- Description of a painting on Wikipedia: "Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856, it was described by the critic John Ruskin as 'the first instance of a perfectly painted twilight'. The painter's wife Effie wrote that he had intended to create a picture that was 'full of beauty and without a subject'. The picture depicts four girls in the twilight collecting and raking together fallen leaves in a garden. They are making a bonfire, but the fire itself is invisible, only smoke emerging from the between the leaves. The painting has been seen as one of the earliest influences on the development of the aesthetic movement." What is the name of the painting and the artist?

- Description of a TV series on IMDb: "The psychological thriller examines the lives of two hunters - one is a serial killer who prays on victims in and around Belfast, Northern Ireland, and the other is a female detective drafted from the London Metropolitan Police to catch him." What is the name of the TV series and the actors who play those characters?

- The first lines from the translation of a novel: "May I monsieur, offer my services without running the risk of intruding? I fear you may not be able to make yourself understood by the worthy ape who resides over the fate of this establishment. In fact, he speaks nothing but Dutch." What is the name of the novel and the author?

- Description of some music on Classic FM: "Like the other concertos [this] has three movements; the first is energetic and rhythmic, and depicts a harvest festival dance. The second is a slow movement that seems to usher the cool air and reflective crisp mornings well and truly in. And the third movement is a lively and jaunty affair, setting to music an autumn hunt taking place atop a layer of crispy settled leaves." What is the name of the concerto, the suite from which it is taken and the composer?

- Description of a film by Variety film critic Emanuel Levy in 2000: "Utterly banal, Joan Chen's tediously sappy romance is a kind of modern-day Love Story (a better film!) with a 'twist': Richard Gere's suave lover is old enough to be Winona Ryder's father." What is the name of the film?

Friday, 8 April 2022

Friday Five: Autumn Arts Part One

Tuesday, 5 April 2022

Espionage Isn't Always Exciting: The Spy Who Came in from the Co-Op

It should be

quite difficult to make such an exciting story sound so dull, and yet David

Burke manages it. While he is good at painting the big picture, he gets bogged

down in tedious detail too often. Melita Norwood was the last of the atomic

spies to be ‘run to ground’ in 1999, aged 87. She was deemed too old to

prosecute and there were protocols which prevented her questioning, but the

press had a field day, with headlines including the title of this book. Burke,

however, mainly concentrates on the history of espionage during the cold war

period, rather than her particular part in it, which seems like a missed

opportunity.

Melita Norwood

shared atomic secrets with Russia, which shortened the Soviet Union’s atomic

bomb project by about five years. As secretary for G.L. Bailey, Director of the

British Non-Ferrous Metals Research Association on the Tube Alloys project, she

had access to classified information, which she chose to share with Russia because

she believed in the Communist Party, but she also knew that if only one side

had the power, then the situation could be lethal.

Ursula Kuczynski

(Red Sonya) was Melita Norwood’s controller between 1941 and 1944, and the book

that Ben Macintyre wrote about her, Agent

Sonya: Lover, Mother, Soldier, Spy, was interesting enough to lead to this

one. In some respects, their spying trajectory was similar. As Burke writes,

her spying career had spanned two very different eras of Communism. “Here was a

woman who had spent her childhood among an eclectic mixture of anarchists,

suffragettes, Tolstoyans and the pioneers of British socialism, who had eagerly

embraced the ideals of Lenin’s October Revolution. Their Utopianism remained

with her throughout her life and blinded her to the worst excesses of

Stalinism.” Also familiar to anyone who has read the above book are the

descriptions of the ‘brush pass’ – the highly convoluted meetings between

operatives carrying explicit items in a specified hand – and the cover reasons

for the meetings, including vegetarian societies; football teams and

philatelists.

There was clear

evidence against Melita Norwood, but it was ignored “on a junior level” until

she was outed. It was still going on when Stella Rimmington, Director General

of MI5 had to answer questions about it in 1993. Many couldn’t believe that the

timid housewife could have nefarious motives. The Norwoods moved to Bexleyheath

in 1947, which was described as “the very epitome of post-war smugness in an

age of austerity, boasting houses with fake Tudor beams, spacious parks and

golf courses. It was middle country, middle class, middle management and

middlebrow.” This was something the authorities wished to cover up as their

focus was demanded elsewhere.

