The following are short reviews of the books that I read in January 2014. The marks I have given them in the brackets are out of five.

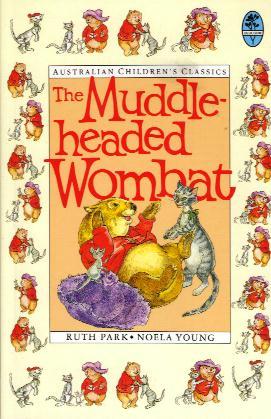

The Muddle-Headed Wombat –

Ruth Park & Noela Young (illust.) (4.7)

This Australian children’s classic is an utterly

delightful tale of a wombat and his adventures with Mouse and Tabby, his

second-best friend. They go to school, visit the circus, have holidays by the

sea and build a treehouse that collapses in a storm. Frequent squabbles

punctuate their escapades, as they have many differences, but they always make up

as they realise the value of friendship.

Wombat is muddle-headed because he is a Wombat. He

mixes up words and can’t count past four – “He runs out of paws, that’s the

trouble” – but he likes to be helpful although his favoured solution to a

problem is to sit on things. Similar to Pooh Bear he is not bright although he

has inimitable logic, such as when he eats a packet of chalk but not the green

because “it might taste like spinach and I don’t like spinach.” He is good at

digging and seeing in the dark and is very loyal and loves his friends, which

in turn makes him loveable.

Mouse is fastidious and house proud, always cleaning

things, preparing meals (pancakes for Tabby; snails for Wombat; and mosquitoes

for itself) and polishing its spectacles. Mouse is also sentimental and cares

for things and people, particularly the grey tabby cat whom it adopts because

“He was skinny and miserable and he had a peaky little face with big ears. He

wore a bright red bow tie, but anyone could see it hadn’t been washed and

ironed for weeks.”

Like many cats, Tabby is vain and thinks he is

handsome, while he also claims to be frail and delicate, mainly to get out of

hard work. He is very good at building things, however, such as a caravan and a

treehouse and is also remarkably resilient, surviving being sucked into a

carpet cleaner, dropped from a great height while performing as a puppet, and

accidentally shaken into a stream, not to mention being sat on by Wombat.

Noela Young’s charming illustrations add to the humour

of the stories and caricature the animals highlighting their best and worst

traits. They regard themselves as a family and they constantly attempt to adapt

to living with each other while retaining their individuality. The tales are

equally diverting and reassuring and were loved by both the adults and the

children at holiday story-time.

The Voyage –

Murray Bail (3)

Murray Bail is a fan of the experimental novel. Some

may call it modernism; others stream-of-consciousness; still others pretentious

nonsense. The eponymous voyage is the journey taken by ship of Frank Delage on

his return from Vienna to Sydney. He travels to Old Europe to seduce the

musical community with his new piano, which has a radically clear sound, but he

fails to generate much interest.

An appallingly bad salesman or promoter, he

blames others for his shortcomings even though he achieves an introduction to a

modern composer through a rich and influential couple (the Schallas). He falls

for the mother, Amalia, but returns to Sydney with the daughter, Elisabeth. The

trip from the New World to the Old and back again proves ultimately

meaningless, as his influence is superficial and his piano sinks without trace.

On the ship, Delage talks to the other passengers and

hears their stories, while reminiscing about his own experiences. These stories

overlap and interweave, often in the space of a sentence. An absence of

chapters, paragraphs that extend over several pages, and constant switches in

time can become wearisome.

Delage imagines that the problem is with Vienna, which

he accuses of being stuffy and resistant to change, rather than his piano and

he wonders frequently why he didn’t try Berlin instead. It’s not that he

prefers anywhere else: he is equally scathing of Perth, “which has a history of

visitors setting foot on the place and immediately wanting to turn around, a

reaction which continues to this day” and Sydney, where he attacks the

architecture of the iconic Opera House.

In fact, it is difficult to find

anything that Delage does like in this whingeing barrage of bitterness. Everything

is linked in his mind, which flits about with the attention span of a flea. He

has an opinion on everything, although it is rarely a positive one. From

central heating to diplomats, he barely has a good word to say about anyone or

anything. He even criticises smiles, which are insincere and “have no meaning”.

The only conclusion to be drawn is that Bail fears he

has been treated unfairly by critics, as he reserves his strongest vitriol for

this profession. He (or his central character; the constant asides are

inseparable from authorial intrusion) claims that modern novels display a lack

of invention and are “more and more an author’s reaction to nearby events, a

display of true feeling.” He tells the reader, “We should not be disapproving

of repetition... It is necessary”.

It may be necessary, but it isn’t

necessarily interesting. With his interconnections, he sees music as an analogy

for literature – exactly what he accuses critics of doing. “All art, he said,

including the playing of pianos, was imperfect... As listeners, we actually

want an imperfect result. It is human, and therefore closer to human

understanding. Otherwise, it is beyond understanding.” Not so. I understand

this; I just don’t like it.

