Thursday, 17 October 2013

Shining Example

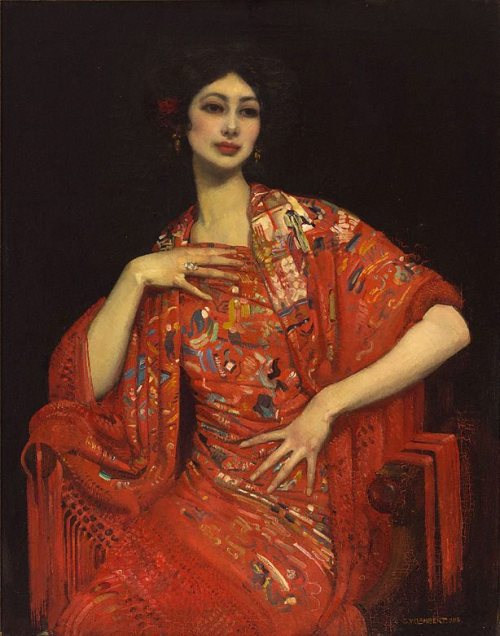

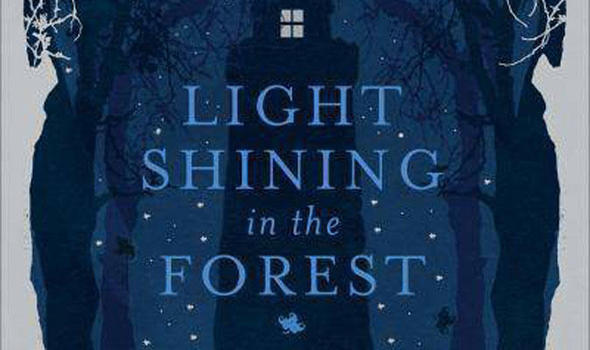

Light Shining in the Forest by Paul Torday

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $29.99

Pp. 350

Every five minutes a child goes missing in the UK. This bald fact is reiterated throughout this novel, which deals with absent children, presumed runaways or victims of kidnapping. And yet it is not a police procedural.

Geordie is a logger working alone in the forest. His relationship with Mary is collapsing and his mind strays since the unexplained disappearance of their son, Theo. The overtones of the kindly woodcutter are strong and the presence of the trees becomes ominous like those in a pop-up storybook. “The trees are there because the trees are there.” If this is a fairytale it is more Brothers Grimm than Disney.

Another of the missing children, Becky, has an alcoholic mother and a distressed home life. A third, Karen, is comfortable and well-looked after. There doesn’t seem to be any pattern, but they all like to read. As in the best psychological thrillers, the familiar is rendered frightening, such as the mobile library van with its ice-cream chime luring children onto the street like a Pied Piper. But this is not a horror story.

Pompous politician, Norman Stokoe is newly appointed to the position of Children’s Czar for the North East. He isn’t sure what this entails but he sits behind a desk, patronises his secretary, Pippa, drinks a lot of coffee, and attends meetings. Although he doesn’t like children – “Children cost money. They take up time. They disrupt one’s routine” – he knows all the statistics about their welfare or lack thereof. “It is an industrial scale problem and it requires an industrial response. The UK leads the world – but whether in measuring the problem or solving it, it is harder to say.” There is a major discrepancy between the emotional and the objective, but this is not a sociological treatise.

An intrepid reporter, Willie Craig, stumbles across a potential story in the missing children and brings it to Norman’s attention. Willie finds life on the local paper in rural Nothumberland crushingly dull and is at loggerheads with his editor who believes that “a local newspaper should concentrate on community issues and leave the rest to the national tabloids.” There are elements of detection and deduction, yet the main focus is not on investigative journalism.

Paul Torday wrote the book-club favourite Salmon Fishing in the Yemen, made into a shiny film starring British box-office darlings Emily Blunt and Ewan McGregor, and criticised by some for being a little bit twee. Some of those capricious characteristics emerge in this novel. It is written entirely in the present tense with a refreshing lack of adverbs and attributions, and with undertones of humour implicit in the short, breathless sentences: “She listens. She is rapt, like a raptor.” But this is far from a quirky flight of whimsy.