Friday, 18 March 2022

Friday Five: My Week in Theatre

- In Their Footsteps - Ashley Adelman and Infinite Variety Productions, Courtyard Studio: The blurb for this play reads, ‘Based on the true accounts of five extraordinary women, In Their Footsteps explores the experiences of women working in war zones, their struggles to be recognised heroes, their loss of faith, and the friendships they forget in the face of trauma. More than anything, it reminds us of the histories we hear… and importantly, the ones we don’t.’ The five women are engaging and sympathetic with their verbatim accounts of their service in different capacities from nursing to morale boosting (donut dollies) to intelligence work and librarians. Even though the accents are greatly variable (I'm pretty sure one of them isn't even trying), it is still poignant and powerful. We will remember them.

- Fly By Night - ANU Musical Theatre Collective, Kambri Drama Theatre: I’ve never even heard of it before, but, due to a friends' involvement, I went along to see it. The musical is set around the incident of the mass black-out on the northeast of the USA and Canada in 1965. The structure is based on a narrator who makes several false starts with the story and skips back and forth through time to tell the tale of a love triangle within a circular orbit. It's quite cute and charming and achingly self-aware with songs about becoming a star... or not. Of course I'm biased but my friend (Samuel Farr) was superb and his number, Cecily Smith, about how he met his dear departed wife is a highlight of the show. "Life is not the things that we do; it's who we're doing them with."

- Keating! - Queanbeyan Players, Belconnen Community Theatre: So, I don't particularly like musicals and I don't know a lot about Australian politics, having moved here in 2012 (all I knew about Paul Keating was that he 'inappropriately' touched the Queen in 1992), so I'm probably not the target market for this. But I loved it. Sarah Hull directs a deceptively simple character-driven cabaret-style show with each performer hitting all the right notes, and my goodness, I could even hear all the words, which is rare enough in a play these days, let alone a musical. From rock to rap, jazz to hip-hop and tango to calypso, the band plays to perfection and the genres and styles are all delivered with respect and ridicule in equal measure. Steven O'Mara oozes charisma and miasma as the titular role, and all the rest of the cast play the supporting and undermining ensemble with chutzpah and panache. This is bloody brilliant!

- Swansong - Canberra Theatre Centre, Courtyard Studio: Andre de Vanny delivers a powerful performance as Austin 'Occi' Byrne, the illegitimate child of a single mother in the Catholic west of 1960s Ireland. The one-man show draws the audience into his world of explosive emotion and violence. Written by Conor McDermottroe and directed by Greg Carroll, the drama reeks of misplaced testosterone. It is deeply uncomfortable as the audience is encouraged to side with Occi, a man who stalks and punches women, and callously commits murder because he doesn't like a name he is called. The brutal bravado is tempered with charm, humour, and severe undiagnosed mental health issues. Andre de Vanny is excellent at telling his story, but it's not one that should have any excuses.

- Ruthless! - Echo Theatre Company, The Q, Queanbeyan: What a delight to see a musical featuring six strong roles for women, who each get to shine and compete for the limelight. Eight-year-old Tina Denmark (Jessy Heath) has talent and she is desperate to use it. Her mother Judy (Jenna Roberts) is horrified when she discovers the lengths to which her daughter will go to secure a part in the school play (aided by talent-spotter Sylvia St. Croix played by Dee Farnell), until she discovers it's not just a part; it's the lead! Director Jordan Best brings out the high camp and stereotypical bitchiness of musical theatre performance in this dark comedy homage which is as fun as it is twisted. The vibrant set design by Ian Croker makes us feel like we're in a 1950/60s pop art/ TV sitcom, but there is nothing canned about this laughter. The vocals are stunning; the choreography humorously self-aware; the harmonies are on point; and the Bechdel Test is passed with flying colours.

- The Wider Earth - Dead Puppet Society, Trish Wadley Production and Glass Half Full Productions, The Playhouse: Charles Darwin's voyage of biological and self discovery aboard HMS Beagle (begun in 1831) is stunningly portrayed in this outstanding production. The ensemble cast moves the story and the scenery forward with aplomb as offices, ships, jungles and downs are conjured up with projections and simple on-stage effects. Finches, giant Galapagos tortoises, fireflies, butterflies, iguanas, turtles, sharks, shoals of fish and a scene-stealing armadillo are represented by skeleton puppets with incredible personality. Tom Conroy leads the cast as the young Charles Darwin full of questioning wonder and wrestling with the science and/or faith dichotomy which still continues to trouble civilization. This is a thoroughly engaging and immersive theatrical experience: highly recommended as a spectacle for all ages to enjoy.

|

| The Wider Earth |

Tuesday, 15 February 2022

Simply Exhausting: Olive Kitteridge

Writer

David Nicholls has described this Pulitzer-prize-winning book (in a quote

printed on the cover) as “An extraordinarily rich and detailed portrait of both

a marriage and a community.” And he’s right. Similar to Lake Woebegone Days or Fried

Green Tomatoes at the Whistlestop Café, it is the story of the village –

the inhabitants; the relationships; the gossip and the surprises – told in a

gentle, meandering style. But it is also nostalgic and elegiac in tone

(reminiscent of Eleanor Oliphant is

Completely Fine with focus on crucial social networks being actual rather

than just virtual, particularly in our post-lock-down world) while melancholy

and loneliness are achingly prominent.

