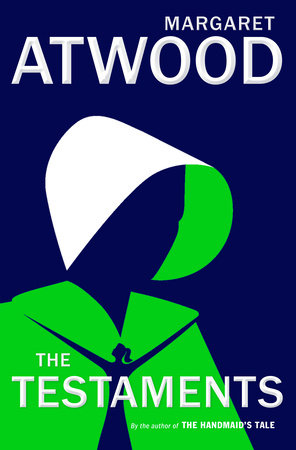

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood

Chatto & Windus

Pp. 415

In her acknowledgements, at the end of The Testaments, Margaret

Atwood thanks “the readers of The Handmaid’s

Tale; their interest and curiosity has been inspiring.” If my desire to

know what happened after The Handmaid’s

Tale is in any part responsible for the writing of this book, 35 years after

its predecessor, you’re welcome. It’s been a long time coming, but it is

certainly worth it, and after all this time, it still has a clear directive: “We

must continue to remind ourselves of the wrong turnings taken in the past so we

do not repeat them.”

Much of the novel is a thinly-veiled polemic against

totalitarianism. One of the narrators is Aunt Lydia, who warns against assuming

all that is new is good, and ignoring past wisdom, especially that derived from

women. “The corrupt and blood-smeared fingerprints of the past must be wiped

away to create a clean space for the morally pure generation that is surely

about to arrive. Such is the theory.” She keeps a secret diary, which is part

confession, within the hollowed-out pages of a book, incorporating sarcasm about women’s perceived roles with asides

about the veracity of history and the stories we are conditioned to believe.

Her wit and humour are displayed throughout her manuscript,

and she

rambles with her folksy sayings and pragmatic methods. There is a dark side to

the humour, however. Some of the young girls threaten to will kill themselves

if they are forced into marriage, afraid of male sexuality. “No one wants to

die. But some people don’t want to live in any of the ways that are allowed.” It

is horrifically symptomatic of totalitarian regimes: women and children suffer

as men rape and take what they want.

Before Gilead,

Lydia was a judge, and the new (male) rulers did not want her around. “Any

forced change of leadership is always followed by a move to crush the

opposition. The opposition is led by the educated, so the educated are the

first to be eliminated.” Persecution was fairly indiscriminate: “All that was

necessary was a law degree and a uterus: a lethal combination.” Now she is a

cornerstone of the Gilead government, but she knows power can be overthrown and

statues easily toppled.

Whereas The Handmaid’s Tale was focused primarily

on June and the other handmaids and was claustrophobic in tone; this novel is

narrated through three different voices: Aunt Lydia, Agnes, and Daisy. As the

title suggests, they are putting their name to a document they have sworn to be

true, and the novel opens up into a wider world. Where there are women; there

is communication. “The Aunts, the Marthas, the Wives: despite the fact that

they were frequently envious and resentful, and might even hate one another,

news flowed among them as if along invisible spiderweb threads.”

Treatment of women by men, who seek to dominate and oppress

them, is an over-arching motif. Women must be pure: those who enjoy sex

and physical relationships are sluts. Women should be nurturers and carers. Women

are blamed for their indiscretions; men are not held accountable for their deeds:

men must act on their urges; women must not encourage them. Women exist to

reproduce; their bodies are baby-making factories and do not belong to them

individually. “Every woman wanted a baby, said Aunt Estée. Every woman who wasn’t

an Aunt or a Martha. Because if you weren’t an Aunt or a Martha, said Aunt

Vidala, what earthly use were you if you didn’t have a baby?” It’s all

depressingly familiar.

Aunt Lydia keeps

secrets so she can blackmail people later when it is useful to do so. “All that

festers is not gold, but it can be made profitable in non-monetary ways:

knowledge is power, especially discreditable knowledge. I am not the first

person to have recognised this, or to have capitalized on it when possible:

every intelligence agency in the world has always known it.” Fake news and

students on strike are recognisable tropes. The combination of adulterated

Shakespeare and pertinence to contemporary affairs is deliberately unsettling. Atwood

uses the language of fairy tales, but the chilling ones like Sleeping Beauty and later comparisons

with Bluebeard.