I went to see this exhibition, Discovering Ancient Egypt at the National Museum of Australia with a friend. I mentioned that we 'learned' about the Egyptians in the same way that we 'did' the Greek and Romans, and he agreed. Later we both wondered whether that was, in fact, true, and whether we had gleaned information about this civilisation purely through osmosis and, in my case, trips with my mother to The British Museum.

The introductory info tells us that, "Egypt's legacy extends far beyond its modern borders. From the days of hunter-gatherer societies to the height of the pharaonic period, Egypt was a place of extraordinary artistic traditions and social complexity. At the heart of it all was a cherished belief in powerful gods and a society ruled by pharaohs who were also religious leaders. As Egypt traded and fought with neighbouring countries it became a society built on sophisticated ideas about government, religion, art and language."

"Its complex 3,000 year history encompassed over 30 dynasties of pharaohs, who ruled from different capital cities across Egypt. Researchers have divided the first 2,000 years into three periods: The Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom. The 'intermediate' periods were the intervening times when the country was ruled concurrently by more than one king. Nubians, Persians, Greeks, Romans and others gained power at different times in Egypt's history. The mutual influence of cultures and changes of rulership can be seen in the material culture that remains."

I think my fascination with global and ancient cultures is mainly based upon their mythology: their belief system of gods and goddesses; their creation stories and other explanations of various phenomena. I realise I am not alone in this, as many people line up to view artefacts, sculptures, writings and images of these bygone eras. There is great interest in the Egyptian's attitude to death, and the way they took objects with them to the grave to assist with their future in the afterlife. Maybe, it says a little too much about me that the very first picture I take is of a beer vessel.

"Beer was a popular beverage in ancient Egypt. It was nutritious and contained much less alcohol than beer today. Beer was consumed at religious festivals as well as being a staple in every household. Bottles and drinking cups like this one were placed in tombs to make sure that beer was available in the afterlife."

The ancient Egyptians believed in a world that was created and controlled by many gods, with the possibility of an eternal afterlife. Their complex belief system is understood through the architecture, objects and writings that have survived. This rich material culture also helps us to know more of their lived experiences and everyday lives.

It is a common misconception that the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with death. On the contrary, they loved life and saw death as the gateway to a new life among the gods. They prepared as well as they could for the afterlife, including planning extensive and expensive tombs - if they could afford them.

Although known somewhat unkindly as the bin chicken here in Australia, the ibis was considered a sacred bird in Ancient Egypt. Apparently large figures, like this sitting ibis, were often made of wood with details such as the head or feet cast individually in bronze and fixed in place. The bird, head and foot were once attached to a statue of the god Thoth, who was often represented as an ibis.

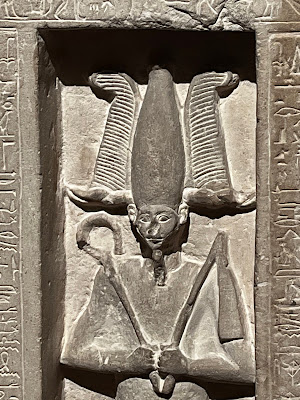

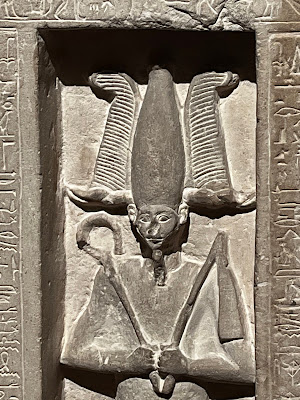

There is a cabinet which explains that the crowns worn by Egyptian rulers varied over time and reflected regional and symbolic conventions. The red crown was associated with lower Egypt, the white crown with Upper Egypt, and the double crown represented the unification of the two lands under a single ruler. The blue crown was often worn by pharoahs during war and was adopted as the main crown during the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom. Crowns were sometimes cast separately, such as the Isis and Osiris crowns shown here. The crown with cow horns flanking a sun disc is associated with goddesses such as Isis. This statue showns Isis wearing her crown and suckling her child, the god Horus. The Atef-crown, a variation of the white crown, represents Osiris and the feather of truth.