In fact, it is hard to pin down exactly what this novel is, which is, obviously, the point. In this age of sound-bite culture, we like to pigeonhole and opine in definitive terms. Whereas previous ages looked to the supernatural to interpret things they couldn’t understand, we prefer scientific rationalisation while we worship celebrities. A crucifix hanging on a wall is deemed unusual. “It’s where most people Willie knows would have pinned up Newcastle Untied colours. In his own flat he’s got a shirt signed by Alan Shearer pinned to the wall as decoration. No crucifixes.”

And yet what possible logical explanation can there be for what we do to our children? “Look at the headlines in the papers most weeks: children are tortured as witches; they are tortured for recreational purposes; they are abandoned, abused, trafficked, exploited, or just lost.” Torday hints of something spiritual in the disappearance of the children, from the Angel of the North statue, which Norman spots on his drive up to Newcastle, “spreading its protective wings above the warehouses and factory units below”, to the shadows of the wind turbines, “like a cross over the road”, and the light shining in the forest, which startles Geordie as he lumbers there.

Although “Nobody wants to accept that the unreal can become real”, Theo displays stigmata – the physical representation of Christ’s wounds on the cross – which the authorities suspect are marks of abuse. When Torday invents a genuine Deus ex Machina, Pippa reflects, “there doesn’t seem to be much of a market for miracles these days”, but it is no more unbelievable than the horrific alternative of a person who plays God by taking and creating life.

Not all questions the novel poses are neatly answered, which can be frustrating if you like your stories to have tidy endings. The world may be “rather annoyed by something that it cannot easily explain”, but by not supplying pat explanations Torday’s latest novel remains mystical and tantalising. And due to a masterful control of tone, pace and suspense, in the hands of a sensitive director, it will make an excellent film.

Wednesday, 16 October 2013

Getting cocky

If you’ve ever wondered who

Would win in a fight

Between a sulphur-crested cockatoo

And a trio of Bratz dolls,

I could tell you.

On the roof

Are three mini macabre mannequins

With tatty clothes and tangled hair

Tossed there by the girls next door

Who find it hard to differentiate

Between torture and play;

Sugar and spice.

The cockatoo attacks;

It holds the dolls with a gripping claw,

Gouges their vacuous eyes,

And tears off their heads with

Its creatively curved beak.

Darwin’s design never envisaged

Such scenes of savagery.

The pompous image is punctured;

The tarnished attire is tattered;

The big-headed idols are vanquished.

A victory for the sulphur-crested suffragette

As she rips apart the ridiculous facade,

Exposing the ‘reclaim your inner slut’ mantra

As offensive, puerile hokum.

But the bird is a boy

And the violence feeds baser needs.

Some would say they asked for it,

Dressed like that.

Labels:

doll,

feminism,

poem,

sulphur-crested cockatoo

Friday, 11 October 2013

Friday Five: Cheap as chicken

I like chicken as much as the next person. Or at least, I thought I did, until I moved to Australia, where it seems that the average person likes chicken a lot.

Australia has the second highest number of sheep in the world (after China) and yet lamb is quite expensive here. Australia is the seventh largest cattle rearing country in the world, but beef is still pretty pricey. Australia doesn't even make the top ten of national poultry producers, but chicken seems to be the choice meat of the country. This extends to the number of 'fast food chicken restaurants', of which there are many, without even resorting to the globally ubiquitous KFC.

5 Fast-Food Chicken Outlets in Australia:

Australia has the second highest number of sheep in the world (after China) and yet lamb is quite expensive here. Australia is the seventh largest cattle rearing country in the world, but beef is still pretty pricey. Australia doesn't even make the top ten of national poultry producers, but chicken seems to be the choice meat of the country. This extends to the number of 'fast food chicken restaurants', of which there are many, without even resorting to the globally ubiquitous KFC.

5 Fast-Food Chicken Outlets in Australia:

- Nando's: originally South African, but it has been in Australia for the past 15 years.

- Red Rooster: first opened in Kelmscott, WA, this is now 'Australia's largest roast chicken operation'

- County Chicken: 'crisp and light with a taste just right', they also fry other stuff besides chicken, like fish.

- Henny Penny: mainly in NSW they describe themselves as 'quick service' rather than 'fast food' restaurants.

