|

| Metal Construction 123 - Robert Klippel |

With a career spanning six decades, Robert Klippel was one of Australia's leading sculptors. His work investigates the realtionship between the organic and the mechanical; a duality that he saw as central to life and culture in the twentieth century. He took night-courses in arc-welding, silver soldering and panel-beating to acquire new skills.

In 1957 he moved to New York where he explored the unlimited 'vocabulary of shapes' available in junk metals. Using detritus - the chance fragments of modern disposable society - he created complex configurations with new life and meaning. By the late 1960s he had begun to shift his emphasis from using primarily machine parts to steel sections. Klippel aimed to synthesise sculpture and landscape and bring nature and technology together.

|

| Metal Construction 202 (1966) - Robert Klippel |

Angelina George paints the most amazing expansive canvases of her home land where she grew up and remembers when she used to walk about with her brothers and sisters or her mother. In the series of Dry Season paintings, she says she has worked from memories and imagination so it is 'not exactly what it looks like. You know. Traditional way and law.'

The sharp cliffs and rugged rocks hide billabongs and creeks where they find fish and birds. She says, 'we had to find our own tucker and we knew where to go hunting.' The spectacular landscape formations and shadows in these paintings are barren, bleak and beautiful with the sky forming only a tiny fraction of the canvas - the remainder is comprised of reds, oragnse, purples and distant greens. There is clearly life, if you know where to look.

|

| Untitled (2008) - Angelina George |

When Ben Quilty first asked legendary painter Margaret Olley to sit for him, she said no. 'Her lack of ego is so appealing. Margaret didn't understand why anyone would want to see a portrait of her.' Fortunately, she relented and this amazing portrait in which paint sticks out in great blobs and swathes to create a fantastically piercing expression, won the Archibald Prize in 2011.

|

| Margaret Olley (2011) - Ben Quilty |

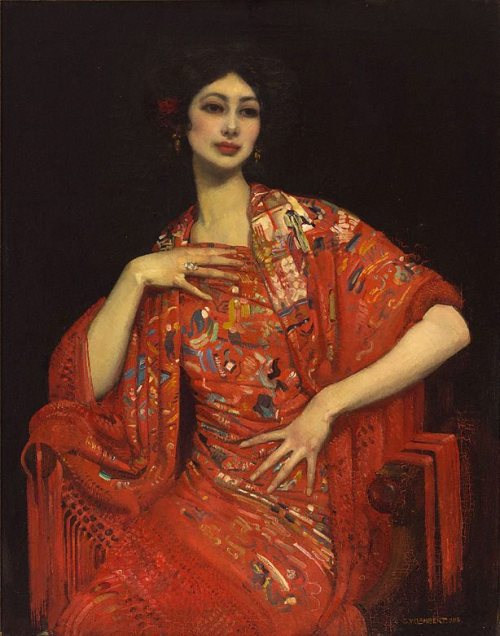

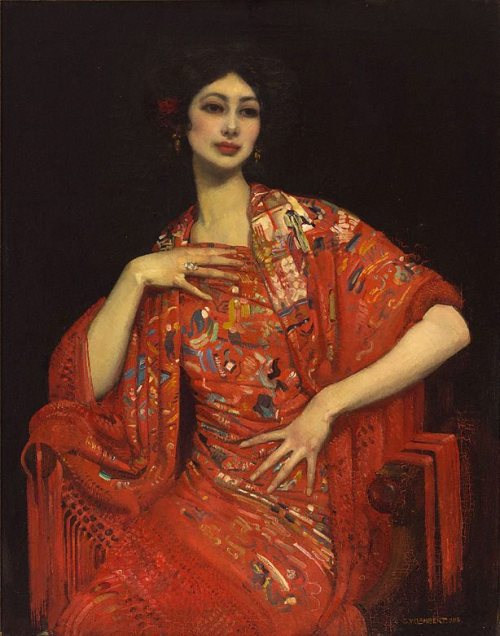

George Lambert's work is also a study in texture. In The Red Shawl, the material in its form and colour seem to be more important than the sitter. Another subject is caught in the act of removing her glove in Miss Helen Beauclerk and again, the detail paid to the fabric and the stitching of the material suggests the work of a fashion designer as much as a portrait painter.

|

| The Red Shawl (1913) - George W. Lambert |

|

| Miss Helen Beauclerk (1914) - George W. Lambert |

A third 'portrait' that caught my eye was Important People. Lambert suggested an allegory in his grouping of a flower-seller, a clerk and a boxer. He felt it should not only be the wealthy who get their portraits painted and that his work represented motherhood, the future generations, the fighting forces of the world and administrative qualities, without which the world (symbolised by the red cart wheel) would not turn smoothly.