The first pyramids in Egypt were built during the Old Kingdom period (c.2543-2120 BCE) on the burial grounds of Memphis. They housed the tombs of royalty and are testament to the wealth and engineering knowledge of the Egyptians at the time. Wealthy officials built their own tomb as close as they could beside them. These so-called mastaba tombs had sloping walls like a pyramid but were lower, with flattened tops. The social status of their owner is demonstrated by the size and complexity of the tomb itself, and the stone statues, stelae (upright commemorative slabs), and luxury grave goods held within.

The false door is one of the three essential architectural elements of Old Kingdom mastaba tombs. The other two are the subterranean burial chamber, where the deceased were buried, and the chapel where the visitors could gather to honour the dead. Although the false door physically leads to nowhere, it was considered an important threshold that connected the realm of the living with that of the dead.

From the burial chamber, the dead person's ka or spirit would access this door to receive food and drink offered by the living. To guide the spirit, the deceased's name, title and image appears on the door, in this case Neferenkhufu, 'inspector of youths', and his wife, Isi, 'adorner of the king'. Perhaps they worked at the royal residence and were granted a burial close to King Khufu.

The Middle Kingdom (c.1980-1760 BCE) was a time of unity in Egypt. The Theban rulers of the time presented themselves as restorers of central authority and order. They re-established the capital near Memphis and began building pyramids again. But this was not just a restoration of the Old Kingdom. New forms of art, literature, religion and ideas flourished. Later generations of writers and scholars saw the Middle Kingdom as a golden age of Egyptian culture and its artistic styles held sway for centuries.

There was also a great collection of stelea - upright stone slabs or monuments, typically made of limestone or sandstone in Ancient Egypt, although harder stones like granite or diorite were also used, and sometimes wood in later periods. They contain information in the form of texts, images, or a combination of the two, and they serve multiple purposes, such as marking tombs, honouring deities and recording historical events.

Osiris, the god of the afterlife, was worshipped in the city of Abydos. His cult centre gained additional importance in the Middle Kingdom years. A man named Khu placed this stela at the processional road of the Abydos temple. The stela's inscription magically ensured the Khu and his family would receive a share of the temple's offerings.

|

| Offering stela of Khu and his family (c.1878-1843 BCE) |

This votive stela illustrates the priest Pamaaf making an offering to Re-Horakhty, the god of the rising sun, who has the head of the Horus falcon topped with the sun-disc of Re.

New types of funerary objects began to be produced during the Third Intermediate Period (c.1076-723 BCE), including figurines like these on long wooden bases. The figure here represents the combined underworld gods of Ptah, Sokar and Osiris. The crook and flail symbolise the gods' kingship over the afterlife. The base contains a rolled-up papyrus with an offering prayer for the tomb owner, a female called Tentamun.

|

| Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure |

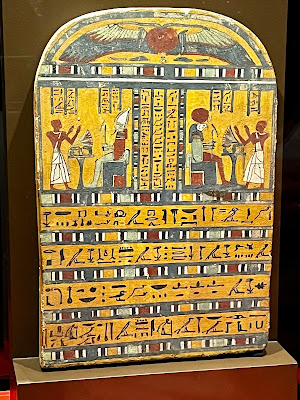

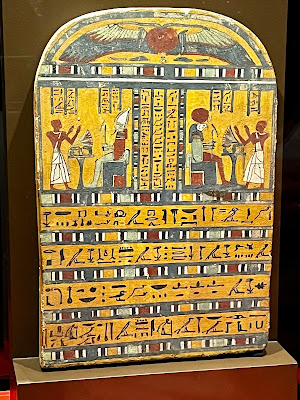

This funerary stela contains offering prayers on behalf of a man named Hor. On the left, he stands before the god Osiris. On the right, he faces Re-Horakhty, god of the rising sun. Although stelae can be made from a variety of materials, wooden stelae like this one are associated with the Late Period. As a funerary stelae placed in the tomb chamber its colours are well-preserved.

