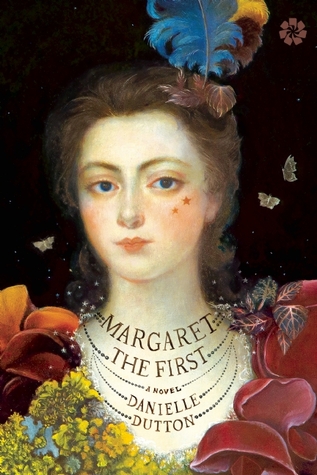

Margaret the First by Danielle Dutton

(Scribe)

Pp. 160

Margaret Cavendish was a poet,

philosopher and visionary. As a child she created imaginary worlds (populated

with thinking-rocks, humming-shoes, her favourite sister and Shakespeare, Ovid

and Caesar) and stitched little books together with yarn. “Eventually she

achieved fame, but it was not necessarily that which she sought, as children

chased after her carriage calling out to ‘Mad Madge’ and she became a

cautionary tale for young girls who dreamed of becoming too intelligent.

With the civil

war raging, she joined the court of Queen Henrietta Maria and followed her into

exile in France, where she met and married the much older William Cavendish,

Duke of Newcastle. William

was generally very supportive of her work and encouraged her to speak up and

express her thoughts. Through him, Margaret came into contact with many of Europe’s leading thinkers; but she was bashful and

awkward in society. When she was invited to speak at The Royal Society (the

first woman to be so invited, and the last for 200 years) she could only

stammer appreciation and rush away; causing Samuel Pepys to write, “A mad,

conceited, ridiculous woman. I do not like her at all.”

As a woman who published books of

her thoughts, she was considered doubly shocking. First that she had them,

which was scandalous enough, but to voice them was even more so. Furthermore,

she was childless, attempted cures for which included syringing herbs into her

womb and “a drench that would poison a horse.”

Many of her thoughts centred on the

physical world. As well as poetry and philosophy she wrote and published works

of extraordinary utopian science fiction and fantasy. In her book, Philosophical and Physical Opinions,

1655, against the prevailing ideas of the time, “I argued all matter can think:

a woman, a river, a bird. There is no creature or part of nature without innate

sense and reason, I wrote, for observe the way a crystal spreads, or how a

flower makes way for its seed.”

In contrast with much current

weighty (in size) historical fiction, this short novel (160 pages) covers

historical events in brief detail; The English Civil War is dealt with very

succinctly:

“The King of England was

convicted of treason. Then the King of England was dead. It was Tuesday. It was

1649. Parliament hacked off Charles I’s head outside the Banqueting House at Whitehall.”

Halfway through the novel, Danielle Dutton changes from first-person to third-person

narration. This ambitious move reflects the fame Margaret sought as people began

to talk about her after the coronation of Charles II, and the Cavendishes’

return to London.

While Danielle Dutton doesn’t

claim Margaret specifically as a proto-feminist, she does dwell on her issues

with equality, or the lack thereof. Indeed, the title comes from her own

self-honorific. “Though I cannot be Henry the Fifth, or Charles the Second, yet I endeavour to be Margaret the First”. She was far from

saintly, however, and, jealous of William’s success, she upstaged him at the

opening of his play by attending the theatre with her breasts bared and her

nipples painted.