- Come Death and High Water by Ann Cleeves (MacMillan) - This is the second in the George and Molly Palmer-Jones series in which Ann Cleeves acknowledges the influence of the Golden Age mysteries. A group of birdwatchers gather for a committee weekend on an island which is cut off by a storm and a high tide. The first victim is the cartoon-like character (which the author revels in creating) Charlie Todd, who will obviously be bumped off as he has decided to sell off the island and everyone has a motive for murder. Each suspect is interviewed separately by the curt and proessional Superintendent who has been sent over to conduct the investigation, while our man George observes and passes comment on the proceedings. He is dedicated to the task, but also swept away by the brleak and beautiful scenery. “Nothing mattered but the effort of walking against the wind, the sand stinging at his eyes and the surface water blowing around his boots.”

- Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (Penguin) - This novel is so similar to Bernadine Evaristo's Girl, Woman,Other that I'm surprised there wasn't a plaigirism case. This was written first and is American, whereas Evaristo's focusses on the British immigrant experice. The book has a family tree in the beginning, which is essential, as it covers the lives of several different characters, each one in a separate episodic chapter, but all related. The stories of the multiple generations descending from Ghana have distinct female voices and a shared focus on the historical and social complexities of the Black female experience.

- Small Gods by Terry Pratchett (Corgi) - In the thirteenth novel of the Discworld series, Terry Pratchett takes pot shots at organised religion, squabbling philosophers and the nature of belief. These are such easy targets that this novel feels lesser than many of his works, like shooting fish in a barrel. The story opens in the city of Omnia, whose chief god, Om, has been reduced to a pitiful existence in the form of a turtle because no one really believes in him anymore. Gods need belief to live and thrive, and they fear becoming small gods, barely existing out in the desert wastelands with no believers at all. Mere mortals struggle to make sense of life – hence the plethora of philosophers – but the gods are literally above it all, playing games with humans as their playthings. The novel was written in 1992, but its discourse on certainty in religion and politics feels particularly pertinent in our post-truth world thirty years on.

- The Dead of Winter by Nicola Upson (Faber & Faber) - This is the ninth in a series featuring the writer Josephine Tey as a detective. It's a smart concept (I believe it's also been done with Agatha Christie in a similar role) and although I haven't read any of the others, this was enjoyable enough out of sequence. The novel is set in 1939 where Nazis and swastikas abound, and Hilaria St Aubyn is raising money for refugees by hosting a Christmas party at a castle on St Michael’s Mount, which people bid to attend. The mystery guest, accompanied by Tey’s old pal Detective Chief Inspector Penrose, is none other than the world’s most famous movie star, Marlene Deitrich. It’s all a bit bonkers and quite fun as the incongruity of the joy of seasonal festivities mixes with the horror of murder. It’s full of thrilling set pieces, such as being at the mercy of the tides and the weather with all communication lines cut off. There are also some genuine plot twists which keep it intriguing.

- The Choke by Sofie Laguna (Allen & Unwin) - This is relentlessly grim; Australian poverty porn with a rape thrown in – in the style of Trent Dalton. Everyone is suffering some form of trauma and neglect, and most of the physical violence is perpetrated against women. Justine lives with her grandfather, pop, as her mother, Donna, died giving birth to her, and her father, Ray, comes and goes at random. She has two half-brothers, who fare no better in the paternal stakes, and their mother, Relle, will not even look at Justine as Ray left her for Donna. Pop is a Korean vet, struggling with PTSD, and Justine’s only friend is Michael, a boy who is taunted at school due to his cerebral palsy. Told through Justine's eyes, this simply doesn't ring true - she is capable and dyslexic, in a world of firing guns, collecting eggs and smoking cigarettes but has no idea about pregnancy. You know where this is going.

Friday, 10 May 2024

Friday Five: Books Read in April

Wednesday, 26 January 2022

Colouring in between the lines: Stanley and Elsie

Never read about your heroes. Sir

Stanley Spencer may have been a brilliant and talented painter who created

works of magnificence, but it seems he was a very selfish and unpleasant

individual. His life, like his artwork, was unconventional and would have been

described at the time as Bohemian. At the time of the novel he is married to

Hilda (Carline) and they have two children, but he has an affair with a woman with whom

he thinks he shares a background, Patricia Preece. Patricia is in a relationship

with Dorothy Hepworth, which continues throughout her affair with Spencer. He divorces

Hilda and marries Patricia, who continues to live with Dorothy, and Stanley

returns to Hilda whom he cares for through cancer until her death. These are

facts and, therefore, not spoilers.

|

| Dorothy Hepworth, Patricia Preece, Stanley Spencer and Jas Wood at the wedding of Preece and Spencer (1937) |

