Modewarre by Patricia Sykes

Spinifex

Pp. 90

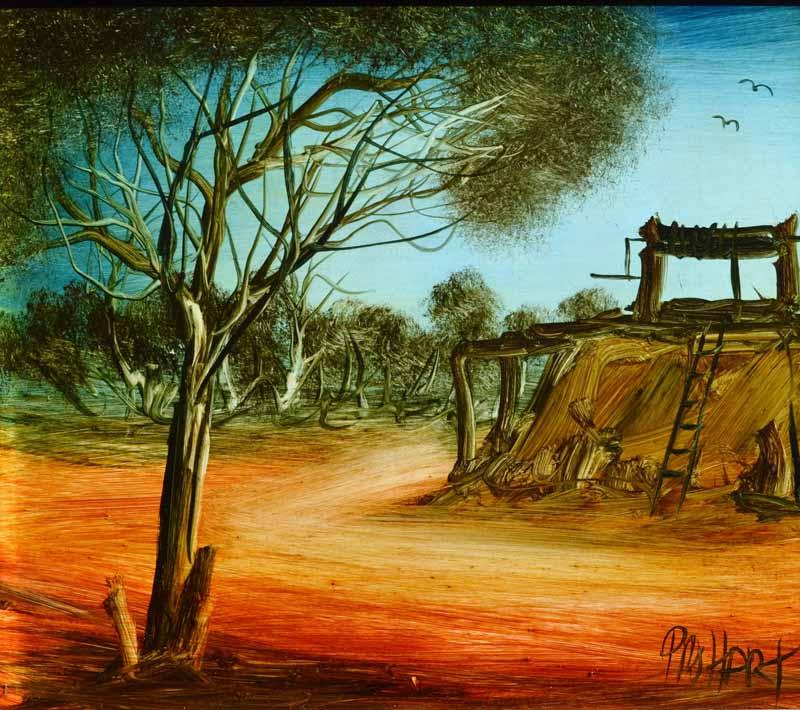

Modewarre is the indigenous word

for musk duck, a creature at home on land, water and air. Through her poetry, Patricia

Sykes explores various histories and the boundaries between them which blur and

blend. She splits the poems into three sections: House of the Bird, House of

Water, and House of Detention, examining words and their connotations, dwelling

on reflections, refractions and altered perceptions.

Naming things robs them of their

magic and power, as we use “language, so impossibly cumbersome/ for discovering

the true weight of things/ the grandmother would have known”. The literary

fragments are almost Sapphic with physical and sensual meaning: “as always the

modewarre/ places faith in its eggs/ yolk and the sun/ breed each other”. The

strong bonds of belonging and connection to land go beyond words, until the

frustration is clear in a poem such as eponymous,

“to the interrogator who keeps asking/ ‘so are you still suckling on myths of

place?’/ I say try the enigma address/ the bird who keeps vanishing in water –”

The

poems recall the land and the life before the colonists came, and also the

sheer incomprehension of the invaders dealing with the loss. In eupathy (right feeling of the soul) she

sees the land from above as though flying with the eagle. “to talk now/ of

whether this is still so/ or if the eagles in free flight/ are an option/ to

speak of/ options, land, again/ once more/ not as that which was taken/ is

un-ownable/ contracting and crowded/ but as lava shift/ the heat of a river/

always underfoot/ in a molten indifference/ to politics”. There are layers of

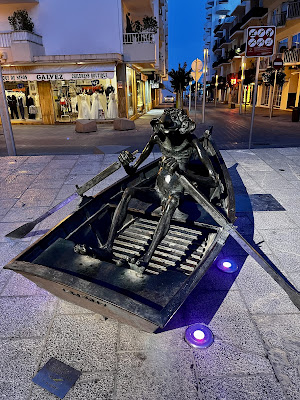

knowledge contained in a word, such as the poem, ‘brid’, eight darkness in which

‘brid’ is the name given by Nyangangu, a Yolgnu artist of Northeast Arnhem

Land, to her bird carving. “there, where you are,/ bred of earth, breeding sky/

working the uplift, wingbeat/ as if sculpting a refusal/ to die of white

history”.

The world is a palimpsest and so

is the brain – our thoughts and memories are malleable. Birds connect people

and places, and are often totems for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

people, helping to define kinship with people, their Country and nature,

connecting to the roles and responsibilities of a mob, offering protection and

foreshadowing danger and momentous events. This connection extends throughout

the world as the birds migrate along their own songlines.

Means of expression are

insufficient, with even mechanics of speech and typing unable to capture the

richness of the language. “this keyboard’s/ tireless tap-tap mouth/ which

cannot voice/ the interior ‘n’ in Nyangangu/ the one with the tail/ the sound

of ‘ng’ in singer”. And yet the words can be damaging and belittling. “how the

eyes like linguists are never satisfied/ how they’ll poke and pry into any

lexicon”, wanting to preserve and capture, destroying the natural.

The poems in House of Water are

concerned with childhood, disease, death, invasion, cattle, birds, and bunyips.

Roads are built over traditional lands, only to crumble and fray at the edges

demonstrating their impermanence in the liminal space. “what never was field/

become paddock become/ fences become livestock/ the cattle the sheep/ foraging

for the hoofprints/ they lost the last time/ they departed a shore”.

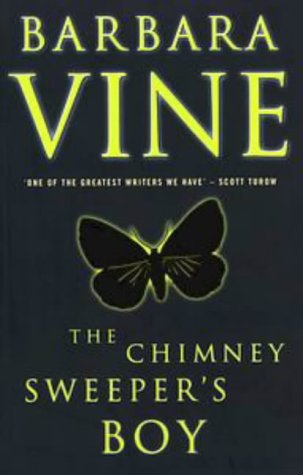

In the House of Detention, the

poems move on to highlight migrants trapped in refugee camps, prisoners in

cells, wives in marriages, women in motherhood, caterpillars who will one day

be butterflies, political constraints, and people wanting to be “at home in

every world/ where exile does not exist”. In great-aunt narrative among the excised lands, Sykes leans upon the

double meaning of refuse (verb and noun) as it relates to denial and pollution:

“oh my Canberra…/ high city of

presumptive cleanliness/ among the dirty waters exuding from the workplaces/

the smell of your refusal laws”. She uses a rare capital letter in this poem,

which must surely be ironic as her punctuation is clean and almost entirely

absent.

Modewarre is a great

collection of powerful fragments, connecting words to the echoes of previous

language both spoken and unspoken. It is a reminder that we are merely one of

millions of moving parts that comprise our environment, expressing a concern

for what will happen to the delicate balance once we form a pyramid and place

ourselves at the apex.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-626974567-defc9220866c4e679c8d244dfbb997bb.jpg)