The Rover – Aphra Benn (3.5)

Set in Naples in the world of carnivals, masquerades,

fantastic costumes, fights in the dark, disguises, and mistaken identity this seventeenth

century comedy would provide a real stage spectacle. Otherwise known as The Banish’d Cavaliers, the play contains

all the characters, staged fights, lack of didactic politics and witty dialogue

to suit the Reformation times. Aphra Behn famously worked as a spy for Charles

II but turned to playwriting when she lost her income as he refused to pay her

income.

The rules of morality are different in Naples from in

England, which is fortunate as the play is largely about sexual encounters,

with a few racist stereotypes thrown in. The eponymous rover, Willmore, has

been away at sea and is very horny now that he is on terra firma. ‘I’m glad to

meet you again in a warm climate where the kind sun has its godlike power still

over the wine and women. Love and mirth are my business in Naples.’

The play is full of flirtation, jealousy, wit,

affection, and humour in drunkenness that deflates high-blown romance. There

are many pairs of lovers, contrasting their attitudes and finding it difficult

to remain true to each other for the duration of the play. Some of the elements

of intrigue and farce, however, are difficult for the modern reader to enjoy –

often they seem merely means of obtaining plot complication and irrelevant

spectacular effects – and the suggestions of rape and sexual violence and

simply unacceptable to today’s audiences.

Circle Mirror Transformation – Annie Baker (3.7)

This fairly straight-forward play is set over the

space of a summer in a windowless dance studio with a wall of mirrors. The five

characters are taking adult creative drama classes complete with all the usual

warm-up exercises, focus games, and word associations. As they tell stories

about themselves and explain other people’s narratives they get to know each

other as the audience does.

Marty (55) is the teacher; James (60) is her

husband; Schultz (48 – separated from his wife) is interested in Theresa (35)

who does hula-hooping; Lauren (16) is obsessed by her mobile and hasn’t paid

for the class; she has ambitions to be a star and is disturbed by the seeming

irrelevance of the acting exercises.

When the characters are encouraged to air a secret in

front of the group without consequences, some big themes emerge. Each person

writes down their ‘confession’ and puts it into the hat, where someone else

withdraws it and reads it aloud. We learn these players are troubled by

addiction, abuse, love, fear and vanity. Their gestures are mirrored and

repeated back to them until they become transformed, and the exercise of

meeting yourself in ten years time is revealing. The play is not

earth-shattering, but it is entertaining.

The Death of King Arthur – Peter Ackroyd (3.8)

Peter Ackroyd presents a modern translation of Thomas

Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur in which

he promises to cut out the boring and repetitious bits while including all the

adventures and personalities. Much of the narrative is told with a deadpan

delivery, but there are a couple of lyrical passages between the spear

shattering and beheadings.

Having read many novels, treatises, and suppositions

about King Arthur (and having written my own university dissertation on the

continuing effect of the Arthurian legends on contemporary literature), I am

always struck by how little this source material is actually about Arthur,

himself. There is far more about Lancelot (and his perfidious relationship with

Guinevere) and the other chivalrous pair of lovers, Tristam and Isolde, whose

story accounts for over a quarter of the book.

A further quarter of the book is

taken up with the Quest for the Holy Grail, an adventure that does not include

Arthur, although it does ultimately destroy his kingdom. The knights ride

through the kingdom looking for adventures, a bit like the Famous Five but with

more beheadings. Although Arthur gets the title credit, Tristam and Lancelot

may be the exemplary knights of the tale.

This quest

emphasises purity at all costs, and purity seems to mean avoiding women who are

sorceresses, temptresses, treacherous and riddled with sin. Lancelot is given

no more than a tantalising glimpse of the Grail because he is impure and loves

Guinevere. Ackroyd remains coy as to what physicality their affection assumes.

“Lancelot and Guinevere were together again. Whether they engaged in any of the

sports of love, I cannot say. I do not like to mention such matters. I can

assure you of one thing. Love in those days was quite a different game.”

Already weakened by Quest for Holy Grail, Camelot is

destroyed by the factions for and against Lancelot and Guinevere. Arthur

grieves for his loss of friendship with Lancelot, whom he loves more than his

wife, a consideration that proves tricky for many of modern sensibilities. “It

is strange that I feel the loss of my knights more than the loss of my queen.

Queens can be replaced. But how can I find again such a noble company as that

of the Round Table?”

Despite his general lack of action and his reliance

upon others, Arthur is still a powerful symbol of a bygone era, largely due to

Malory’s testament. “King Arthur may simply be a figment of the national

imagination. Yet it is still a remarkable tribute to Malory’s inventive genius

that Arthur, and the Round Table, have found a secure and permanent place in

the affections of the English speaking people.”