Ensemble Theatre Production

Street Theatre, 7-11 May 2013

From the opening strains of the cello (composer Elena Kats-Chernin; cellist Heather Stratfold), which set the tempo and the heart racing, and underscore the rest of the action, this visceral, chilling, moving and powerful drama (director Mark Kilmurry) provides much to look at and even more to think about.

Everyone knows a version of the Frankenstein story, but they are probably more familiar with the cinematic depictions of the mid 1900s than the psychologically tortured Gothic melodrama that Mary Shelley wrote in 1817. Despite a reference to the Hammer House of Horror in the predominantly black and white costumes with occasional splashes of red, Nick Dear’s adaptation focuses mainly on the ethical elements of the legend.

Having tinkered with the divine right of creation by constructing a creature from dead human skin and organs, Doctor Victor Frankenstein (Andrew Henry) must suffer consequences. If one wants to create life; one should produce children, yet Frankenstein’s reluctance for intimacy with his finance, Elisabeth (Katie Fitchett) makes this seem unlikely.

Instead he manufactures the Creature, which is represented with startling brilliance by Lee Jones. Jones’ spasmodic movements suggest a twisted choreography. The ‘birth’ scene in particular is incredibly disturbing: actions such as discovering one’s fingers, toes and penis, while cute in a baby, are confronting in a nearly-naked adult.

When thrown out by his disgusted creator, the Creature stumbles upon the farm of a blind university professor (Michael Ross), who teaches him morals, literature and philosophy, unafraid of what he can’t see. He explains that society can breed cruelty; people gather together for comfort and companionship, but then massacre each other, just as soldiers destroyed the professor’s books.

The professor’s son and daughter-in-law (Michael Rebetzke and Olivia Stambouliah) share a loving marriage. The Creature is inspired by this example of equality but when he is introduced to them they recoil in horror and he seeks revenge for their repulsion. Although he wants to be good and loved, he is scorned and derided, which forms his character.

Shelley was greatly inspired by the contemporary doctrine of Calvinism – Calvin taught in Geneva where much of the novel (and subsequently play) is set – which teaches that people are born depraved and only achieve salvation through God. Other religions and philosophies of the time propounded that we are born pure, and learn evil through education and environment. The entire novel can be read as a debate on this issue, and Kilmurry’s direction certainly highlights this aspect.

Things in nature go together and need partners, so the Creature needs a companion and asks Victor for a wife. It is a concept familiar to the Shelley’s and forms the essence of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem Love’s Philosophy; “The fountains mingle with the river/ And the rivers with the ocean/ The winds of heaven mix for ever/ With a sweet emotion;/ Nothing in the world is single,/ All things by a law divine/ In one another’s being mingle –/ Why not I with thine?”

The bride that Victor creates is ‘perfection’ by early nineteenth-century standards of the ideal female: she looks great but doesn’t say anything. Women were considered second-rate and early feminist principles are prevalent in Frankenstein (many male detractors argued that Mary Shelley couldn’t possibly have written such a great work herself and must have had help from her husband).

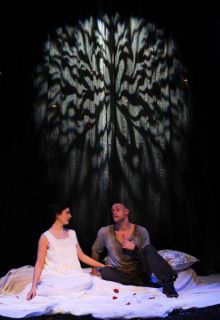

The bride that Victor creates is ‘perfection’ by early nineteenth-century standards of the ideal female: she looks great but doesn’t say anything. Women were considered second-rate and early feminist principles are prevalent in Frankenstein (many male detractors argued that Mary Shelley couldn’t possibly have written such a great work herself and must have had help from her husband). The handsome but austere settings of Switzerland and the North Pole wind and snowscape (with a brief foray to the Orkney Islands) are superbly executed through sound (Daryl Wallis) and lighting (Nicholas Higgins). Victorian light bulbs drip from the ceiling like stalactites, and the effects are exceptional from the pulsing accompaniment of the heartbeat to the flickering fire and woodland gobos.

The on-stage Foley art adds a nightmarish abstract dimension as actors recreate the sounds of grave digging, beatings and crackling flames. This enhances the clear and creative set design with a central scrim – the semi-transparent curtain occasionally closed like a hospital cubicle to screen the action while conversely highlighting dire imaginings.

The antagonistic symbiotic relationship shared by the Creature and his creator is made flesh by the spectacular acting of the principals and the co-ordinated cyclical design (Simone Romanuk). The final tableau of the North Pole connects us back to the beginning with its infinite succession of life, death, birth, creation and destruction; all reflected in the round black granite stage. It’s timeless, it’s brilliant and it’s truer to the original source material than any previous version of this classic tale.

No comments:

Post a Comment