The novel is narrated by Elsie,

who was the housekeeper and, at times, confidant to both Stanley and Hilda, and

she learns about and talks to the man in a manner that suggests her position is

obscure. She wonders how deeply to involve herself in the lives of these

people, about whom her parents have warned her, because artists are all a bit

odd. She claims to not want to cause difficulties, and yet she is keen to be a

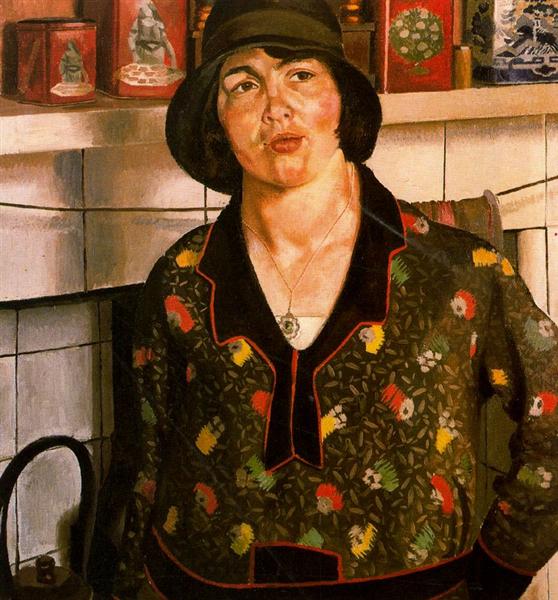

part of the relationship. When Stanley paints her and calls the painting Country Girl, she is offended that he

sees her as a simple village girl, but he counters the painting is of “the girl

I’ve watched so closely, the girl whose neck I love, whose mouth, whose legs,

whose whole demeanour – not because I love them,

but because I love her. I called the

painting Country Girl because it

celebrates everything you and I have in common.” This is definitely not fact

but overt fiction. Supposedly the novel is more about Elsie than his wives,

Hilda and Patricia, but although Elsie narrates, we don’t learn much about her.

Maybe she just isn’t a very interesting character.

|

| Country Girl by Stanley Spencer (1929) |

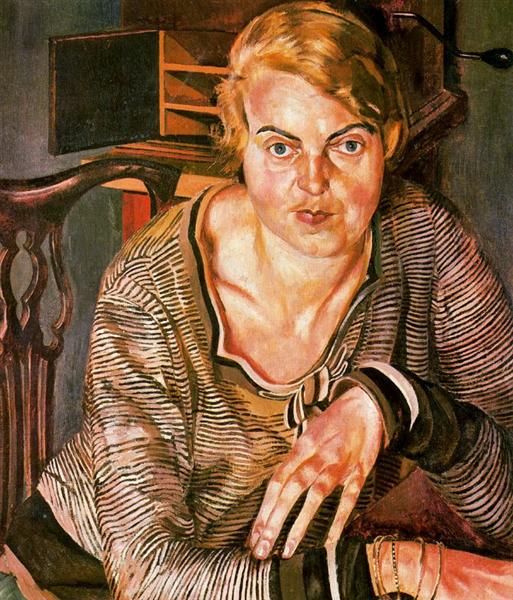

Stanley makes all the women in

his life desperately unhappy, but Patricia seems to want him for his networks

and his introductions to galleries. She is very glamorous, but not as good a

painter as Dorothy, whose works she passes off as her own (with Dorothy’s

consent). After the breakdown of Stanley and Hilda’s marriage, Patricia wonders

whether to marry him or not, knowing she will be damned either way. “I’d rather

be a money-grabbing bitch than a penniless whore.” Dorothy warns her, “People

will take Stanley’s side. He has a talent for rousing sympathy, and the man is

never at fault when there’s a woman to blame.”

|

| Portrait of Patricia Preece (1933) by Stanley Spencer |

Hilda loves the garden and

growing things; it is holistic and she is skilled at it, although Spencer

dismisses it. On one occasion she brings in some snowdrops from the garden and

when Patricia visits with some exotic blooms she has bought, he dumps the

snowdrops out of the vase to replace them with the showy blooms, in an

obviously symbolic gesture. Metaphors are stretched a bit thin to cover Stanley’s

attitude to relationships and other people, as Hilda tells him, “Life’s one big

picture as far as you’re concerned. You put yourself at the centre of it and

paint the rest of us around you, hoping we’ll stay where you want us to. But

real people are different. Real people live and breathe and change, and not

only at the stroke of a brush.”

|

| Hilda with Bluebells (1955) by Stanley Spencer |

Spencer was skilled at organising multi-figure compositions such as in his large paintings for the Sandham Memorial Chapel, dedicated to the fallen of the First World War. He himself suffered from PTSD after the war, and tried to highlight and celebrate the mundanity of the army, including figures of men washing uniforms, cleaning tackle, studying maps, eating breakfast or making tea in his images. Spencer also has a complicated relationship with religion and, besides painting the artwork for the chapel, he paints Jesus into many of his pictures, often doing simple tasks as one of a group, not as the principle figure in the image, but as one of the crowd. He keeps a copy of St Augustine’s Confessions by his side while at work as inspiration. “There’s a passage about serving God through ordinary things. ‘Ever busy, yet ever at rest. Gathering yet never needing, bearing, filling, guarding, creating, nourishing, perfecting, seeking though thou hast no lack.’ As soon as I read that, I knew why I was there. It was all a service to God, even if I wasn’t fighting.”

|

| Paintings at Sandham Memorial Chapel |

Through his art, Spencer is intrinsically linked to Cookham, the village on the River Thames where he was born and spent many years of his life. He referred to Cookham as ‘a village in heaven’ and in his biblical scenes, fellow-villagers are shown as their Gospel counterparts, expressing both his unconventional faith and the compassion that he felt for his fellow residents. I know the area well, and I can picture the streets Nicola Upson writes about in the novel, and the train journey into London, which Elsie takes when visiting Patricia in the city.

|

| Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta: Dinner on the Hotel Lawn (1957) by Stanley Spencer |