The Museum of Tropical Queensland (or Queensland Museum Tropics - institutions tend to change their name over the years, but only slightly; just enough to cause confusion) is a spot in Townsville where I went to visit what purports to offer 'a deep dive into the collections of Queensland's tropical paradise from pristine rainforests to the magnificence of the Great Barrier Reef and the ocean's bountiful treasures.'

The Great Gallery is dominated by a replica of the HMS Pandora, the ship sent by the British Admiralty in 1790 to capture the Bounty and her mutinous crew in Tahiti. Captain Edward Edwards (son of imaginiative parents) had one mission - to bring the 'pirate villains', as he called them, to justice. Armed to the teeth, and heavily laden with provisions, HMS Pandora set sail under Edwards' command in 1790. Expecting to capture the Bounty, Edwards took twice the crew to sail both Bounty and Pandora home.

After almost five months of travelling, Pandora arrived in Tahiti. Over several weeks, 14 mutineers who had returned to Tahiti surrendered or were caught. Another two were declared dead.

Edwards spent the next three months searching the South Pacific in a fruitless hunt for the remaining nine mutineers. Little did he know, Pandora had originally come within half a day's sail of these mutineers before ever reaching Tahiti. Fletcher Christian and eight other men found refuge at Pitcairn Island before burning and sinking Bounty. They lived there undetected until 1808.

By August, Edwards was running short of supplies, had lost 14 of his own men and still not found any more mutineers. Feeling the loss of his crew and fearing a mutiny of his own, Edwards headed home.

Fourteen mutineers were shackled to rows of leg irons in a cramped, dark box. It wasn't high enough to stand upright; the toilet was a bucket; movement and fresh air were lacking. Constant heat created sweat pools on the floor and continuous filth brought maggots and rats to live with them for three months.

This was the treatment of Edwards' 'pirate villains'. They were imprisoned on the ship's stern in a purpose-built jail they dryly called 'Pandora's Box'. According to the ship's surgeon, the prison was airy and healthy, 'the most desirable place on the ship'. Clearly the reality was far worse.

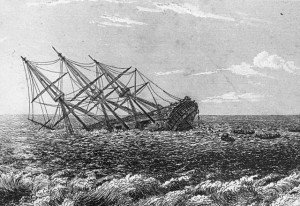

Tragically, on her return journey in 1791, Pandora hit the Great Barrier Reef and sank, taking 31 crew and four mutineers to their grave. As the ship went down, 13 prisoners escaped the box thanks to last minute efforts by the Boatswain's mate, Moulter. One mutineer, Henry Heildenbrandt, could not be freed as Pandora sank, condemning him to an eternity in Pandora's box.

|

| The wreck of the Pandora |

Reeling from the horrific death of their friends and the loss of Pandora, the 99 survivors - 89 crew and 10 mutineers - recovered at a sandy cay near the wreck site. Their trials weren't over yet. They still had to navigate 2,100km to Timor before finally making it back to England in mid-1792. Here, seven of the ten remaining mutineers were acquitted, while three were convicted and hanged.

Pandora remained undiscovered for 186 years and today, objects recovered from the wreck are part of the Pandora exhibition at the museum. Among these objects are nearly 200 essence of spruce pots.

For hundreds of years, scurvy was the most feared of all diseases at sea. It affected all people in all climates, without apparent cause. By the time of the Pandora's voyage, scurvy had been linked to a lack of fresh fruit and vegetables. However, it was not until the early 20th century that Vitamin C was identified as vital to preventing the disease.

Captain Edwards made sure the Pandora was reprovisioned with fresh foods as often as possible. Anti-scorbutic foods such as sauerkraut (pickled cabbage), wort (a drink made of malted grain) and a thick cordial known as 'rob of lemons' were also carried. The Pandora's log records that '380 pots of essence of spruce' were loaded. Contemporary records suggest that the essence may have been combined with molasses, yeast and water, allowed to ferment for a few days and then drunk as a beer.

About 40,000 litres of beer, wine and spirits were stored in barrels and bottles. A sailor's daily allowance of beer was one gallon (4.55 litres). Drinking was a way of life on board and was tolerated, but if it caused a sailor to neglect his duties or disregard the ship's rules, he could expect a flogging as punishment.

The calorie content of beer was a much-needed source of energy for sailors performing a hard day's work. Off-duty hours could be spent socialising or 'yarning'. If the beer ran out, hops, malt and water were available for brewing. Watered-down wine or rum (grog) was issued instead of beer. Officers drank as often as the sailors. They were known to reward deserving sailors under their command with a drink or a bottle from their private stores: usually port, gin or Dutch gin (jenever).

|

| Admiral Edward Vernon by Thomas Hudson |

The word 'grog' derives from a nickname given to Admiral Edward Vernon, who was called 'Old Grog' because he always wore a coat made out of grogram (grosgrain). He was very unpopular after his decision to curb drunkenness aboard navy ships by watering down the rum ration. The sailors promptly named this watered-down drink 'grog'.

