Impressionist Gardens

Royal Scottish Academy Building

31 July - 17 October 2010

The Impressionists were interested in the pleasure of the here and now, and to them gardens symbolised relaxation, recreation, innocence and light. They were inspired by Corot’s sun-dappled canvases, capturing the effect of light through the trees, the details of raindrops on roses in Simon Saint-Jean’s The Gardener Girl (1837) and Delacroix – his casually arranged arrays of dahlias and other cut blooms are the spiritual forebears of Monet’s and Gustave Caillebotte’s paintings of dahlias growing in their gardens at Argenteuil and Petit-Gennevilliers.

I love Spring (1804) by Jean-François Bony: the painting of spring flowers relegates the statue of a warrior goddess in the background to a secondary role. The focus is on the foreground lilacs, hollyhocks, roses, poppies, delphiniums, striped parrot tulips – the very flowers of my wedding bouquet.

|

| Still life can be stylishly scruffy - Flowers in a Vase by Pierre-Auguste Renoir |

Gardens and flowers were not formal constructs. Pierre Auguste Renoir’s Flowers in a Vase (1866) is a reminder of a stroll in the fields – wild flowers (corn poppies; chamomile; ragwort; cornflowers; rampion; wild parsley and Spanish broom) are stuffed into an earthenware vase. More prosaic vegetables are admired in A Flemish Kitchen Garden (1864) by Henri de Braekeleer where giant cabbages provide colour and a subtle poetry in the harvesting in the kitchen garden.

Gardens were outdoor studios; places in which to capture the effects of sun, shade and seclusion. They could be the theatre of fashion or tranquil meditation. Thomas Couturés’ The Reading (1860) depicts a lady engrossed in a book and oblivious to her surroundings. Charles-François Daubigny was commissioned by Napoleon III to paint The Cascade at Saint-Cloud (1865) which is a grand, formal work but, once again, the historic monuments are relegated to the background. Similarly, John Singer Sargent takes a thoroughly Impressionist delight in the incidents of modern life in The Luxembourg Gardens at Twilight (1879) which features children sailing their boats despite the lateness of the hour, and a well-dressed couple strolling at the centre.

|

| Contemplative colour in Frederick Childe Hassam's Geraniums |

Gardens are for sewing, playing croquet, quiet contemplation and drinking tea. And there is always room for colour. Frederick Childe Hassam painted red geraniums, watering cans and his fair wife engaged in embroidery in Geraniums (1888-9). James Tissot tinged his autumn leaves around the reflective pool with sadness in Holyday (1876). Gustave Caillebotte kept flowers in dedicated beds in his garden (unlike Monet’s mixtures) allowing him to paint studies of nasturtiums and, my favourite, Daisies (1892). Edouard Manet’s The House at Rueil (1882) is also grouped in this collection.

Napoleon III’s ambitious programme of parks and gardens was continued by the Third Republic which came to power in 1871. The new and revamped gardens provided perfect opportunities for the Impressionists to paint ‘en plein air’ but Monet and the other Impressionists preferred the city’s old, historic gardens with spreading trees and natural features. Léon Frederic’s The Fragrant Air (1894) depicts an innocent child sniffing ephemeral blooms redolent of death and mortality.

|

| Lotus Lillies by Charles Courtenay Curran - the object of his affections |

Charles Courtney Curran’s Lotus Lillies (1888) is a sublime painting of his bride, Grace Winthrop, haloed by a green parasol as she floats in a boat across Lake Erie in Ohio. She is the finest of the lotus blossoms (symbols of purity and tranquillity) and the clear object of Curran’s veneration.

|

| Skaters in Frederiksberg Gardens - Paul Gaughin |

Also included here is Paul Gauguin’s Skaters in Frederksberg Gardens (1884) – a striking action portrait in which the vivid reds and greens of the fallen leaves emphasise the coldness of the ice, in stark contrast to his more familiar sun-drenched views of Tahiti.

James Ensor’s The Garden of the Rousseau Family (1885) and Charles François Daubigny’s Orchard in Blossom (1874) highlight kitchen and vegetable gardens with no ostensible aesthetic purpose, but the abstract design of flat zones of green bisected by paths and walls offers visual impact. Arthur Melville’s A Cabbage Garden (1877) and Alfred Sisley’s The Fields (1874) share the same theme – the latter’s market gardens full of rows of vegetable crops mature with the seasons, while the old spreading tree in the corner indicates continuity.