Olive

is a retired schoolteacher, married to Henry, who used to be a pharmacist, and

with a strained relationship with her son who didn’t turn out to fit into the

mould she had made for him. Opinions range among the community, and people view

them differently. Olive is probably a Highly Sensitive Person, based on her

reaction to stimulus. She understands the needs and motivations of others although

when it comes to her own actions, she is not always so self-aware.

Set

in the town of Crosby, Maine, the landscape plays a Hardyesque part in the characters’

feelings and experiences. Autumnal colours are encouraging: “It was early

September and the maples were red at their tops; a few bright red leaves had

fallen onto the dirt road, perfect things, star-shaped.” Winter hues are not:

“The leaves were half-gone now. The Norway maples still hung on to their

yellow, but most of the orangey-red of the sugar maples had found their way to

the ground, leaving behind the stark branches that seemed to hang like

stuck-out arms and tiny fingers, skeletal and bleak.”

The

novel comprises thirteen short stories that are interrelated but discontinuous

in terms of narrative, although the community is everything to itself. Throughout

the community, the school and the church remain as focal points, which could be

considered both good and bad in a current climate. One character reads in the

newspaper, “They were making a film about the towers going down. It seemed to

him he should have some opinion about this, but he didn’t know what to think.

When had he stopped having opinions on things?” Among the stories, told in the

third person free-indirect style (where the language takes on the aspect of the

character), there is a funeral reception for adulterous husband, a

hostage-taking in a hospital, an anorexic girl spurned by her boyfriend, and an

alcoholic lounge pianist reeling from a toxic relationship. The inhabitants of

another house only go out at night to preserve their privacy after a family

tragedy.

Parochial

and insular, the novel is not about global events or political or social issues,

but personal battles with nostalgia and loneliness. One of the characters

connects music with memories of the past and realises, “She had never liked

music. It seemed to bring back all the shadows and aches of a lifetime.” Olive struggles

with an introverted/ extroverted personality familiar to many. “She didn’t like

to be alone. Even more, she didn’t like being with people.”

If

there is a message – and I’m not sure that there is – it is to cherish the

moment and be ‘present’ but not in a pumped-up-business-speak way. “Life was a

gift – one of those things about getting older was knowing that so many moments

weren’t just moments, they were gifts.” Olive knows that “loneliness can kill

people” and she divides her life into what she thinks of a ‘big bursts’ and

‘little bursts’, considering that one needs a balance of the two.

Friday, 4 February 2022

Friday Five: Films on a Plane

- Delicious - Well, it looks beautiful - shot to make the mouth water (cinematography by Jean-Marie Dreujou). Sacked by his master, the Duke of Chamfort (Benjamin Lavernhe), for showing too much initiative as a chef, Manceron (Grégory Gadebois), gets his own back by setting up France's first restaurant on the eve of the fall of the Bastille and proving that not all service is servitude. He is assisted by Louise (Isabelle Carré) who turns up with a desire to be his apprentice. There is obviously more to her motivation than that, and it transpires that freedom to cook your own recipes is a revolutionary act. The dastardly duke believes that food is only for the rich as they have the exclusive ability to appreciate it. Ideas of setting out individual tables with tablecloths, writing up a menu, using fresh produce and not drowning it in heavy sauce were new; revenge as a dish best served cold was not.

- The Green Knight - Green is the colour; denoting growth, renewal, mould and decay - it is cyclical and endless, like this legend. It's arty but beautiful with the perfect counterpoint of bleakness, and Dev Patel as Gawain is charming enough to carry the tale. One for the mythologists.

- Jungle Cruise - I watched it on a plane, and it was good, mindless fun. The plot is negligible and the acting is all admirably sound with Emily and Dwayne being highly reliable as the wholesome adventurous duo. Jack Whitehall, Jesse Plemons and Paul Giamatti are totally predictable as the camp brother, Teutonic baddie and avaricious business-owner respectively. If you want to watch a movie (and it is a movie rather than a film) based on a theme park ride; you pay your money and you get exactly what you order.