- Kingsley's Chicken: 'unbelievable value; awesome chips' apparently - they are a Canberra and Queenbeyan 'speciality'

Thursday, 10 October 2013

Australian Galleries 3

With a career spanning six decades, Robert Klippel was one of Australia's leading sculptors. His work investigates the realtionship between the organic and the mechanical; a duality that he saw as central to life and culture in the twentieth century. He took night-courses in arc-welding, silver soldering and panel-beating to acquire new skills.

|

| Metal Construction 202 (1966) - Robert Klippel |

The sharp cliffs and rugged rocks hide billabongs and creeks where they find fish and birds. She says, 'we had to find our own tucker and we knew where to go hunting.' The spectacular landscape formations and shadows in these paintings are barren, bleak and beautiful with the sky forming only a tiny fraction of the canvas - the remainder is comprised of reds, oragnse, purples and distant greens. There is clearly life, if you know where to look.

|

| Untitled (2008) - Angelina George |

|

| Margaret Olley (2011) - Ben Quilty |

|

| The Red Shawl (1913) - George W. Lambert |

|

| Miss Helen Beauclerk (1914) - George W. Lambert |

|

| Important People (1914-21) - George W Lambert |

|

| Abstract- the kitchen stove (1943) - Eric Wilson |

|

| Going round (1954) - Weaver Hawkins |

|

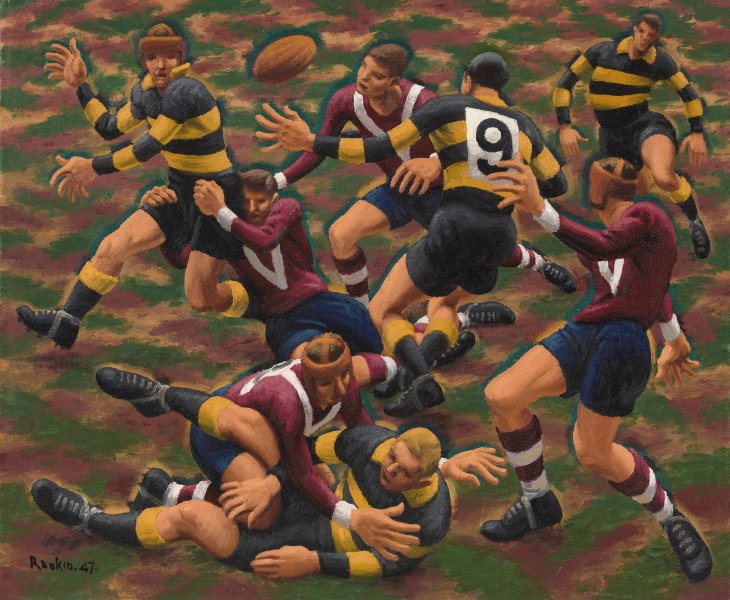

| Dance of the football field (1947) - Weaver Hawkins |

Wednesday, 9 October 2013

Australian Galleries 2

According to visitor feedback, this is the ‘most-loved Australian landscape painting’ in the gallery. Elioth Gruner painted it in 1919 en plein air at Emu Plains. The cattle breath and morning shadows reaching out to the viewer, hark back to a rural nostalgia which was rapidly disappearing. The vigorous foreground brushwork and the sense of light and tone create a wistful world worth fighting for.

I also like his later work, which is more severe in form and outline. By emphasising the subtle harmonies of tone and colour, he creates a feeling of stability and permanence in contrast to his former exploratons into the evanescence of light. These organised pictures are more scientific and less emotional, but the landscape is familiar to me, with the sweep of hills to the valley river corridor, being the view from the back of our house.

|

| On the Murrumbidgee (1929) - Elioth Gruner |

This particular portrait was painted in her father's studio (which we have visited), with the Vermeer prints on the walls. Nora wrote, "I greatly admired Vermeer’s works and wanted to paint like him – perhaps Vermeer and my father were my biggest influences in those days …"

|

| Self Portrait (1932) - Nora Heysen |

|

| Summer (1915) - Margaret Preston |

"Her engaging play with reflections, a device she returned to throguhout her long painting career, shows another landscape mirrored in the teapot. A hammock of pink cradles a solitary figure in a long dress holding a parasol ad standing in a green field with a blue sky, so introducing a human element to the painting's design. The figure could be the viewer or a partaker returning to the afternoon tea."