The Artist’s Garden at Eagny (1898) by Camille Pissarro shows his wife planting seeds. The leaves and flowers shine like jewels while the house behind implies the family for whom she is preparing this food. The Portrait of Karl Nordstrein (1882) by Christian Krohg of a pointed-bearded gentleman standing at a window looking out at a market garden draws our gaze from across the room. We want to see what he’s looking at.

|

| The Cote des Boeufs at L'Hermitage by Camille Pissarro |

Is winter the hardest season to paint, with its suggestion of bleak hibernation? Alfred Sisley’s subtle harmony of restrained colouring integrates the snow into the scene as a natural part of the design in Winter at Louveciennes (1867). The scudding clouds, fresh breeze and tall poplars enhance the motionless figures of The Côte des Boeufs at L’Hermitage (1877) by Camille Pissarro.

Apparently Impressionism begins again with a completely new phase in the 1890s. Henri Martin offers Garden in the Sun (1913) in which sunlight from outside floods in like a powerful unrestrained tide of pink, yellow and cream. In The Pergola (1912-13) shows the last fruits of summer as Marie Enger adds a hint of autumn chill through grapes and red and golden gourds surrounded by withering vine leaves.

Bright colours return to the fore with Theo van Rysselberghe’s Fountain in the Park of Sans Souci near Postdam (1903). Clearly heavily influenced by Seurat’s pointillism, the technique of contrasted dots or flecks of colour display the refraction of a fountain into rainbow droplets by the afternoon sun. In The Rainbow (1896) we are invited to see a pristine garden through the eyes of his wife and son. Spring bulbs, reddish-brown flower pots, shimmering perblossom, red and blue outfits, and the red roof and blue sky combine to echo the colours of the rainbow, creating a larger harmony.

|

| Gustav Klimt's Italian Garden Landscape illuminates the room |

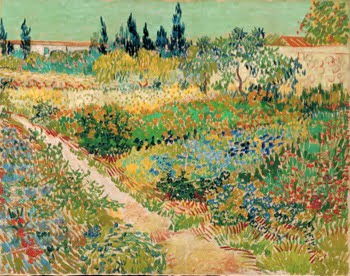

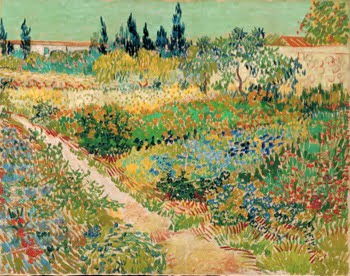

In the final room it is as though the best have been saved until last. Gustav Klimt’s Rosebushes Under Trees (1904) and Italian Garden Landscape (1913) are sumptuously rich and decorative with varied textual brushwork that illuminates the room. Vincent Van Gogh is represented by The Garden with Path (1888) and Undergrowth (1889).

|

| The Garden with Path - Vincent Van Gogh |

The first is a rich variety of jabs, zigzags and short stabbing strokes to evoke the flowers, vegetables and olive trees as they shimmer in the hot southern sun. The second was painted in the grounds of the sanatorium to which he admitted himself. The grasp of the ivy on the oak represents the grip of mental illness on his mind, but the glimpses of sunlight between the shadows suggest hopes of better health.

Naturally, there couldn’t be an exhibition of Impressionist Gardens without the inclusion of Monet’s water lily pond, and there is a shining section of wall that displays some stunning examples. Him Outdoors sighs, ‘He really was the master, wasn’t he?’

|

| Saving the best until last - Claude Monet's The Water Lily Pond, 1904 |

The largest retrospective of Monet's art since 1980 opens in his home country with an exhibition in Paris this month - expected to break all gallery attendence records. With the excessive wishy-washy reproductions it is sometimes easy to overlook the man's artistic genius (a sentiment felt especially by the French who until now have regarded arguably their most famous painter as one who created daubs for American tourists); until you stand in front of one of his canvases and feel overwhelmed by light and colour.

Displays of art can often leave you satiated as you emerge from some stuffy museum, but this invigorating exhibition is like a breath of fresh air.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)