|

| Important People (1914-21) - George W Lambert |

Eric Wilson studied abstract design and cubist philosophy on his travels to London and Paris. In Abstract- the kitchen stove he uses a domestic object to explore formal elements such as colour, shape, surfacing pattern and texture. The painting is structured around a triangular composition and demonstrates his attempt to create an 'orchestration of the formal elements into a symphonic whole'. The image also recalls domestic harmony in a musical instrument such as a lute or a cello.

|

| Abstract- the kitchen stove (1943) - Eric Wilson |

The cubist forms of the racehorse and riders in Weaver Hawkins' Going Round, create an almost stained-glass window effect. Hawkins was a founding member of the Contemporary Art Society and, in the early 1960s, a founding member of the Sydney printmakers' group.

|

| Going round (1954) - Weaver Hawkins |

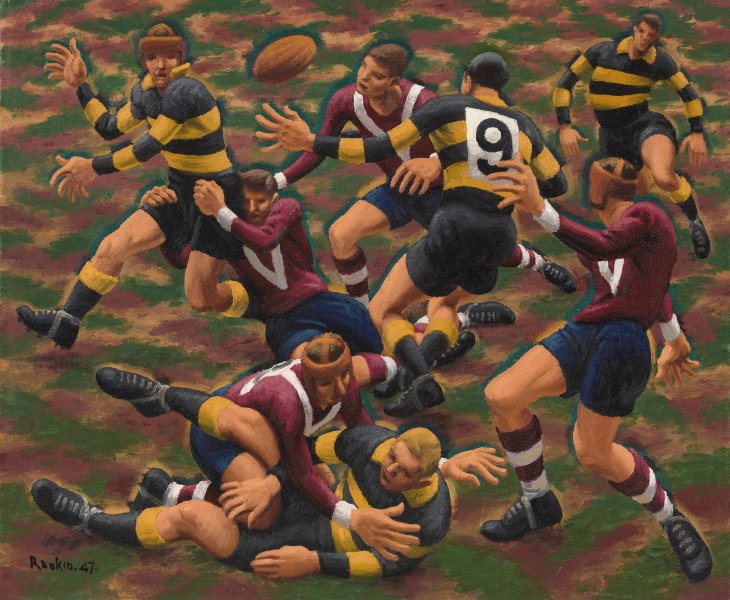

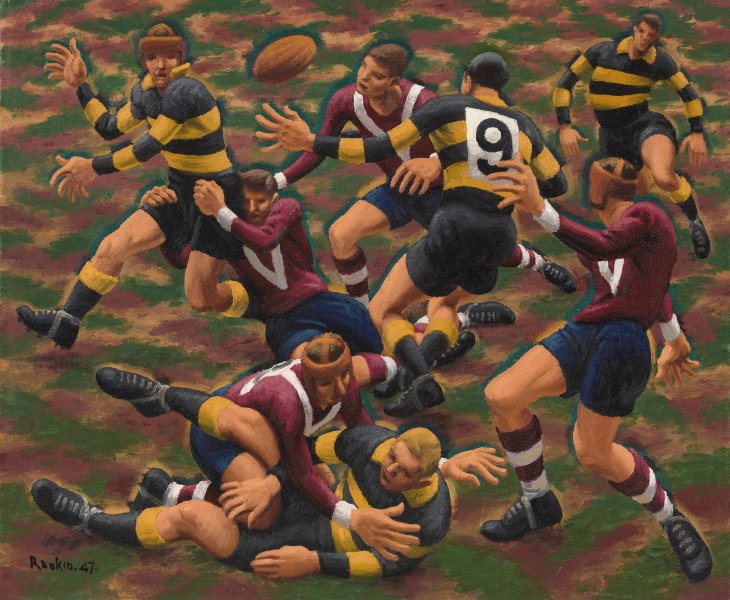

Hawkins' sporting works full of energy and movement assume another dimension when you realise that he was wounded in the Battle of the Somme and subsequently lost the use of his right hand and arm. He retrained himself to draw and paint using his left arm, which was never at full strength. From 1927 he began to use the alias 'Raokin' to avoid unwanted public and media perceptions about being an artist living with severe injuries after WWI. Almost as an antidote, the appreciation of the male form in all its rugged masculinity is on display in Dance of the Football Field, which depicts a rugby league match between Balmain and Manly.

|

| Dance of the football field (1947) - Weaver Hawkins |

No comments:

Post a Comment