The crew was divided into messes. These were groups of 4-12 men who usually worked together as a team. The core of each mess was a table, hinged at one end and suspended from the deck beams at the other. Meal times were not interrupted, unless in exceptional circumstances. It was a time of much needed rest and relaxation. A 'cook of the mess was appointed each week. He collected food from the gallery, cleaned the eating utensils, and kept the mess in order.

The term 'chewing the fat' originally described the crew talking and grumbling while sitting in their mess, eating their toughened salt meat. An ordinary seaman's diet typically consisted of cold oatmeal porridge at breakfast, salted beef or pork with ship's biscuit or bread at lunchtime, and a small piece of cheese, butter or oil with more biscuit in the evening. 'Portable soup', a hard meat extract, was added to the boiled meat. Additional foods such as vinegar, mustard, onions and sauerkraut were sometimes served. When available, fresh fruit and vegetables supplemented this diet. The beer ration amounted to over four litres a day and was a substitute for water.

The sandstone dripstone was sometimes described as a 'water purifier' although it could not remove bacteria or salt from salt water. It was effective in removing large particles, such as algae and debris, from fresh water collected from rivers or streams, or from water stored in barrels. The dripstone was placed above a barrel. Water decanted from a cask would slowly filter through the porous sandstone into the barrel. This water was probably reserved for use by the captain or the officers. The large volume of water stored in the hold was used for cooking rather than drinking. Although seamen were able to drink water from a large barrel placed on deck, they preferred to drink beer, or water mixed with wine or sometimes with rum.

Many of the artefacts found on the wrecksite belonged to officers or petty officers who aspired to higher social status. Particular objects may have been acquired by officers to demonstrate their status as gentlemen.

Royal Navy officers in the 18th century usually joined as midshipmen or captain's servants. Most were sons of professional men or the gentry. After at least six years' service they sat their lieutenant's exam to become a commissioned officer.

Officers were expected to behave like gentlemen. They had to follow an unwritten code of behaviour, master skills such as navigation, and possess leadership abilities. A gentleman owned objets de virtu, such as a gold and silver fob watch with an ornate chain or an étui (small case) with writing implements. When travelling, he would also have a portable writing desk, in which he kept his journal, papers, writing materials, and possibly a signet or name stamp.

Preparations for a long voyage were expensive. An officer had to provide his own navigational instruments, bedding, cabin furnishings, crockery and glassware, uniforms, clothing, linen, toiletries and a private supply of provisions and beverages.

Many Polynesian artefacts and natural specimens have been found buried in the shipwreck. They were acquired by the officers and crew as the Pandora sailed across the Pacific. These objects have now become one of the most important collections from traditional Polynesia. The importance of these finds is that none of them could have been in use in Polynesia any later than 1791. They come from a time before any lasting European influence on Pacific cultures.

Eighteenth century European voyages to the South Seas stimulated intense public interest back at home. Collectors were keen to obtain exotic objects (artificial curiosities) and animal and plant specimens ('natural curiosities') from the newly discovered lands. Dealers in 'curiosities' were often seen at the waterfront waiting for returning ships.

Sailors on Pacific voyages used objects such as metal tools, nails and glass beads as barter for 'curiosities' with local inhabitants. Surgeon Hamilton's voyage account records the Pandora's crew trading for 'curiosities' wherever they visited. The Polynesian items recovered from the Pandora are a unique record of 18th Century Polynesian technology and the natural environment.

The adzes on display were made from volcanic rock and originally attached or hafted to a wooden handle with plaited coconut fibre. The 25 basalt adzes excavated from HMS Pandora provide insight into the movement of objects in the 18th century. The captain's log links the stone tools to specific regions in the Pacific Islands where Pandora stopped on its journey, and the archaeological assemblage shows evidence of trade between the crew and the locals.

By looking at the shape and form of the tools, mid 20th-century typological analysis has identified the certain types of adzes originated from different island groups. This tells us more about where the stone adzes from Pandora were collected and also suggests that the stone was sourced and the tool manufactured in the same place. Most adzes from Pandora have consequently been linked to the Society Islands, where the crew spent many weeks during the voyage. The remaining adzes are thought to be from Aitutaki and Palmerston Island. Notably, one style of adze appears to originate from Tubuai, an island visited by Bounty but not Pandora.

These Polynesian shells were found inside the shipwreck. They were probably collected by some of the Pandora's crew to take back to England. Shells were popular with sailors. They were simple to collect from beach or reef top and were easy to store.

This cabinet shows fishhooks made of pearl shell (possibly collected in Tahiti), three-piece fish lures made from bone and pearl shell (possibly collected in Tonga),a limestone sinker and pieces of cowrie shell attached to a stick which were used to attract and capture octopus (possibly collected in Tonga or Samoa), and two-piece fish lures, lure shanks and trolling hook points, made from pearl, and all possibly collected in Tahiti.

I understand the adage of taking only photographs and leaving only footprints, but I also admire these collections and stoires which reveal to us some of the ocean's treasures, and the motivations of those who sailed upon them.