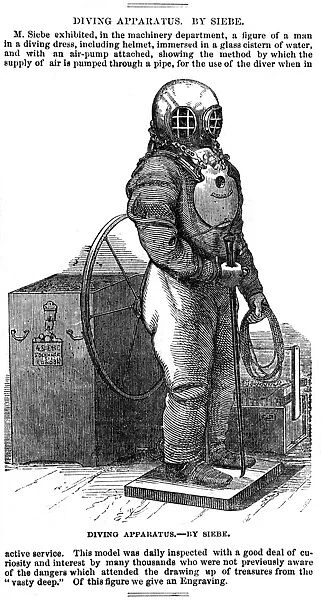

Continuing my visit to the Museum of Tropical Queensland, I enjoyed a side room, which contained a truly fascinating exhibit about diving apparatus and how it has changed through the years.

|

| Part of the Langley Diving Helmet Collection |

In the late 1830s, Augustus Siebe invented the first closed type of diving dress: a helmet sealed to a watertight suit. With the closed dress, divers could bend over and had more security. Siebe also built efficient hand pumps to force compressed air down the hose to the diver. Standard dress revolutionised diving, making the underwater worker an essential part of both salvage and civil engineering. Without standard dress divers, many of the great building projects of the Victorian era - bridges, lighthouses and tunnels which we still use today - could not have been built.

|

| Augustus Siebe, diving helmet c.1840 |

This is the second oldest 'closed' standard-dress diving helmet known to exist. The standard diving helmet is a tinned copper dome (or bonnet) attached to a canvas and rubber suit by way of a corselet. The suit is placed over the bolts on the corselet and clamped down with metal straps called brails tightened with nuts to form a seal. Air is pumped into the helmet through the inlet valve to give the diver fresh air to breathe, and it escapes through the outlet valve. There is usually a front and two side windows (or lights), and an additional top light is sometimes fitted to give an upward view.

The inlet valve is at the back of the bonnet and is at a right angle, turning down. This is to prevent snagging, the air hose comes down in front of the helmet, under the arm and back up to the back of the bonnet. Inlet valves are one way valves (known as non-return valves). This is so that if the air hose is cut or seriously damaged, the compressed air within the helmet is prevented from rushing out and creating a vacuum squeezing the diver's head up the air hose.

The outlet valve, usually positioned around the diver's right ear, is adjustable so that the flow of air escaping from the helmet can be controlled and the diver can adjust their bouyancy. Screwing the outlet valve closed ensures that less air escapes and the diving dress fills with air. The diver becomes positively bouyant and floats to the surface. Unscrewing the outlet valve allows air to escape, deflating the diving dress and the diver sinks. The outlet valve can be adjusted so that there is a constant flow of escaping air, allowing the diver to stay on the bottom or suspended at a chosen depth.

A small hand-operated tap or spticock in line with the diver's mouth is sometimes incorporated in a standard diving helmet. It has two uses: to enable the diver to suck in a mouthful of water from outside the helmet with which they can wash down the inner side of the face plate if it has become fogged from the diver's breath; and as an auxilliary to the outlet valve in controlling the escaping air.

|

| Rotary air pump and box |

This is a low pressure rotary air pump used to supply air to hard hat divers. The machinery was fitted inside the wooden box, which in turn would have been located either inside a purpose built housing or simply on top of the deck of a smaller boat.

This is a three cylinder rotary air pump, and as the name suggests, it had to be turned in order for it to pump air. A large flywheel (now missing) was located on either side of the box, each having to be turned by the diver's tenders. Inside the box, these wheels turned the crankshaft onto which are fitted three piston rods. When the crankshaft was turned, these rods lifted the pistons up and down inside the piston cylinder.

In each cylinder, depending on whether the piston was up or down, air was either sucked in (piston up) or expelled (piston down). There was always a piston in neutral position midway through a cycle. Expelled air was forced into the manifold and from there it flowed into the outlet vlave and into the diver's hose. Three pistons ensured that there was always a smooth and unbroken air supply.

The hose entered the diver's helmet by way of a non-return valve and circulated freely around the diver's head. A non-return valve ensured that the air couldn't escape back up the hose in the event of the hose being damaged. The diver did not have any control over the flow of air and so had to signal the surface with specific pulls on his [sic] rope or airline to indicate that he needed more or less air. To accommodate this, the tenders had to alter the speed at which they were turning the wheel.

It all sounds quite ingenious and absolutely terrifying. What could possibly go wrong?

|

| Open style shallow water diving helmet |

There was lots of fascinating information and stories about diving pioneers, which I shall copy here, if only to remind myself to look them up later and as a record of their names and exploits.