|

| Stela of Hor, Late Period (c.664-525 BCE) |

At the top of this stela a winged sun-disc represents the sun god Horus. Osiris, king of the afterlife and god of fertility, is seated on his throne with the four sons of Horus appearing from a lotus flower. They receive life from the sister goddesses Isis and Nephthys. Behind Osiris stand two figures: the larger is Imentet, the goddess of the West, and the other is Maat, whose judgement would allow the deceased into the realm of Osiris.

I find the parchment depictions and the Book of the Dead of particular interest. This scene shows Nesnakht's heart being weighed in the final judgement by the god Thoth before being permitted to enter the realm of Osiris in the afterlife. If a person's heart was found to be heavier than the feather of truth - the symbol of the goddess Maat - it was devoured by the demon Ammut and the soul would vanish into nothing. Not surprisingly, Ammut is depicted as a composite of the most dangerous of Egypt's animals: the lion, the hippopotamus and the crocodile.

|

| Book of the Dead of Nesnakht (Ptolemaic Perio, c.301-30 BCE) |

Only about one per cent of ancient Egyptians were fully literate. Learning to read and write was a privilege reserved for the social elite. High officials would portray themselves as scribes in their tombs to flaunt their literacy.

This is the first sheet cut from a long papyrus scroll that the priest Padikhonsu took into his tomb. Padikhonsu is depicted praising Isis and Osiris on the left and the god Re-Horakhty on the right. Together, these gods would guarantee Padikhonsu's rebirth in the afterlife.

|

| Book of the Dead of Padikhonsu, c.1076-944 BCE |

A branch of scholarship is dedicated to studying surviving Coptic Bibles from the period of early Christianity in Egypt. Greek letters and seven Demotic Egyptian characters were used to write Old Coptic, the ancient Egyptian language as it was spoken at the time.

There is no complete Old Testament in Sahidic, the most common Coptic dialect until the 7th snetury CE, but Gottingen University in Germany is coordinating a project to digitise text editions scattered throughout the world. This will provide a greater understanding of the Coptic language and early Christianity in Egypt.

The text states that this is a firsthand account of the two thieves that were crucified along with Jesus. This account differs from the biblical tradition in how it identifies which of the two thieves was on Jesus's right and on his left.

|

| Coptic Bible fragment (c.900-1100 CE) |

In 332 BCE, Egypt was invaded by Alexander the Great, the king of Macedonia. Some Egyptians, however, saw Alexander as having liberated them from Persian rule. After his death, one of Alexander's generals, Ptolemy, began a dynasty of Greek kings who reigned from the new port city of Alexandria. The last Ptolmaic ruler was the famous Queen Cleopatra VII. After her death in 30 BCE, Egypt became a Roman province. Both the Greek rulers and the Roman emperors adopted Egyptioan representations of power and had themselves depicted as pharaohs. While many new temples were built and dedicated to traditional gods, new religious movements emerged such as the popular cults of Isis and Mithras.

The goddess Isis was the sister-wife of Osiris and the mother of Horus. She was a significant figure in Egyptian mythology in the Graeco-Roman Period and was worshipped across the Roman Empire. This statue shows the blending of two artistic styles. The pose with her left foot forwrd is Egyptian, while the naturalistic style reflects Greek and Roman art.

|

| Statue of Isis (c.304-307 CE) |

Egytian gods played a vital role in maintaining the prosperity and order of the universe. They were thought to be responsible for important aspects of life, including the movement of the sun, the annual Nile flood, justice, childbirth, medicine, wellbeing and the afterlife. Offerings and rituals were performed daily to keep them pleased and solicit their blessings.