- Last Night in Soho - The multi-genre format of this film is what makes it so intriguing. It's part thriller; part horror; part social commentary; part fantasy/ sci-fi and part period drama. A young woman, Eloise (Thomasin McKenzie) leaves her safe rural home to study fashion design in London because the lights are much brighter there. We learn that her grandmother worries about her mental health (her mother took her own life) and fears she might be out of her depth. With her fertile imagination, Eloise conjures up a world of SoHo in the swinging sixties where she believes all is glamorous, as epitomised by the characters of Sandy (Anna Taylor-Joy) and Jack (Matt Smith). As this fantasy world becomes more real, however, she discovers the seedy underside of the city where everyone is being exploited and love is never free. The ending may be a touch outré, but the film is definitely watchable and gripping, portraying the capital as a palimpsest of buried secrets.

- My Son - It feels as though this was filmed during lock-down, with minimal sets, locations and cast. James McAvoy and Claire Foy are an estranged couple who have to communicate when their son goes missing form a holiday camp in Scotland (the scenery is spectacular). We soon suspect he has been kidnapped, but why, by whom and, most importantly, is he still alive? These two are great actors but the plot is really weak and sketchy. Apparently this is a remake of a 2017 French thriller, Mon Garçon, and the director (Christian Carion) both times requested that his lead actor perform without a script. James McAvoy is brilliant but he is an actor, and they tend to deliver lines. Without any, this by necessity falls down into a fairly pedestrian narrative, which seems a shame and a shocking waste of opportunity.

- Spencer - Was the point of this film to reinforce the perception that Diana was a selfish, manipulative self-indulgent attention seeker? If so; job well done. With little consideration for anyone but herself (including her children), she sets out to make the traditional Christmas all about her by flouting the family like a spoilt child who suddenly realises she is not getting her own way at every opportunity. This would not be interesting if the family were not royal and she were not the vomit-inducing (yes, she does a lot of that) 'queen of hearts'. Kristen Stewart gives a credible performance as a portrait of a victim, but the whining is deafening and the sympathy short. Plaudits to the costumiers and the design team - the rest is overwrought hokum. Americans will love it.

Wednesday, 26 January 2022

Colouring in between the lines: Stanley and Elsie

Never read about your heroes. Sir

Stanley Spencer may have been a brilliant and talented painter who created

works of magnificence, but it seems he was a very selfish and unpleasant

individual. His life, like his artwork, was unconventional and would have been

described at the time as Bohemian. At the time of the novel he is married to

Hilda (Carline) and they have two children, but he has an affair with a woman with whom

he thinks he shares a background, Patricia Preece. Patricia is in a relationship

with Dorothy Hepworth, which continues throughout her affair with Spencer. He divorces

Hilda and marries Patricia, who continues to live with Dorothy, and Stanley

returns to Hilda whom he cares for through cancer until her death. These are

facts and, therefore, not spoilers.

|

| Dorothy Hepworth, Patricia Preece, Stanley Spencer and Jas Wood at the wedding of Preece and Spencer (1937) |

The novel is narrated by Elsie,

who was the housekeeper and, at times, confidant to both Stanley and Hilda, and

she learns about and talks to the man in a manner that suggests her position is

obscure. She wonders how deeply to involve herself in the lives of these

people, about whom her parents have warned her, because artists are all a bit

odd. She claims to not want to cause difficulties, and yet she is keen to be a

part of the relationship. When Stanley paints her and calls the painting Country Girl, she is offended that he

sees her as a simple village girl, but he counters the painting is of “the girl

I’ve watched so closely, the girl whose neck I love, whose mouth, whose legs,

whose whole demeanour – not because I love them,

but because I love her. I called the

painting Country Girl because it

celebrates everything you and I have in common.” This is definitely not fact

but overt fiction. Supposedly the novel is more about Elsie than his wives,

Hilda and Patricia, but although Elsie narrates, we don’t learn much about her.

Maybe she just isn’t a very interesting character.