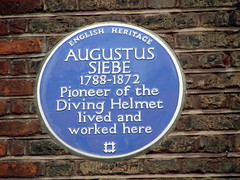

Augustus Siebe (1788-1887) was an inventor, engineer and manufacturer widely acclaimed as the 'father of diving'. Born in Saxony, Southern Prussia and educated in Berlin, Siebe served as a lieutenant in the Prussian army against Napoleon before immigrating to England in 1816. By 1819 he had established an engineering company and in 1828 Siebe produced a rotary water pump, which achieved public notice and financial success. he moved into 5 Denmark Street, London in 1830, which served as both his home and commercial premises.

After being approached by Charles and John Deane to turn their patented smoke helmet (for fire fighting) into a diving helmet, Siebe became interested in the development and manufacture of diving equipment. Based on the smoke helmet, he developed the first open diving helmet for Deane brothers in 1829 and by 1839 he had patented the first closed diving helmet.

Following experimentation and practical experience of salvage work through the clearnace of HMS Royal George where his closed diving suit was formally acknowledged as superior to all other available apparatus and recommended as admiralty standard, Siebe's company adverstised as 'submarine engineers' who could:

'Undertake all classes of Operations under Water, the Inspection of Works in Progress, Cleaning of the Bottoms of Vessels, the Recovery of Sunken Property, the Removal of Wrecks, Boring and Blasting of Rocks and Removal of same, Ship Raising, &c, &c.'

Some of Siebe's other inventions included a breech loading gun (1819), the dial weighing machine, a galvanic battery, and a paper-making machine. In 1850 he manufactured one of the first ever ice-making machines under license from an Australian, James Harrison.

Siebe was awarded medals at the 1851 Great Exhibition and the 1855 Paris Exhibition and was elected an Associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1856. He is still best remembered for the development of the closed dress diving dress which was successfully used in the the salvage of the Royal George.

In 1870 under the control of his son William Henry Siebe and his son-in-law, William Augustus Gorman, Siebe's business became known as the Siebe Gorman Company, famous for supplying diving equipment to navies and commercial operators throughout the world. Augustus Siebe died in 1872 of chronic bronchitis. In 2000 Siebe was honoured by the City of London with an English Heritage blue plaque at 5 Denmark Street, SOHO.

Melbourne 'Mel' Ward (1903-1966) was an actor, naturalist and marine collector, born in Melbourne and educated in Sydney and New York. He left school for a stint on the stage where he shone at acrobatic dancing and in pantomime routines. From childhood, Ward had been fascinated by the crabs he found on beaches; as a schoolboy he haunted the American Museum of Natural History. After a small red crab that he discovered in a Queensland beach was named (1926) Cleistostoma wardi after him, he abandoned the stage for marine biology.

His expertise in marine biology was honed over a number of trips to the Great Barrier Reef and Northern Australia, and by the late 1920s, he had collected not only in Australia, but also in Samoa, Fiji and Hawaii, along the Atlantic and Claifornian coasts of the U.S.A., and in Cuba, Panama and Mexico. While in Cuba, he famously drew on his acrobatic skills in a daring feat to snatch a species of crab that lived in quicksand. He pioneered the use of goggles and diving helmets amongst Australian marine scientists and was the subject of the first underwater photograph taken in the Great Barrier Reef, and found turtle riding 'a fascinating sport, as exciting as anything I know'.

Possessing independent means, in 1930-31 Ward embarked on a scientific 'Grand Tour': he worked with Dr Mary Rathbun at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, lectured at the British Museum, London, studied in museums in Berlin and Paris, and collected in the Mediterranean. In 1933 Ward and his wife (Halley Kate Foster) went to Lindeman Island on the Great Barrier Reef as entertainers, playing duets on the clarinet and guitar for tourists. They combed the reef at every low tide and Mel set up a museum and laboratory. He continued to collect for the Australian Museum throughout the 1930s, carried out research for the raffles Museum, Singapore, and the Mauritius Institute.

In 1929 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Zoological Society, London, and was appointed an honorary zoologist of the Australian Museum. Ward was made a life member of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales in 1947 and published in Australian and international scientific journals. Mel Ward died in 1966 in the Blue Mountains. His extensive natural history collections (including 25,000 crabs) were donated to the Australian Museum, Sydney.

|

| Some of the Mel Ward collection of crabs at The Australian Museum |

No comments:

Post a Comment