The Palace of Holyrood House is the official residence in Scotland of Her Majesty the Queen. It has also been home to many famous royal residents including Mary Queen of Scots and Bonnie Prince Charlie.

The Palace of Holyrood House is the official residence in Scotland of Her Majesty the Queen. It has also been home to many famous royal residents including Mary Queen of Scots and Bonnie Prince Charlie.An audio-guide with a beautiful voice accompanies the tour, which explains the finer points of design as you go around the building. The forecourt and quadrangle are overlooked by the Salisbury Crags and it is here that every summer the Queen is symbolically presented with the keys to the city: it soon becomes apparent that there is a lot of symbolism built into these walls.

.jpg) |

| Detail on the fountain in the forecourt of Holyrood House |

|

| Queen Elizabeth II enjoys the Ceremony of the Key at Holyrood Palace |

|

| Incidentally, isn't it good that we haven't got so many martyrs in this country. All it would take is one nutter... Look how close she is to those bayonets! Not for our Queen the safety of a bullet-proof Mercedes rather than a walk-a-bout. |

The palace is built in the classical style with each floor representing a different architectural period – Doric, Ionic, and (on the top floor where the royal apartments are) Corinthian design – which gives balance, symmetry and a sense of proportion. Charles II rebuilt the palace with a team of architects based on the design of Versailles (the residence of his cousin, Louis XIV – many things were influenced by the French in this era, despite our outward hostilities towards them).

The palace is full of tapestries, portraits and processional rooms, each more elaborate than the other as you approach the king. It all begins with the Great Stair and ends with the King’s Bedchamber where the most privileged guests were met. The effect is meant to be increasingly daunting and I’m sure it was if you were approaching with a request that might terminate in your head being removed from your body.

The Dining Room features a Jubilee gift of silver – a dinner set of 3,000 pieces laid for 20 people (the table will seat between 30 and four people, removing or adding leaves as necessary). Presiding over all is a portrait of Bonnie Prince Charlie and, on the opposite wall, one of George IV, both wearing tartan.

Bonnie Prince Charlie had the support of the Scottish clans but was defeated by ‘Butcher’ Cumberland at the Battle of Culloden in 1745; thereafter the use of Gallic language and the wearing of tartan were strictly forbidden. So it was highly symbolic when George IV wore tartan in his portrait of 1820 proving the unification of England and Scotland and the acceptability of wearing tartan again.

The Throne Room is decorated with portraits of the Stewarts, red carpets, coats of arms and two thrones. This was the Guard Room in the time of Charles II where access to the monarchy was strictly controlled. Now it is where the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh hold their formal functions. Next in line is the Evening Drawing Room used by the Queen for state entertaining (this is where she met the Pope).

A portrait of the Queen Mother painted by Sir William Hutchinson has pride of place in this room. Everything else comes from the decorative pallet of Queen Victoria who first came to Scotland in 1837. She fell in love with Highlands but didn’t like the Palace so had tapestries and furnishings sent up from Windsor Castle.

The Morning Drawing Room, on the other hand, was decorated by the Comte d’Artois who hid out here after the French Revolution to escape his creditors. Being in the precinct of the abbey (with its own laws and dungeons; the oldest police force in the world, which is still on duty whenever the Queen is in residence) meant that debtors couldn’t be arrested. The new devolved Scottish executive was also appointed here, which may or may not be symbolic.

|

| The formal attire of the Royal Company of Archers |

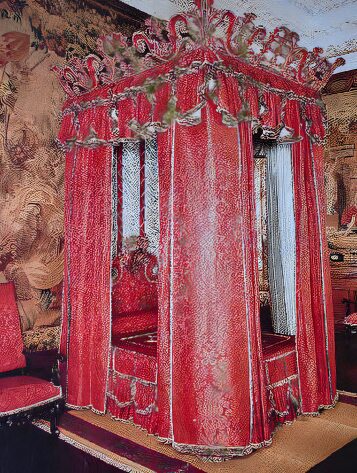

The King’s Bedchamber (with its plaster ceiling depicting images from classical mythology and four-poster bed) was only seen by the most privileged of visitors. The bed itself wasn’t used for sleeping but followed a French precedent to use it for state business – another peculiar (and indolent) French tradition. The next-door King’s closet was used as a private study and contains the most beautiful harp, piano, and green-embroidered chairs and curtains.

The Great Gallery is a long hall comprising one quarter of the building, now used for state occasions and investitures. Charles II commissioned a series of paintings of Scottish kings to assert the right of the Stewarts to rule Scotland. The portraits line the walls and they all look oddly alike, and they were hacked as revenge for Bonnie Prince Charlie trying to claim the British throne after his defeat at Falkirk in 1746. It’s always interesting to see the profound and unsettling affect that art can have.

In the Queen’s Lobby you can see the green velvet robe of the Order of the Thistle – the highest order of chivalry in Scotland (established in 1687 by James VII). Its English equivalent is The Most Noble Order of the Garter. The primary emblem is the thistle, being the national flower of Scotland, but they also get to wear all sorts of paraphernalia as part of their costume: a green mantle lined with white taffeta and tied with green and gold tassels; a black velvet hat plumed with white feathers; a gold collar depicting thistles and sprigs of rue; a gold enamelled St Andrew badge. The motto of this illustrious order is ‘Nemo me impune lacessit’ translated from the Latin as ‘No one provokes me with impunity’ which you can just imagine accompanied by the swish of a glove striking the face with bristling indignation.

The tour then moves to the Queen’s Antechamber in the tower where Mary Queen of Scots was imprisoned. The Queen’s Bedchamber (previously the private rooms of Lord Darnley) maintains the low light, heavy tapestries, imposing portraits and spiral staircases with stone walls that make the place seem even gloomier.

Mary had grown up in magnificent French renaissance palaces so this was a big change. Darnley (Mary’s second husband) was jealous of Rizzio (her advisor) and thought Rizzio would interfere with his chances of becoming king, so Darnley stabbed him 15 times in the outer chamber (which sounds quite painful).

Darnley himself was dead (killed by the Earl of Bothwell) less than a year later. Mary then married Bothwell which was so unpopular that she was forced to abdicate in favour of her son. She fled to England where she sought help from her cousin Elizabeth I but was imprisoned for 19 years and then tried and executed for treason aged 45.

The room contains various artefacts such as a portrait of Mary by Francois Chie in which you can see the pale complexion for which she was famed. The Darnley jewel which he had made for his mother has complex signs and symbols which are indecipherable to us but more obvious to people back then.

There is also in a display case the Holyrood ordinal – the rules for the conduct of the abbey. The abbey itself can be seen from the window, was named after a fragment of the cross, and was the inspiration for Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony.

.jpg)

The gardens are neat and impressive with a few wild corners where you can imagine the young princes straying after kicking their football into the flowerbeds. It’s a fascinating combination of history, tradition, ceremony and domesticity.

|

| This amazing image is by Mark Tisdale - check out more of his photography at www.marktisdalephotography.com |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)