|

| Still life with daisies and teapot (1915) - Margaret Preston |

|

| Flowers (1922) - Margaret Preston |

|

| Australian gum blossom (1928) - Margaret Preston |

|

| The Proctor's tea party (1924) - Margaret Preston |

The restricted palette and strict analysis of form in this painting reveal how she turns to the genre of still life to express her conceptual conflict. The domestic vessels have been renamed 'implements' and reduced to essential forms.

|

| Implement Blue (1927) - Margaret Preston |

|

| Self Portrait (1930) - Margaret Preston |

The subject of the painting is Madge, the artist’s sister, knitting socks for soldiers serving on the frontline in World War I. Distinctly modern in its outlook, The sock knitter counterpoints the usual narratives of masculine heroism in wartime by focusing instead on the quiet steady efforts of the woman at home.

|

| The sock knitter (1915) - Grace Cossington-Smith |

|

| The Prince (1920) - Grace Cossington-Smith |

Reinforcements, troops marching (1917) - Grace Cossington-Smith

Inspired by the art deco designs and vivid colours of the David Jones department store cafe in Sydney, The Lacquer Room embodies the modern inter-war urban experience. The rich red and scattered patterns of the chairs are contrasted with the gleaming green of the lacquered tables, set against the brightness of the walls and polished floors. Grace Cossington Smith’s bold approach to colour exudes a sense of celebrating the new, similar to the contemporary consumer culture epitomised by the department store.

In an interview, she said, "It was quite a surprise, I didn't know it was there, but I went down to get cup of tea … and found this lovely restaurant … I was struck by its colour and general design the moment I saw it … Scarlet, green and white held me spellbound..."

|

| The Lacquer Room (1935-36) - Grace Cossington-Smith |

After Fox’s death in 1915, Carrick lived mostly abroad, travelling in Europe, painting in Majorca, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and India, and in the 1930s living in Kashmir. Her paintings commonly displayed an interest in figures, objects and her surrounding environment, rendered as patterns of colour and light.

|

| Flower Market, Nice (1926) - Ethel Carrick |

Tuesday, 8 October 2013

Australian Galleries 1

"Painting is an argument between what it looks like and what it means" - Brett WhiteleyHaving been confounded by contemporary art in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, I reassured myself with work that I actually like. Each time I come to Australian art galleries I familiarise myself more with local artists, themes and styles. I have just included in this post some of my favourites.

Whiteley's return to Australia in 1969 heralded a new preoccupation with colour and beauty. Inspired principally by Matisse, but also by his house at Lavender Bay on Sydney Harbour's north shore, he created a series of large scale paintings of expansive interiors and views evoking the marine beauty of the harbour. I like this expansive blue canvas dotted with boats and the faint white line-drawing of the bridge.

|

| The Balcony 2 (1975) by Brett Whiteley |

"Five bells was my first commission to paint in situ to cover a wall … I didn’t hesitate. I brushed a line around the core theme, the seed-burst, the life-burst, the sea-harbour, the source of life. Inside and around this core, I painted images drawn from metaphors and similes in [Kenneth] Slessor’s poem of our harbour city, and from my own emotional and physical involvement with the harbour, and with my young family in Watsons Bay …I wanted to show the Harbour as a movement, a sea suck, and the sound of the water as though I am part of the sea ... The painting says directly what I wanted to say: ‘I am in the sea-harbour, and the sea-harbour is in me’." - John Olsen

|

| Five bells (1963) - John Olsen |

John Brack uses repeated angular forms for his painting of a woman mid-conversation. Communication is usually a positive thing but in this sepia tinted rendition it is strained and isolating. The viewer, positioned as a direct and close observer, is drawn into the stark geometry of the composition.

|

| The Telephone Box (1954) by John Brack |

|

| Nebuchadnezzar on fire falling over a waterfall (1966-68) by Arthur Boyd |

|

| Hare in Trap (1946) - Sidney Nolan |

|

| First-class marksman (1946) - Sidney Nolan |

|

| Apocalyptic horse (1956) - Albert Tucker |

|

| Faun attacked by parrot 3 (1968) - Albert Tucker |

Labels:

Albert Tucker,

Arthur Boyd,

Brett Whiteley,

John Brack,

John Olsen,

Sidney Nolan

Sunday, 6 October 2013

Quote for today: And the point is...

|

| Reading Aloud - Julius LeBlanc Stewart |

"The point of a story is that it is that, a story, not a tract developing a moral. It is itself and it tells you." - Marion Halligan, The Apricot Colonel

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)