At temples built for and dedicated to specific gods, priests provided offerings of incense, food and drink and performed daily rituals. They shaved their heads to remain physically and ceremonially clean and used richly decorated equipment made from precious materials for their rituals.

Figures in statues wear feather crowns, cow horns and the sun-disc usually associated with the goddess Hathor. Along with Sekhmet and Bastet she had the status of Eye of Re, a vengeful female force that subdued the sun god's enemies. Each of these goddesses also had benign aspects. Hathor, for example, was also the goddess of pleasure, beauty, music and dance.

Thoth, the god of wisdom, writing, magic, art and judgement, was often depicted with an ibis head and pouring purifying water in rituals. The cat-headed goddess Bastet carries a sacred lion-headed collar, linking her with Sekhmet, often a more powerful form of the feline deity.

The hedgehog was perhaps admired by ancient Egyptians for its defensive qualities. When curled into a call, it resembled the sun-disc, which is reborn each morning.

The Egyptians often divided their gods into groups of three, called triads. Isis, Osiris and Horus form one such group. According to myths, Osiris was the original king of Egypt. His brother Seth murdered him out of jealousy and scattered his body parts all over Egypt.

Osiris's wife and sister, Isis, reassembled his body and revived him, but then the sacred Oxyrhynchus fish ate his phallus, forcing Isis to conceive their son and heir to the throne, Horus, with magic. Afterwards, Osiris could only rule over the afterlife, while their son Horus became king in the world of the living.

|

| Oxyrhynchus fish, c.1150-1170 BCE, made from soapstone |

The Upper Egyptian town of Per-Medjed was called Oxyrhynchus in Greek, which means 'town of the sharp-snouted fish'. This name refers to a species of fish that lived in the Nile and that, according to mythology, ate the phallus of Osiris after he was dismembered by his brother Seth.

Statues provided a conduit for communication between the living and the dead. This statue, depicting a man with his female relatives on either side, may have stood in a tomb chapel. Like other statues of its kind, the sandstone surface was originally painted. Traces of this colour can still be seen today.

This statue is of Irnakhtamun and his wife, Wawi, shown with her hand on her husband's shoulder. The long, pleated garments and heavy braided wigs are typical of the style of the New Kingdom. This statue probably stood in the couple's tomb or a tomb chapel to receive offerings.

When the Egyptians buried their dead, they put many things into the tomb with them. The theory was that they would need these things in the afterlife (hence the beer and wine), and statues. The afterlife was a place of peace and order. But, as in life, people were at the whim of the gods and other powerful forces. Magic spells and rituals were required to assist a person's passge to the afterlife, along with food, drink and other necessities to sustain them.

This wooden model could have ensured the owner an eternal supply in the afterlife of beer and bread - the staples of the ancient Egyptian diet. It shows significant moments in the baking of bread, with a foreman standing by the door to oversee the workers, including three men hoisting sacks of grain. Behind them, a baker reaches out to an open fire piled with bread moulds. Nearby, another man stands with a large vessel for brewing beer.

|

| Model granary |

The Egyptians believed that through their magic their body would be revived and they would find themselves in a realm with gods and other supernatural beings. Here they would be judged by various gods and, if successful, transfigure into a being with powers to travel to places in the afterlife. The Field of Reeds was one such destination, with land suitable for farming and marshes filled with wildlife for hunting. It was also where a person would be reunited with their dead parents.

Collars, necklaces and other items of jewellery were worn daily by Egypt's richest people. These pieces served as both protective amulets and aesthetic embellishments and were made using glass, ceramic, faience [a glazed non-clay ceramic - often blue or green], precious stones and gold.

Considered divine by the Egyptians, gold was especially prized. They believed it represented the flesh of the gods and was pure and powerful. Ancient Egypt was renowned for its access to gold-mining regions stretching across the desert east of the Theban region and south to the present Sudan border. Its artisans were also celebrated for their gold-working traditions.