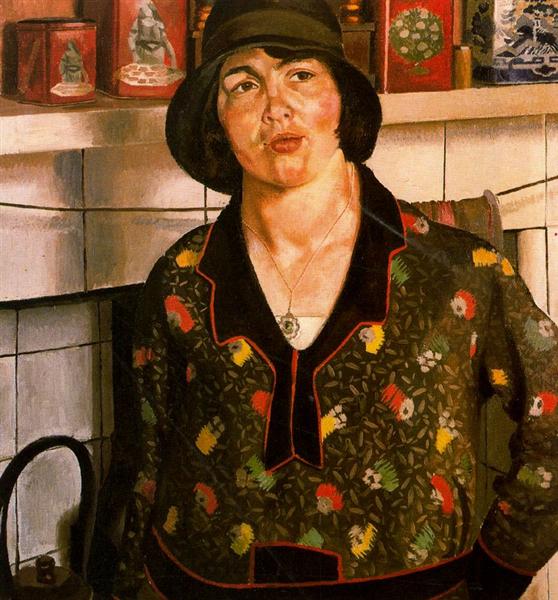

|

| Country Girl by Stanley Spencer (1929) |

Stanley makes all the women in

his life desperately unhappy, but Patricia seems to want him for his networks

and his introductions to galleries. She is very glamorous, but not as good a

painter as Dorothy, whose works she passes off as her own (with Dorothy’s

consent). After the breakdown of Stanley and Hilda’s marriage, Patricia wonders

whether to marry him or not, knowing she will be damned either way. “I’d rather

be a money-grabbing bitch than a penniless whore.” Dorothy warns her, “People

will take Stanley’s side. He has a talent for rousing sympathy, and the man is

never at fault when there’s a woman to blame.”

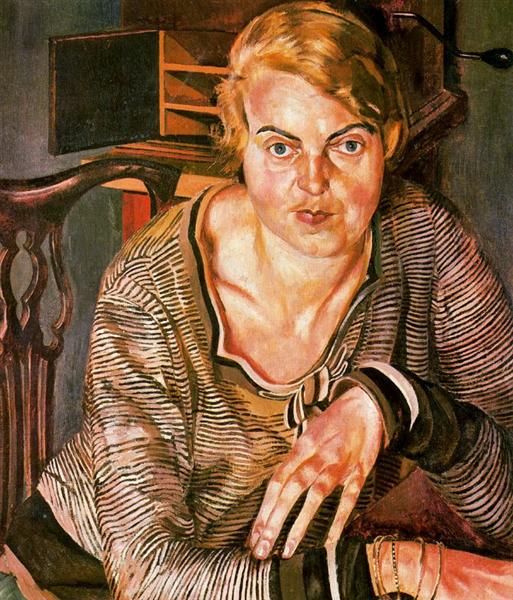

|

| Portrait of Patricia Preece (1933) by Stanley Spencer |

Hilda loves the garden and

growing things; it is holistic and she is skilled at it, although Spencer

dismisses it. On one occasion she brings in some snowdrops from the garden and

when Patricia visits with some exotic blooms she has bought, he dumps the

snowdrops out of the vase to replace them with the showy blooms, in an

obviously symbolic gesture. Metaphors are stretched a bit thin to cover Stanley’s

attitude to relationships and other people, as Hilda tells him, “Life’s one big

picture as far as you’re concerned. You put yourself at the centre of it and

paint the rest of us around you, hoping we’ll stay where you want us to. But

real people are different. Real people live and breathe and change, and not

only at the stroke of a brush.”

|

| Hilda with Bluebells (1955) by Stanley Spencer |

Spencer was skilled at organising multi-figure compositions such as in his large paintings for the Sandham Memorial Chapel, dedicated to the fallen of the First World War. He himself suffered from PTSD after the war, and tried to highlight and celebrate the mundanity of the army, including figures of men washing uniforms, cleaning tackle, studying maps, eating breakfast or making tea in his images. Spencer also has a complicated relationship with religion and, besides painting the artwork for the chapel, he paints Jesus into many of his pictures, often doing simple tasks as one of a group, not as the principle figure in the image, but as one of the crowd. He keeps a copy of St Augustine’s Confessions by his side while at work as inspiration. “There’s a passage about serving God through ordinary things. ‘Ever busy, yet ever at rest. Gathering yet never needing, bearing, filling, guarding, creating, nourishing, perfecting, seeking though thou hast no lack.’ As soon as I read that, I knew why I was there. It was all a service to God, even if I wasn’t fighting.”

|

| Paintings at Sandham Memorial Chapel |

Through his art, Spencer is intrinsically linked to Cookham, the village on the River Thames where he was born and spent many years of his life. He referred to Cookham as ‘a village in heaven’ and in his biblical scenes, fellow-villagers are shown as their Gospel counterparts, expressing both his unconventional faith and the compassion that he felt for his fellow residents. I know the area well, and I can picture the streets Nicola Upson writes about in the novel, and the train journey into London, which Elsie takes when visiting Patricia in the city.

|

| Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta: Dinner on the Hotel Lawn (1957) by Stanley Spencer |