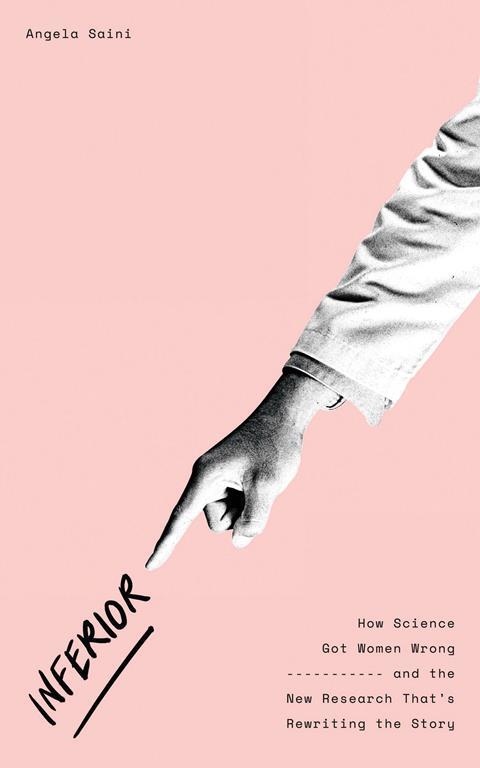

Inferior by Angela Saini

4th Estate

Pp. 237

Angela Saini contends that the so-called science which has labelled

women as ‘the weaker sex’ is biased and influenced by politics, history, and

social culture. Sick of people (men) telling her that women are inferior to men

based on dubious scientific data, she wrote this book in an attempt, “not to

lose control but to have at hand some hard facts and a history to explain

them”. She challenges myths and provides explanations as to why some

assumptions were made in the first place. Even though science is perceived to

be neutral, women have historically been excluded from research, experiments,

and theories. “Women are so grossly under-represented in modern science

because, for most of history, they have been treated as intellectual inferiors

and deliberately excluded from it.”

Darwin in his The Descent of Man believed that women were

inferior because he couldn’t see any women doing the same intellectual things.

“The evidence appeared to be all around him. Leading writers, artists and

scientists were almost all men. He assumed that this inequality reflected a biological

fact.” In evolutionary terms, drawing assumptions about women’s abilities from

the way they happened to be treated by society at the moment is narrow-minded

and dangerous.

Those ‘Men are from Mars; Women from Venus’ type ‘theories’ remain

popular because anything that claims to explore sex differences is highly

sought-after by media outlets looking for clickbait articles. People who counter

that differences are not wholly due to genetics are often labelled sex

difference deniers, in a way that would never be introduced in debates about race

or colour; not since the 1950s, anyway. Sexual selection theories which were

proven to be incorrect and unscientific, however, are making a popular

comeback.

People are messy and come with preconceptions and prejudices. Saini

argues that it is impossible not to politicise scientific data and that neuroscience

has profound repercussions for how people see themselves. Humans are bound to

pick up attitudes and adopt behaviours based on societal expectations rather

than independent biological factors or sex chromosomes. We are also able to

change and adapt as recent research into neuroplasticity confirms that the

brain isn’t set in stone in childhood but is in fact mouldable throughout life.

Saini also debunks several myths, such as the one that women are better

at multi-tasking than men. The paper that was published on this subject,

actually never reported this claim, but the cultural and gender stereotypes

were stressed in the press release. A further belief is that in previous

cultures men went hunting while women gathered, making the males dominant.

Research by Bion Griffin and Agnes Estioko-Griffin into the Nanadukan Agta

refutes this assumption, suggesting that males did some tasks and females did

others. “By and large people did whatever they wanted to do. There was no

sphere of work that was exclusively male or female – except perhaps the killing

of other people. Women would stay back

when groups of men went out on raids of their enemies”.

Hunting was not the primary source of nutrition anyway, so the group

that hunted did not have the most crucial task. While studying the !Kung

hunter-gatherers in southern Africa in 1979, Richard Borshay Lee noted that women’s

gathering provided as much as two-thirds of food in the group’s diet, so gathering

was arguably a more important source of calories than hunting. It is also

likely that the first tools were digging sticks and containers for the food, which,

being made from wood, skin or fibre, would break down and disappear over time

leaving no record, unlike the hard-wearing

stone tools that archaeologists have assumed were used for hunting. “This is

one reason that women’s invention, and consequently women themselves, have been

neglected by evolutionary researchers.” Many of these myths began

because they fitted the dominant – male – narrative that positioned women as

inferior.

Humans are not automatically the same as other animals, and much of our

behaviour is more likely due to societal pressure than biological expression. Women

are not inferior, and the science that seeks to suggest this is the case is

inevitably flawed. It is time for this to be recognised and stopped. Sarah Hrdy

argues, “A feminist is just someone who advocates for equal opportunities for

both sexes. In other words, it’s being democratic. And we’re all feminists, or

you should be ashamed not to be.” This is the science we should all follow.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/49546171/ChxnUSdWsAAr4sT.jpg-large.0.0.jpeg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/boaty-mcboatface-2000-1c651a8686274a06b533c44bc57aa6a9.jpg)