Shabti or ushabti were funerary figurines placed in tombs among the grave goods, and were intended to act as servants or minions for the deceased, should they have to do any manual labour in the afterlife. The word shabti means 'the one who responds'. They were geneally distinguished from other statuettes by being inscribed with the name of the deceased. In some tombs the floor was scattered with ushabti figurines, whereas in others the ushabtis were packed neatly into a box.

This shabti represents the man Ipy in mummified form with a separate coffin. Both pieces are inscribed with hieroglyphs, with reference to the sky goddess Nut, mother of Osiris, on the coffin.

Ancient Egyptians believed a deity could take the form of a particular animal in the world of the living. Thoth, the god of wisdom and writing, for example, could appear as a baboon or an ibis. Millions of mummified ibises - offerings to Thoth - have been found in catacombs at Hermopolis, Abdyos and Saqqara. Ancient Egyptians offered mummified ibises to Thoth in exchange for a blessing.

Mummification of animals was a common practice in the Late and Greco-Roman periods. Mostly, ancient Egyptians mummified animals so they could be offered to a deity in a sanctuary. Through mummification, the animal would reach the deity in the afterlife and could ask for the favour of its donor.

The mummification of animals was a major industry, with cats, ibises, snakes, fish and crocofiles in particular reared solely for this purpose. But X-rays have revealed that many mummified animals and their coffins contain only feathers or a few bones. Through magic, a part could represent the whole animal.

Mummified cats were offered to the goddess Bastet, who is commonly depicted as a cat or with a cat's head. Additional features were sometimes modelled onto the linen - in this case trinagular-shaped ears. X-rays show that the animal has a broken neck, indicating it was killed specifically to be mummified.

Mummification required skill and precision. A flint-stone knife was used to create a single incision in the left side of the body from where the organs could be extracted. The brain was removed thorugh the nostrils using a hook. A salt, called natron, was then applied to dehydrate and preserve the body. Finally the body was wrapped in precious linen bandages. Often these strips were soaked in a resinous mixture, which acted like glue.

Canopic jars were used to store and preserve the lungs, liver, stomach and intestines of a mummified person. Each organ was protected by one of the four sons of Horus, with the aid of a specific goddess. The son Imset and the goddess Isis were responsible for the liver; Qebehsenuef and Serqet, the intestines; Duamutef and Neith, the stomach; and Hapi and Nephthys, the lungs.

Early canopic jars were plain. Later, during the Middle Kingdom, the lids were decorated with the figure of a human head. Later still, the lids would depict the heads of the sons of Horus.

This jar from the New Kingdom has a lid representing Imset, protector of the liver. He is invoked in the now much-weathered inscription. Only traces of resin, a plant substance used during the mummification process, remian in this jar.

Canopic jar of Wahibre - this jar's lid is in the shape of a falcon's head and represents Qebehseneuf. He was in charge of guarding the intestine.

A person's heart was rarely removed from their body during mummification because it was needed to judge their character before they were permitted to enter the afterlife. Heart scarabs and the spells written on them prevented the heart of the deceased from revealing any sins during the ceremonial wreighing of the heart by Thoth.

Saqqara was an important burial ground for the city of Memphis. Although Egyptian kings were buried elsewhere after the Old Kingdom, Saqqara remained a vital religious and funerary area. A mix of non-royal tombs and temples and shrines were built there throughout pharaonic history. The first monumental building made of stone rather than mud brick - the step pyramid complex of King Djoser - was built here around 2600 BCE under the direction of the famous official Imhotep. Through their excavations in Saqqara, the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities has gained insights about the history and original context of its collections, shedding new light on the tombs where statues and reliefs once stood, as well as rediscovering previously lost tombs.

