Set in 1825 in South-West Ireland,

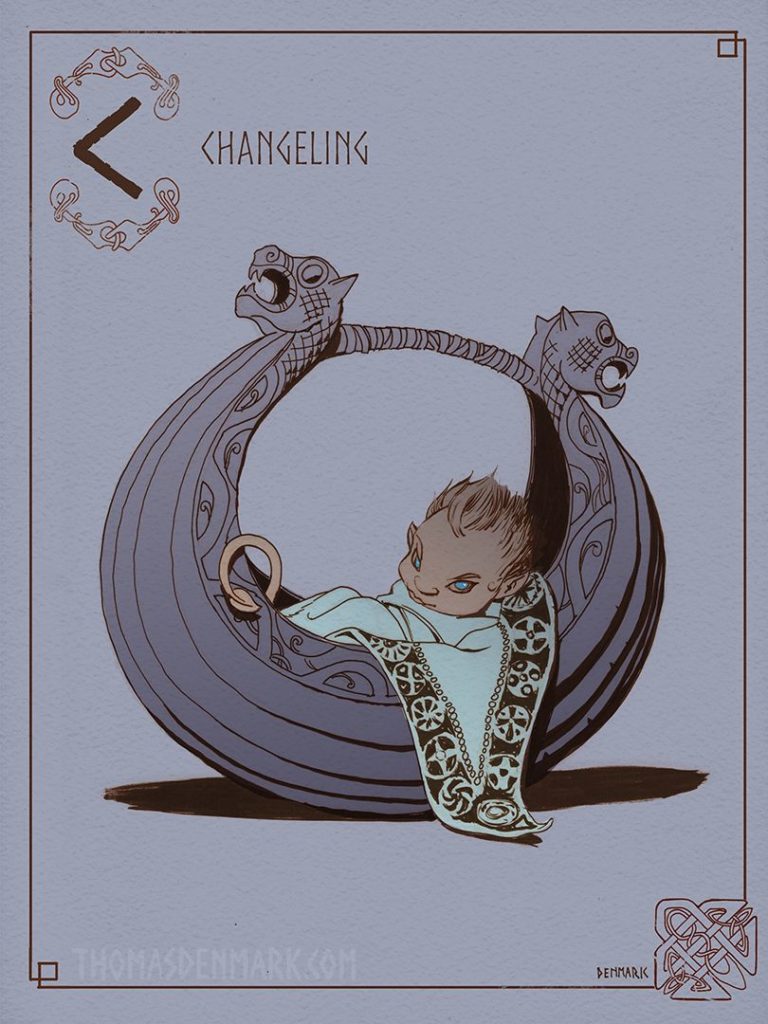

this novel explores liminal spaces and inexplicable things. In this world many

follow the ‘old’ beliefs that children (and adults) could be stolen (swept) by

the fairies to be replaced by changelings. Folklore and superstition are

important here; herbs and flowers have healing and harmful powers; each chapter

is named for one and begins with a botanical pen and ink drawing.

Nóra is caring for her daughter’s

child, Micheál, after her own daughter has died. The boy has a disability which

prevents him from speaking or walking and, after her husband Martin’s

mysterious death at a crossroads (a place of magic), rumours abound that

something may be not quite right with child. Nóra hires a servant girl, Mary,

to help her to care for Micheál, and when Mary hears gossip from the women at

the well that Micheál may be a changeling, she and Nóra enlist the help of Nance,

the wise woman in the woods, who is believed to consort with the fairy folk, or

the Good People, as they are also known.

This is a traditional battle

between female and male energy, where women with knowledge are punished as

witches, while men and priests hold all the power. There are glimpses of

domestic violence and mental and physical cruelty in the community as the women

cower to their husbands. Nóra is isolated in this society and, when there is

cold and hunger, she is the last to be considered, leaving her to make wild

choices.

We first meet Nance when she

turns up at Martin’s wake and begins keening. The new priest, Father Healy,

takes an instant dislike to Nance and lectures, against “the old ways that keep

Irishmen at the bottom of the pile. ’Tis a new age for Ireland and for the

Catholic Church. We’re to be paying our pennies to the Catholic campaign, not

to unholy keeners.” Depending on who’s telling the story, Nance is either the “handy

woman” or the “interfering biddy” who believes in the potency of the old ways

and receives several visitors “mainly the men... who did not trust the doctor

or could not afford his labelled tinctures” to whom she supplies herbal remedies.

Brimming with Hardy-esque pathetic

fallacy, the novel credits the seasons with paramount importance in an

agricultural community. Life is cyclical in its natural rhythms: Nóra and Nance

both believe that all is connected in ways the Catholic Church doesn’t

encompass. Under the instruction of Nance and with the reluctant assistance of

Mary, Nóra tries to return the changeling child to the fairy world by

submerging it in the river.

The novel is based on a true

story of infanticide in 1826 where an old woman of advanced years known as

Anne/Nance Roche was indicted for the wilful murder of Michael Kelliher/Leahy,

who had been drowned in the river Flesk. In this version, the final chapters take

place in a courtroom, which opens a completely new world, and exacerbates the claustrophobic

nature of the valley community. The characters are trapped in crucible of

superstition, poverty and geography, with no way out except for torturous

ordeals of fire and water.