, which is

why she has changed some elements of the story, including names of the

characters – Mary Bryant becomes Jenny Trelawny, later Gwynn after marrying Dan

Gwynn.

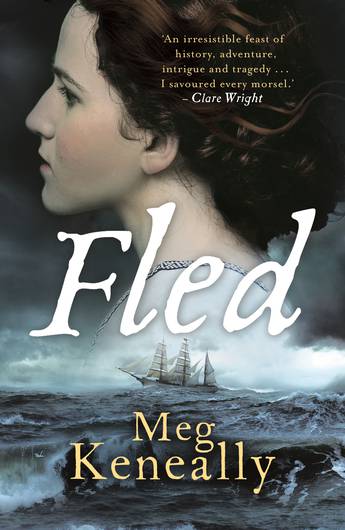

The first part of the novel

concerns Jenny’s route to crime and the highway robbery for which she was

transported to the other side of the world. There is a detailed account of that

trip on the Charlotte, on which she conceives

and after which her daughter is named. She befriends Captain James Corbett,

whose character is based on that of Watkin Tench, who tells her, “We don’t need

to remake Newgate on the other side of the world. Well, I imagine there will be

a guard house, or something like it. I’m sure that not everybody has left their

criminal disposition back in England. But the entire place is intended as a

prison. We’ll have no need of walls for the most part, it is to be hoped. We’ll

have the ocean.”

|

| The Charlotte at Portsmouth, May 1787 from Frank Allen's The Ships of the First Fleet |

Life in this colony is brutish

and cruel, as it is intended to be, in a land that must seem upside-down. The

triangle that is used for the floggings is “an ominous symbol, a profane and

subverted trinity.” To save herself from rape and degradation by the male convicts

and soldiers, she marries Dan and has another child, Emmanuel (these were the

real names of Mary Bryant’s children). Married couples are given separate

quarters but others, jealous of what they perceive to be her advantages, strive

to bring her low. When their actions result in Jenny being expelled to the

women’s camp, she reflects, “While space was the only blessing this colony

provided in abundance, it was one of the many denied to the hut convicts. Jenny

now lived in a place of wails and screams and sobs and fights, of stench upon

stench, of dangers buried in innocent conversation.”

From the moment she lands in Botany

Bay, Jenny knows she wants to leave, and it soon becomes apparent that their

best chance of survival is escape. Food is scarce, supply ships are absent, farming

is in its infancy, and provisions are rapidly dwindling; making theft of food a

hanging offence and starving to death a distinct possibility. Perhaps if the

settlers had collaborated with the local people they might have had better

chances of survival, but there is limited interaction between the white settlers

and the Indigenous tribes. Jenny encounters an Aboriginal woman who shows her

what leaves to chew or to brew to avoid scurvy. Although these are plentiful,

Jenny guards this knowledge as currency, as she does when the Indigenous people

take her fishing and share their methods with her.

Questions have been asked as to

why Mary Bryant would risk a journey for herself and her children on the ocean

and potential drowning. As well as starvation, the new colony is rife with

disease (particularly smallpox) and the dangers to the women convicts are

manifold. “Emmanuel’s death at sea is a possibility. His death here is nigh on

certain.”

|

| 1930s era illustration of the convict escape |

Eventually she returns to her family in Cornwall. She had been afraid of their reaction, but they are thrilled to see her and welcome her back, so the story has come full circle. This is one of the bits that the author has invented, but it makes for a satisfying conclusion. Mary Bryant’s adventure is a fascinating story and, although she has changed the names to compensate for lack of certain facts, Meg Keneally has told it with drama and compassion.