The selection of tomb statues are fascinating. This one is the tomb statue of Amenhotep-Huy, in limestone. Amenhotep-Huy was the king's chief stonemason. He is depicted seated on a pillow with his knees drawn up and his arms crossed. This style of pose allowed more room for images and inscriptions to be applied. The relief on the front of this statue shows a representation of two of Amenhotep-Huy's sons, Naherhu and Amunwashu.

The relief on this pyramidion shows the royal scribe Pauty raising his hands in adoration of two sun gods. On the side that would have been facing east, he worships the rising sun represented by the falcon god Re-Horakhty, whose name refers to the sky between the two horizons. On the western side,Pauty venerates the setting sun represented by the god Atum.

|

| Pyramidion of Pauty (New Kingdom c.1539-1077 BCE) |

The exhibition concludes with a number of artworks indicating the myriad persepctives of ancient Egypt. Europeans began to explore Egypt in the 16th century. But long before that, Islamic conquests from the 6th century CE onwards brought with them Arab scholars who contributed much to the study of ancient Egypt. They valued Egypt as a land of science and wisdom and were particularly interested in the Egyptians' understanding of alchemy and medicine. These scholars, whose names are often obscured from the historial record, were keen to protect the pyramids and other monuments of ancient Egypt.

David de Leu de Wilhem was one of the first Dutch people to visit Egypt, establishing a trading business in Aleppo, Syria. In 1620-21 he acquired a mummified person and many Egyptian antiquities, which he donated to Leifen University, Later, in 1698, Cornelis de Bruyn, an artist from The Hague, published a richly illustrated account of his travels in the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Levant, including Egypt, fuelling the West's fascination with the ancient past.

When de Bruyn made this drawing in 1681 the body of the Great Sphinx was still covered in sand. De Bruyn descibed the interior and exterior of the pyramids, which he rightly understood to be the tombs of Egyptian kings.

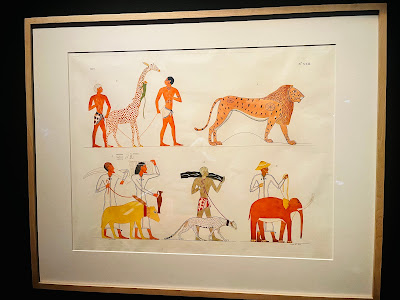

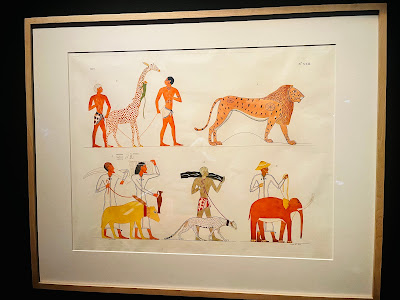

Jean-Françoise Champollion (1790-1832) was a French philologist and orientalist, known primarily as the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphs (The Rosetta Stone is a greatest hit) and a founding figure in the field of Egyptology. Once he was able to translate hieroglyphs, he organised an expedition to Egpyt with his student Ippolito Rosellini to study and record inscriptions and reliefs on ancient monuments. By 1834 Rodellini had published his work in three large books of images and nine textbooks known as I monumenti dell'Egitto e della Nubi (The Monuments of Egypt and Nubia).

Rosellini's books, along with those produced by Napoleon's scholars, are regarded as part of the foundational texts for the newly established Western academic study of Egypt. The drawings contained within remain useful today as they document, for example, colours and patterns on monuments, walls and ceilings, which have since faded or disappeared entirely.

This plate shows a relief from the Abu Simbel temple in Nubia. Rameses II, armed with a mace, is striking prisoners of war in the presence of the god Amun-Re.

|

| Victory scene with Rameses II by Ippolito Rosellini |

|

| Tomb chamber motifs by Ippolito Rosellini |

|

| Various species of quadruped animals by Ippolito Rosellini (they represent animals brought to Egypt as gifts) |

|

| Giraffe! |

And then we come to the gift shop. I do love fossicking through the wares in a museum gift shop, where there are some quality pieces and a whole heap of tat. You be the judge...